“Māori control over Māori things”: Elisapeta Hinemoa Heta on Te Ao Māori Exhibition Making

Alanna O’Riley interviews kaihoahoa whare (architectural designer) Elisapeta Hinemoa Heta (Ngātiwai, Waikato Tainui) on the importance of place, community, and agency, on the occasion of her recent exhibition Pouwātū: Active Presence with John Miller (Ngāpuhi) at Objectspace.

John Miller and Elisapeta Hinemoa Heta, Pouwātū: Active Presence. Installation view, Objectspace, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, March 2021. Courtesy of Objectspace. Photo: Samuel Hartnett

Alanna O'Riley: Let’s begin with a question that I hope can act as a backdrop for this discussion. How do you define ‘community,’ and what influence does this have on your creative process?

Elisapeta Hinemoa Heta: It’s quite a beautiful question actually. I think it fundamentally relates to the way people identify as individuals and relationally to others. To me it's your sense of kinship or whanaungatanga and it's got a lot, in my mind, to do with support and aroha. All that stuff where you’re able to draw from a collective sense of self. It’s a very Māori way of thinking about things.

From my perspective, identity in te ao Māori is very pluralistic anyway so you're often thinking about yourself always in relation to the whole, whatever that looks like—whether that’s your whole iwi or your whole hapū, or your whānau, or your maunga or your whole moana. You’re always in relationship to those things.

Community to me is quite an amazing thing as it's where I would say I draw strength from. I think if you don’t draw strength from your community there’s probably an issue or you need to get help [laughs]. It’s an easy connection from there to my practice. Funnily enough I see that as one of the fundamental differences between contemporary art and contemporary Māori art in that our work is never necessarily about an individual pursuit. For me it's always about the pursuit of education or unearthing or expanding on our mātauranga (knowledge), our wairuatanga (spirituality), all of the tangas that effectively connect us to one another.

I joke about the fact that when people ask what kind of art I make, I never know how to answer. It's always about the kaupapa, and in architecture the thing I’m most fascinated by is people. The built environment outcomes are a really wonderful consequence, or they can be a really terrible symptom of the community. So, for me my practice regardless of what it is, whether it's writing or designing or singing waiata, is all about this connective whanaungatanga that all goes back to that idea of being part of a bigger picture. So not an easy question, but it's interesting because it's fundamental for me. I would definitely characterise community to be more whanaungatanga because community as a term has so many hang-ups and assumptions of meaning.

John Miller standing within Pouwātū: Active Presence at Objectspace, March 2021. Courtesy of Objectspace. Photo: Samuel Hartnett

John Miller and Elisapeta Hinemoa Heta, Pouwātū: Active Presence. Installation view, Objectspace, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, March 2021. Courtesy of Objectspace. Photo: Samuel Hartnett

I had the pleasure of seeing the exhibition and was struck by John Miller’s incredible photographs, but more so I was in awe of the wharenui you constructed within Objectspace and all the tikanga around it like the taking off of the shoes, the waiata you sang. I described it to you as being a living and breathing space. Galleries can often feel quite cold and dark, and I’ve never seen an exhibition quite like it. How did you get involved in Pouwātū and what was your approach to designing the exhibition?

Megan Tamati-Quennell approached me after speaking to Brook Andrew, the artistic director of NIRIN [22nd Biennale of Sydney], about the Ghanan Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale in 2019. Instead of just putting their art up in a gallery, the artists of the Ghanaian Pavilion worked with David Adjaye to rearticulate the spatial experience of the gallery and the artwork together. Brook was really curious about how we could exhibit John’s work at NIRIN, but not just hang photos on a wall and call it a day. His provocation to Megan was, ‘how do you do a Māori photography exhibition, what does it look like to present photographs in a Māori way?’ So, Megan said she knew a young Māori architect who would be the best person to work with John. And that was a really lovely introduction.

