Cast your dreamhouse to the wind

Adwait Singh on Areez Katki’s exhibition As this chin melts on your knee, on view at TARQ Mumbai through 24 February 2024.

Commissioned by TARQ on the occasion of the exhibition.

Areez Katki, As this chin melts on your knee. Installation view, TARQ Mumbai

I remember when you first shared these dreams with me. I had just bookmarked an evening filled with Turkish roses, Kurdish songs, and improvised poetry. And as if this wasn’t enough to prime one for love, someone threw into the mehfil a serenade. A serenade! Blessedly delivered in a language twice removed from my own, it was veiled enough to allow me a graceful reception. And while my cheeks were still flushed from this unexpected honour I was pulled aside by my serenader and presented with an invite to his wedding. The next morning when I upended my confusion before M, his caffeine-craved face broke into helpless laughter. Like an azan breaking into the azure bivouacking the sea of grass that stretched around us for miles. His mirth was infectious and I felt something uncoil in my stomach. In that moment I knew that the memory of my serenader coaxing me into an awkward dance from another time had been safely tucked away, and in its place was blooming another more promising.

This was the bower in which your dreams found me, prone and outstretched for tenderness. They claimed descent from a gathering of dreams recounted by an ancient Sumerian myth, itself gathered over the course of a passage from dream to dream, civilization to civilization. The intertidal space where your dreams communed with those of your ancestor swelled with conserved anxiety. You regarded the reverb with forbidding and gloom like one would a shedding rose. For they seemed to augur to you the demise of your relationship with P. I gathered these petals and pressed them under my pillow. Like Ninsun’s blessings to Gilgamesh and Enkidu for their journey to the Cedar Forest. As Enkidu did with Gilgamesh’s dreams, I dove into your sea of misgivings and returned with good omens. With naive determination, I went about cultivating my bower. But the sea was already inside me.

The term ‘asaratos oikos’, literally meaning unswept room, denotes the quaint Graeco-Roman patrician practice of ornamenting the triclinia or dining room floor with trompe l’oeil mosaics ostending littered remains from a feast. Over the course of a banquet, inedible bits like bones, rinds, seeds, and shells would be compounded to these mosaics by the feasters, bringing the illusion to life. What may at a casual glance appear to be kitchen trash tipped out on the floor, was a carefully coded composition. The mosaics subtly denoted the host’s status by showcasing her access to exotic food items, often subjected to sumptuary laws. Asaratos oikos were oddly anachronistic in that they greeted their audience with the aftermath of the feast—an advance reminder to enjoy it while it lasts. Promising and sobering by turns, they functioned as memento mori, betokening an end to the feast as well as the flesh sustained by it.