I really liked that provocation that Brook had started with, the whole idea of how you might approach the presentation of photography in a Māori way even though it's a Western technology that’s been brought to Aotearoa and very much adopted into our lives. That was my challenge.

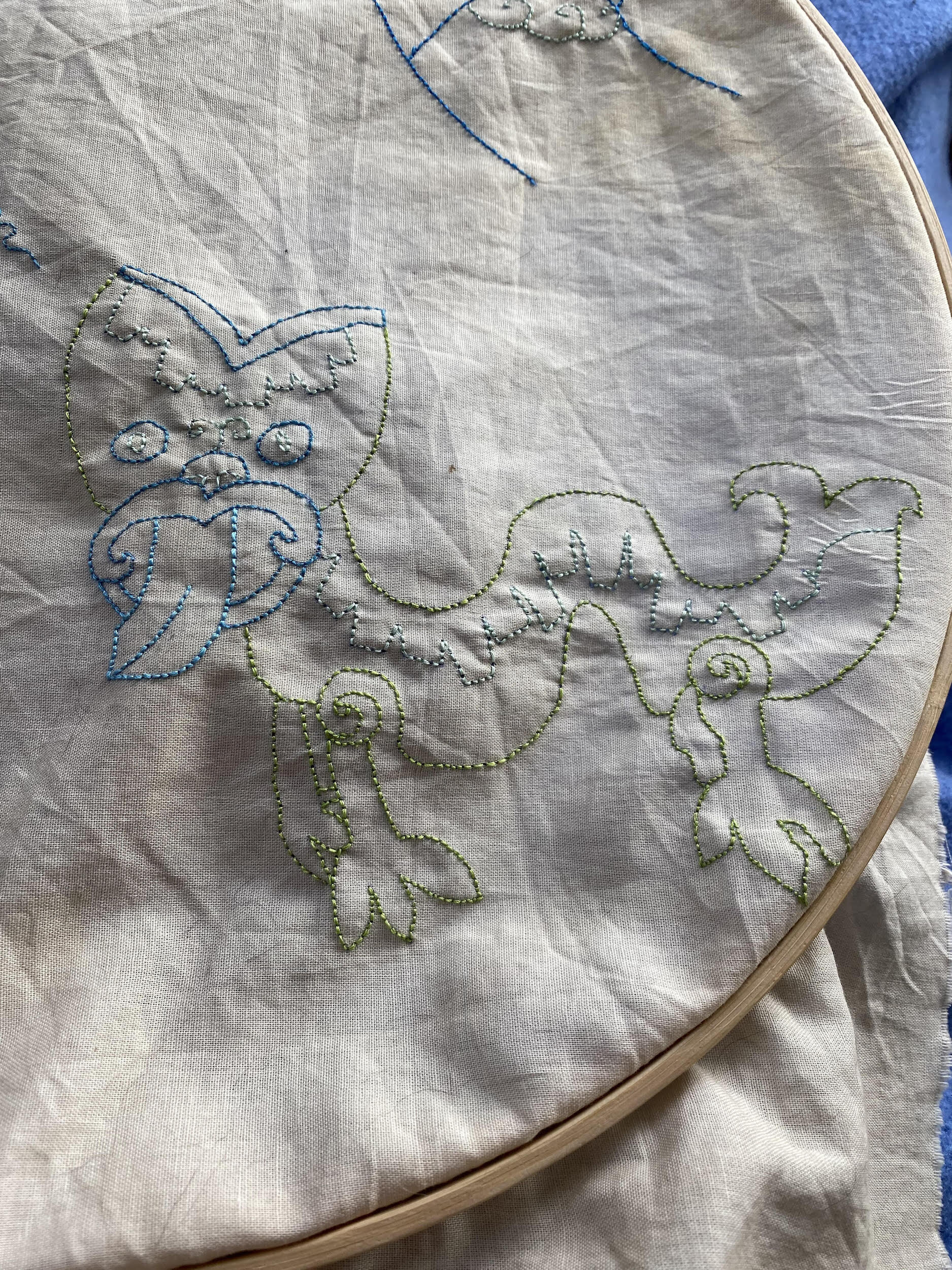

The long and short of it was that I went to John’s studio, sat with him for several hours, just kind of masticating over his work as he showed me photographs from far and wide. And it was at this meeting that I told him about one image that had stuck with me for a really long time (and I didn’t even know it was his until that day) of the first meeting at Te Kaha Marae of Ngā Puna Waihanga, the artists and writers’ group that became Ngā Puna Waihanga later on. The image is of a Sunday morning service in front of the whare at Te Kaha, with the pews facing the whare. You’re used to seeing the pōwhiri occur on the ātea (courtyard) [with people facing outward] but in this case, because the pews are facing the whare, everyone’s backs are to the image. I really loved that visual. It’s very simple and very beautifully set up. For me it was this pivotal moment in time of the meeting of a community, the wharenui, and then the hybridisation of the church service in the space. I discussed the image with John and we spoke about that day. I started there because, and I think about this in architecture a lot, those thresholds into space are really important. And basically, I wanted to design a space that was a vessel for his work.

The other concurrent thought for me was something Bruce Stewart said to me. Bruce passed away a few years back but was the kaitiaki (custodian) of Tapu Te Ranga Marae which burnt down last year. Bruce used to talk about how when he was in jail he read this book that said our wharenui are the place we’re born, the place we die, they’re our libraries, they’re our schools, they hold our stories, they hold our tears, they hold our happiness, they’re this repository for things. And to me this is very obviously what John’s photographs are doing so I wanted to use the framework of a wharenui to effectively curate and conceptualise the way his photographs would work within the space. Our wharenui are tipuna (ancestors) or sometimes they’re atua (god). But in this case, it’s about a concept or a whakataukī (proverb).

I wouldn’t describe myself as a curator because that seems very bold but I was really conscious that I was making this space and I had to be quite mindful about where John’s photographs would go and how they would be displayed. What stuck with me after our first meeting was John’s casualness with his photographs. It was like sitting in someone’s house and them getting the photo albums out and you’re just flicking through. You touch them and you hold them and you move them and he’s laminated them which just blows my mind, he chucks word art on them and gives them to people. He’s just so casual with the use of them, but it’s deliberate because for him he’s not taking photos to be sold in dealer galleries, he’s taking photos to capture moments in time. They’re an extension of his experience. And so, I wanted the photos to feel like you could touch them, like you could handle them in some way, which is partly why the photographs are not framed.

John Miller, Whetu Tirikatene-Sullivan, Dining Hall opening hui, Te Hauke Marae, 1975. Courtesy of the artist

John Miller, US Black Panther Support Rally, American Consulate, 1972. Courtesy of the artist

John Miller, Māori Land March, Wellington Motorway, 1975. Courtesy of the artist

John Miller, Evening Supper, Dining Hall, Te Kaha Marae, 1993. Courtesy of the artist

It sounds like it really relates to the doubled name of Pouwātū and the idea of ‘active presence’?