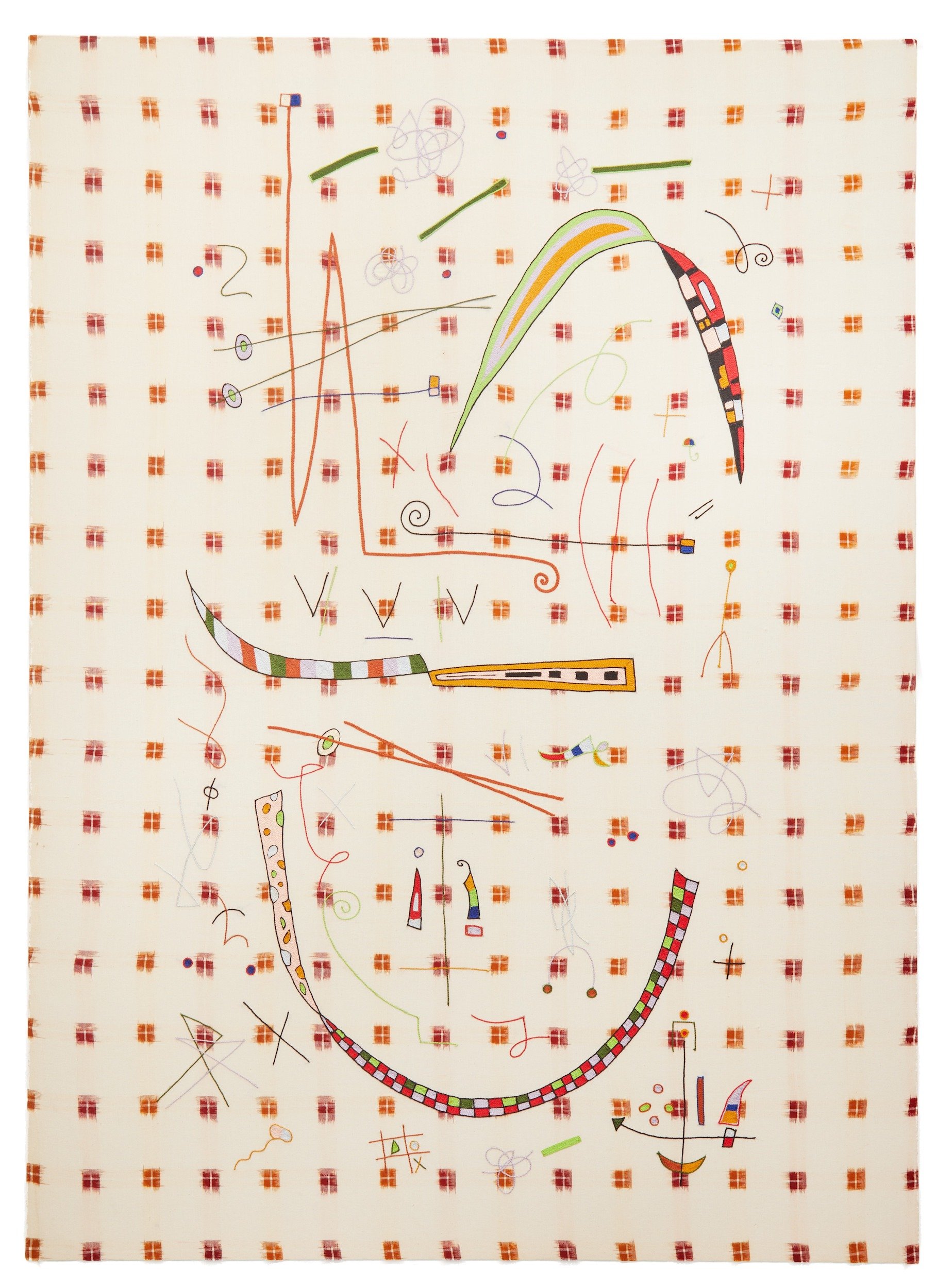

Heavy with prognostics, the unswept room motif appears on the first of five embroidered khadi towels comprising Oneiria. The series alongside the set of corresponding handkerchiefs, ‘Fragments’ were originally commissioned for the 15th edition of the Queer Arts Festival in Vancouver (2022). Katki’s take on the exhibition theme of apocalypse, Oneiria took as its point of departure an exchange recounted by Tablet IV of the Sumerian epic of Gilgamesh where the eponymous hero relays a quintet of dismal dreams to his friend Enkidu as they journey to the Cedar Forest to kill Humbaba. The artist marinated these mythical dreams with anxieties of his own by letting the fretful contents of Tablet IV seep through his subconscious. The resulting phantasms were systematically documented in a dream diary. It is this angsty compost cluttering the mind that is picked out in thread across the five panels of Oneiria.

Areez Katki, Oneiria: Night 5, 2022, cotton embroidery on khadi towel, 136 x 71.6 cm

In its original iteration at the Queer Arts Festival, the panels were suspended from the ceiling in loose imitation of the transient camp built by Enkidu for Gilgamesh night after night in the wilderness surrounding Mount Lebanon. The artist had reimagined this encampment as a dream house for sharing apprehensions, care, and intimacy. The dream house was a place for Gilgamesh to rest his chin on Enkidu’s knee and drift into sleep; a place to startle awake in the middle of the night and have his fears soothed by his companion. In Katki’s vision the dream house figures as a makeshift refuge not just from a hostile environment but also from worldly quests, complete with domestic furnishings like blankets, tinctures, amulets, flasks, boxes, and even weapons of survival. It is lodged in a time fracture where the heroic sequence is temporarily suspended to make room for domesticity and vulnerability that are distinctly unheroic.

On his first night of induced dreaming, Katki, like Gilgamesh, found himself in a dream house tucked away in the lap of the Zagros mountains (the three triangles joined at the hip being the symbol for mountains in Sumerian cuneiform). The floor of this shelter bore an asaratos oikos recalled from the Vatican Profane Museum. As he studied the patterned tesserae the earth started rumbling and the mosaic quivered into life. Its sight made the artist fretful both on account of the animated offal and the fate it augured for his relationship. What if the unconsumed food that the Romans discarded to the floor were offerings to the dead all along, not unlike the libations of flour made by Gilgamesh every evening in expectation of omens from Shamash, the sun god? Would this make Oneiria an attempt on the artist’s part to seek guidance from his mythic forebear in the face of imminent doom? The loose teeth, pottery shards, dead fish, and exclamations of horror sprinkled across the panels would then appear to be subconscious regurgitations mingled with remains of a crumbling world.

Katki’s rendition of asaraton oikos reads like the cataclysmic aftermath that finds the dream house in disarray. The household effects that once connoted comfort, care, and convalescence lie across the floor forgotten. The soft enclosure for nurturing vulnerability has proven itself vulnerable to the forces outside. A dream ended can be an apocalypse begun. In the bottom left corner of Oneiria: Night 5 a self-referential figure can be seen eschewing the double encirclement of the lover’s arms and the dream house. In its single-minded determination to get away it has failed to account for an approaching vehicle and is subsequently sent flying by the impact. The collision has transformed the figure into a bird that soars away to freedom. In its wake, the entwined hands symbolically captured by the cuneiform in Fragment 2 have been left grasping at a familiar form (Oneiria: Night 5); the tongue that out of habit starts forming the lover’s name finds itself unable to go beyond the first letter (Onieria: Night 5); the chin that used to melt on the lover’s knee has been recalled into a protective hunch (Lot. 4: As this chin melts on your knee).

In its re-interpretation of asaraton oikos, Oneiria cast the chin, the tongue, and the hands as pieces of a puzzle that evoke scenes of queer intimacy rehearsed within dream houses across time. Here, these disembodied parts signify both the material traces of a past relationship, as well as the ghost memory of shared choreographies, dispositions, and rituals that linger in these parts. Katki’s dream house opens a space beyond history, progress, and nations where queer temporalities of love, myths, dreams, and loss can congress. Given its compatibility with these alternative temporalities, the dream house can also serve as a probe for investigating the affects that abide within the shadowy recesses of history. In Katki’s hands, these biographical fragments become unassuming pegs whose durational insistence can cause cracks to appear within the monolith of history. Over time, these anachronous fissures may well create possibilities for righting historical wrongs.

Areez Katki, Three Clever Boys, 2023, watercolour on Arches cotton paper, diptych: top 29.5 x 21 cm; bottom 15 x 30 cm

The impulse to wander the bylanes of history, linger in painful reveries, and recycle trauma from the past is quintessentially queer. By dwelling on his experience of exile and the loss of connection to one’s ancestral land, Katki seeks to expand the archive of anxieties inherited from his migrant parents. As a queer Parsi who migrated from Mumbai to Aotearoa at an early age, Katki is deeply aware of the labour of integration that a migrant is expected to perform to fit in better. Echoing Sarah Ahmed’s notion of privilege as an energy-saving device, Katki’s oeuvre instantiates the constant friction that one has to overcome as well as the myriad ‘straightenings’ imposed on those who fall outside the pale of privilege.[1] The exacting demands made by the dominant culture on a body that is deemed foreign to it often fold in the body a sense of inferiority, fear, and self-doubt even when one has acquired a certain mastery over that culture. Recent attempts by the artist to reclaim his left-handedness—a queer tendency that was culled during childhood—in some of the preparatory drawings for the large textile panels from 2023 evidence the innovative and impressive repertoire of rebellion summoned by migrant bodies against dominant cultural fit.

Throughout the current body of work, we notice a use of history that can be termed queer. Katki deliberately hones these unexpected and at times irreverent modes of accessing and mobilising the past (which Ahmed might approvingly describe as queer vandalism) perhaps as a corrective to the differential resistance that the discipline has developed over the course of its established use.[2] This resistance can prove particularly prohibitive to those in the margins who aspire to get their stories admitted into the high annals of history. Faced with systematic exclusions produced by inherent resistances that are as unforgiving as they are relentless, Katki seems to have come up with a reworked mandate: throw a wrench in history.

Abandoning the so-called scientific and objective disciplinary approaches in favour of an affective approach that openly traffics in emotions, dreams, myths and fiction, Katki attempts to veer history away from its violent tendencies. Undergirded by a reformative intent, the works stake a personal relationship to archives that opens their contents for more democratic interpretations and uses. In a context where there is little to no historical material that can reinstate the link to a distant past, owing to loss or loot, tropes of fiction—in particular myths, hyperstition, and dreams—can come in handy. Katki’s recourse to fiction then is not simply a matter of improvisation but an affirmative act of reclamation that upholds Indigenous modes of apprehending the past—practices that have been summarily disbanded, carelessly displaced, and deliberately downplayed by colonial epistemologies and their continuation in the present under various guises.

Pediment and Frieze is a series of nine watercolour diptychs that peruses the remains of the Achaemenid empire from a queer Zoroastrian vantage. For its subject matter the series primarily looks towards the ruins of Persepolis—the ceremonial capital of the said empire destroyed by Alexander of Macedonia in 330 BC—studied during a field trip in 2018, followed closely by various articles of Achaemenid heritage purloined under the aegis of colonial authorities during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, that have since wound up at institutions like the British Museum and the Musée du Louvre. Inspired by a reparative socio-historical exercise conducted by the National Museum of Iran (Tehran) whereby the museum asked children to submit drawings of artefacts epitomising Persian identity, the artist has combobulated an archive of his own that reimagines a rapidly fading past several times removed. Archival fabulations like these can be crucial from the standpoint of re-furnishing a link, however tenuous, to a fleeting source, thereby bolstering one’s sense of social belonging.

Areez Katki, As this chin melts on your knee. Installation view, TARQ Mumbai

Alluding to the architectural features often reserved for visual communication of ideologies, Pediment and Frieze derives a number of motifs from the allegorical reliefs ornamenting the Persepolitan ruins. The disjunct framing, watery facture, and saturated colour scheme are all devices meant to highlight the loss of lived meaning that results from the scrubbing and decontextualisation of artefacts. Thus, for example, the colours in Capital & Base reimagine the pigments that would have once adorned the monochromatic masonry that presently lies scattered across the citadel grounds; the background in Ascension toward the garden invokes the yellow uniforms mandated for Zoroastrians at the head of their persecution from 8th century onwards; the aqueous rendition of the gold and silver dish embossed with a twelve-pointed lotus—a Zoroastrian symbol for the Ashem Vohu prayer—in Two Lions Ten Prayers recollects the moisture that would have inhabited the bowl ritually. The loving diarising of these ancient colours, symbols, and residues does not simply bemoan the loss of heritage but also rejoices in their dogged persistence through the corporeal repositories and material practices of its dispersed descendants.

On the whole, the tremulous impressionism cultivated by Pediment and Frieze serves to animate the compositions into dreamlike tableaux, allowing the artist to mine alternate significations and affects from the objects chosen for representation. Like their promiscuous outlines bleeding into each other, Katki’s compositions appear to be caught in a moment of metamorphosis, quivering with queer possibilities. It is worth mentioning that there are multiple registers within which queering operates throughout the series, ranging freely between literal and metaphorical, momentous and banal, sexual and sensual. In Ascension toward the garden, we find two courtiers in a queer position—sitting astride a horse with their backs leaning against each other. Treasury offers vignettes into the absurd opulence of the Achaemenid court, highlighting its campness through the humorous juxtaposition of an attendant carrying an elaborate pitcher, a donkey’s derriere, and a pink parasol shading a ruler who has been cropped almost entirely from the scene. Wind from the northern front envisions a reversal of the aeolian and depredatory erosions implied by the Sistan Levar wind, through its rendering of the arid landscape of Fars—or Pars province of Iran, the point of origination of Parsis—into a verdant oasis, a fecund ground for nascent homosociality.

Areez Katki, Small Vessel/Big Container, 2023, cotton embroidery on found cloth, 153 x 108 cm

Throughout Katki’s oeuvre vegetal matter vibrates with desire, sexuality, and youth. Its deliberate exhuming in this series—in the form of palm fronds, evergreen cypress trees, and lotuses—is a calculated exaggeration of the sexual tension implied by queer arranging of soldiers that run aslant to the expected order. The conflation of vegetal and sexual efflorescence is nowhere as apparent as the series of embroidered panels inspired by the formalist tenets of Paul Klee—in particular his pedagogic didactic of taking a line for a walk. The self-evident titles of these works offer keys that can help unlock the conjugations codified by the visuals: Blossoms (after P. Klee), Fragmented Awakening (after P. Klee), Parcel of Stems (four soldiers at ease). The last is particularly noteworthy in that the medium switch to embroidery has enabled the artist to exchange the telltale rigidity of imperial soldiers with the fluidity of flowers. This stylised reinterpretation of a Persepolitan bas relief where the military stance and accoutrements have been cast aside for vernal languour, slices open the straight time of the empire, infiltrating it with queer moments. Instantiations such as these situate Katki’s historical project beyond straightforward attempts at recreation, tickling disciplinary lines with pleasure.

The centrality accorded to pleasure in queer accounts of history is elaborated at length in Elizabeth Freeman’s book Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories. Significantly, her notion of ‘erotohistoriography’ clings particularly well to Katki’s caressings of ancestral past:

Erotohistoriography admits that contact with historical materials can be precipitated by particular bodily dispositions, and that these connections may elicit bodily responses, even pleasurable ones, that are themselves a form of understanding. It sees the body as a method, and historical consciousness as something intimately involved with corporeal sensations.[3]

Areez Katki, As this chin melts on your knee. Installation view, TARQ Mumbai

The looped rhythms of bodily sensations and historical awareness are underscored by the current body of works which recounts pleasures occasioned in the present by an exhuming of past pleasures.

The self-referential ‘Anointed’ series ostensibly catalogues the inexplicable sensations and impertinent associations that play out across the body bent in a historiographical pursuit. The work chronicles memories of chance yet significant encounters with organic materials: green earth, lapis lazuli, saffron, and vetiver. Invoking the gesture of smearing the body with these historical materialities, Anointed literalises the notion of erotohistoriography. Anointed 4 uses a vetiver attar roll-on recovered from Katki’s grandfather’s drawer to trace the impression of his knees, folded underneath him in an attempt to pull out the fragrant roots of the said grass in a friend’s backyard in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland. Similarly, Anointed 3 uses saffron oil and watercolours to recreate the memory of an unseasonal gathering of saffron crocuses by women—a startling burst of purple across a ground composed of pale green, yellow and reddish soils—witnessed during a meandering northward journey from Greater Khorasan region towards the Caspian Sea. The body bears memory of these materials—historically used for consecration by dabbing—as these materials have been made to bear the memory of the artist’s body.

Areez katki, Anointed 3: Saffron, 2023, mixed media on Arches cotton paper, 31 x 31 cm

Echoing the schematic representation of the sights and motions familiar from the makeshift laundry room at his grandparents’ apartment in Tardeo (Mumbai) by the embroidery titled Sight of wet laundry, Anointed 1 touches off the memory of the sky reflected in the rainwater-filled impressions left by the artist’s knees in the soggy ground as he stooped to collect a sample of green clay from the banks of the Whanganui River. Anointed 3 uses the pigments processed from lapis lazuli procured from a small village situated along the Iranian border with Afghanistan to reimagine the Ishtar Gate currently housed at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin. The lapis lazuli glazed tiles from the gate that once stood along the lower Euphrates in present-day Iraq, were gradually pilfered by German archaeological teams over a period of 1904-1914. By fronting a corporeal and personal relationship to historical material, both these works qualify the acquisitive proclivities of archaeological missions that allow, to borrow Katki’s words, ‘only stains, traces and memories of Indigenous cultures to exist in the memory of those who have more direct connections with the land and culture from where those materials were sourced.’[4]

Addressing these concerns, Katki enlists the very matrix of archaeology—earth—for a cross-examination of its historical tendencies to appropriate, delegitimize, and dominate colonised cultures. Composed of kaolinite clay (harvested from his mother’s garden in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland) tempered with raku, grog, and sand from the Caspian Sea, these clusters of earth-based forms enact alternative modes of engaging with the past that do not entail stealing from it. Much as the other works in the exhibition, the earth-based works seek to reclaim a particular past—in this case, a neolithic Persian past—on their own terms. Feigning historical accuracy only to the extent that they mimic the low firing temperatures and rudimentary hand-building techniques such as pinching and coil prevalent during the third millennium BC, these works articulate a strong exception to the archaeological mandate that forcibly extracts antiquities from their semiotic economies, reducing them to post-colonial trophies offered for museological displays and ethnographic spectacle. This commodification and decontextualization of cultural heritage is what is parodied through the current presentation as auction ‘lots.’ The idea of organising the works as lots was previously tested by Katki in 2021 for Thieves’ Market to question the unfortunate typologies acquired by these relics of the past as they circulate within markets, estranged from their context.

Areez Katki, As this chin melts on your knee. Installation view, TARQ Mumbai

The Lots excavate the wounds inflicted by archeology while offering a salve for them. By prying out memories of loss, destruction, and exile from an ethnic past, the work simultaneously relates a counter-history of adaptation and survival, thus qualifying the popular notion of history as the victor’s account. Viewed in this light, works like Rhyton can be read equally as recalling the assimilative violence of cultural conquest—in this case the amalgamation of Elamite culture by the ascendant Achaemenid culture in the 6th century BC— and commemorating the inadvertent survival of Elamite motifs in the architectural idioms preserved at Persepolis, and now in Katki’s work, albeit in an abstracted form. Another story of counter-cultural resistance is hinted at by Lot 3: Poultice maker that fabulates the origins of the matriarchal cult of the goddess Ardevi Suri Anahita with its water rituals (a trope explored by works like Farvahar Redux that were part of his previous solo at Tarq in 2021) which formed a counter tow to the fire worship upheld by the dominant Zoroastrian strains centred on Ahura Mazda. Anachronistic in nature, the work invites speculation about the divinatory, healing, and architectural practices of this minor sect. Both Rhyton and Lot 3 situate the relatively recent plunderings of historical material by colonial archaeologists within deeper histories of patriarchal conquest, subsumption, and subordination.

Lot 1: The lover, the river and the cup brings the votive practices of neolithic matriarchal cults (encountered during a visit to Susa in 2018) in alliance with a fragment of mediaeval Persian queer history. The title is a shorthand for an inscription found next to a painting dated 1627 and attributed to Muhammad Qasim. It captures a romantic exchange between Shah Abbas I and his page, both reclining under a tree, surrounded by wine decanters, flasks and bowls. The inscription reads, ‘May life provide all that you desire from three cups: those of your lover, the river and the cup.’ Possibly an oblique reference to the aforementioned romantic paraphernalia, the pinch pots compositionally sit next to a female figurine reminiscent of the Venus of Tepe Sarab which has previously figured in Katki’s works. The votive significance of the original referents has been harnessed by the artist in this modern attempt at communing with his queer matriarchal forebears.

In a similar vein as Oneiria, Dream Valves revives archaic oneiromantic modalities that seek wisdom from dreams. The work invokes the first recorded instance of dreams attributed to the Summerian ruler Gudea. These cylindrical tablets dating back to 2120 BC convey the mythology of the construction of Ningirsu temple whose designs and building instructions were methodically revealed by the gods in Gudea’s dreams. Through its conscious cultivation of proto-writing and non-linguistic markings in the service of dream recording over a period of April-May 2023, the work repudiates the textual and other logocentric methodologies instituted by Western scientific paradigms that delimit Indigenous cultures’ access to their past.

The second in the ‘Disjecta Membra’ series claims a transtemporal genealogy. The series consists of nine tiles bearing the names of several exiled poets—Hafiz, Lorca, Agha Shahid Ali, Etel Adnan, Mahmoud Darwish, and C.P. Cavafy—separated by space and time alongside symbols of the old empire—the eagle seal of Achaemenid ruler commonly known as Cyrus the Great, and the Avestan cuneiform phrase ‘xsa’sa’ which means ‘old empire.’ Totemic by nature, the work initialises a trans-historical network of prominent queers and exiles whose poetic tools have been enlisted in the service of dismantling the master’s account of history.

The first ‘Disjecta Membra’ series (not included in the exhibition) remade the ritual of bird feeding practised by Katki’s late grandmother into a divinatory technique of communing with the ancestors and the land. There, instead of past poets, the artist invites birds with scatterings of bread and seeds to leave ciphers from realms beyond our consciousness on unbaked clay tablets. The gesture of feeding birds recollected by this work as well as the votive aspect of a number of Lots offer a corrective to the covetous leanings of archaeology by reframing it in terms of obligation and reciprocation. As imposters leading ostensibly different lives from their immured counterparts, the ‘Lots’ are anachronous sowings calculated to confound archaeological strata. Some day their remains will mingle freely with those of their antecedents, throwing a wrench in archaeology.

I remember being fascinated by a gold chariot, curiously yoked to four horses and driven by a cowled attendant. Beside him stood a monarch, his profile turned towards the viewer in a glower. Directly above the chariot hung two griffin-headed armlets, delicately wrought. Underneath the chariot was displayed an assortment of gold vessels. They formed part of the Oxus treasure excavated near the eponymous river in Tajikistan around the late 19th century. I had ample time to commit that glower to memory over the course of a part-time job at the British Museum while I was studying in London. Having registered its coldly censorious touch down my spine multiple times as I crossed gallery 52 or was posted there, I remember wondering about the transparency of my queer fancy for the armlets.

I can almost imagine the monarch smiling sagaciously now to see these words pour out of me like a libation to an ancient past I seemed to have accidentally touched. Or was I the one who was carefully selected and secretly honed as a vessel for over seven years? The past always finds its agents, bodies that it (im)presses upon to fount itself forth. What if time was an armlet bent over itself and the past—like conjoined griffins—was crooning to us from the future? In hindsight, I can see myself clearly being led by the reins to this juncture where I would greet my former self in the present portrait of the enigmatic eight-legged horse suspended mid-gallop. The past not only burdens and drags. It can also suspend and uplift. Can you hear its buoyant croon?

[1] Ahmed, Sara. Kessler Lecture: ‘Queer Use’ presented at CLAGS: The Center for LGBTQ Studies, New York, 2017. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O8Y_P27vVAQ&t=4200s

[2] Ibid.

[3] Freeman Elizabeth. Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories. Durham [N.C.]: Duke University Press, 2010, pp. 95-6.

[4] From the notes shared by the artist dated 18 December 2023.

Adwait Singh on Areez Katki’s exhibition As this chin melts on your knee, on view at TARQ Mumbai through 24 February 2024.