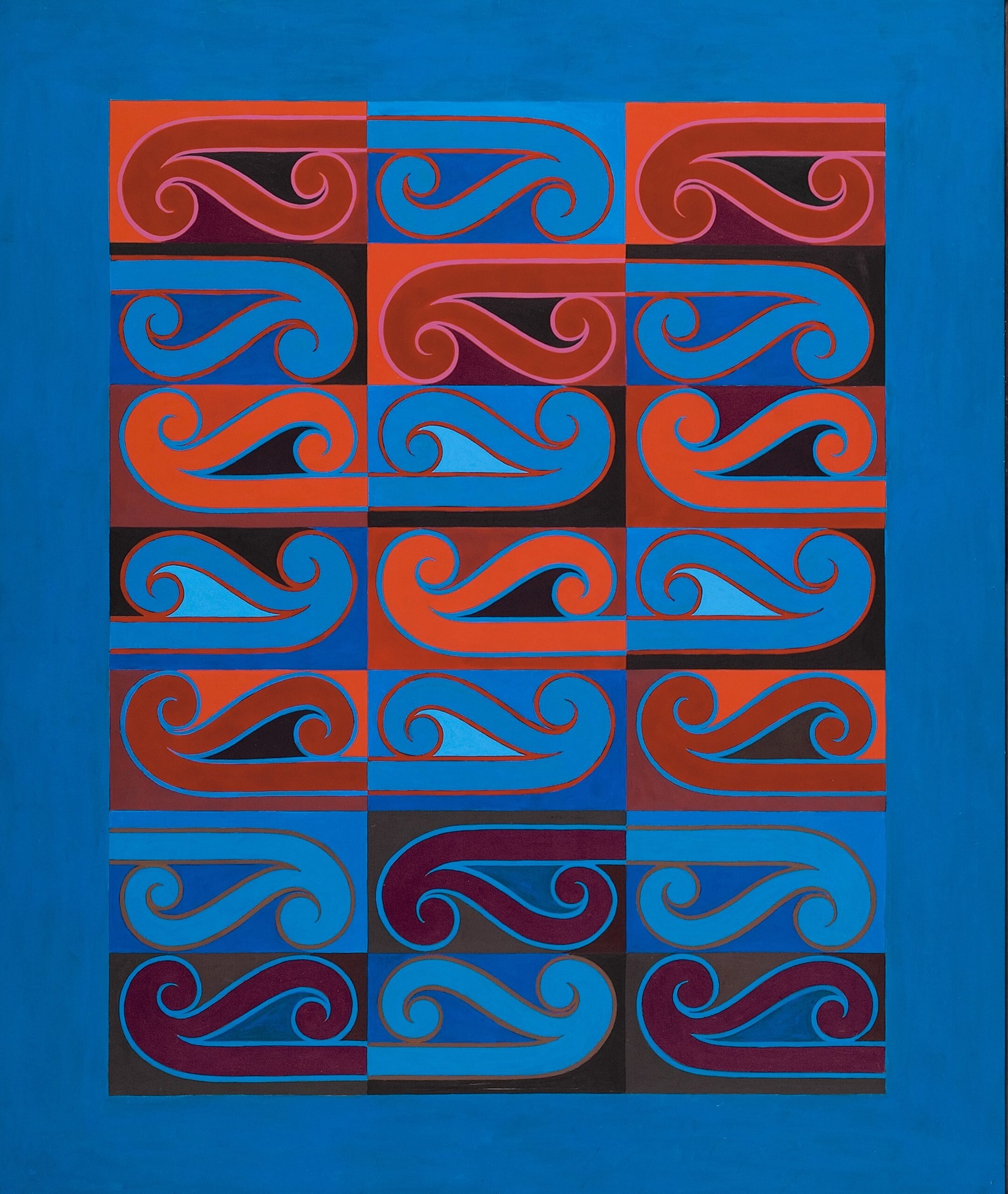

Yes, and that’s where it came in. A lot of people talk about John as a protest photographer. And in a lot of ways, he is, because he was and is in every damn protest. But I don’t know that he would be a protest photographer if Māori didn’t have so much to protest about. To me, he’s documenting Māori life; he’s documenting significance and the ordinariness, everything that Māori do. The joy and the beauty, the sadness and the seriousness, the ferocity; it's all in there. He’s just constantly there, he’s an active presence. And so, I tried to think of the Māori equivalent to that.

Pouwātū isn’t a word, I made it up. Pou are inside a whare, they represent something significant, a moment in time. You have poupouwhenua which are out in the land, but pou can also mean something that stands tall and strong, that is not static but present. And then wā relates to time and longevity, a sense of time and space. And tū is to stand upright. So Pouwātū was the closest approximation I could make to the idea of active presence and it’s how I would describe John: strong and present and resilient for Māori. So that’s where that name came in.

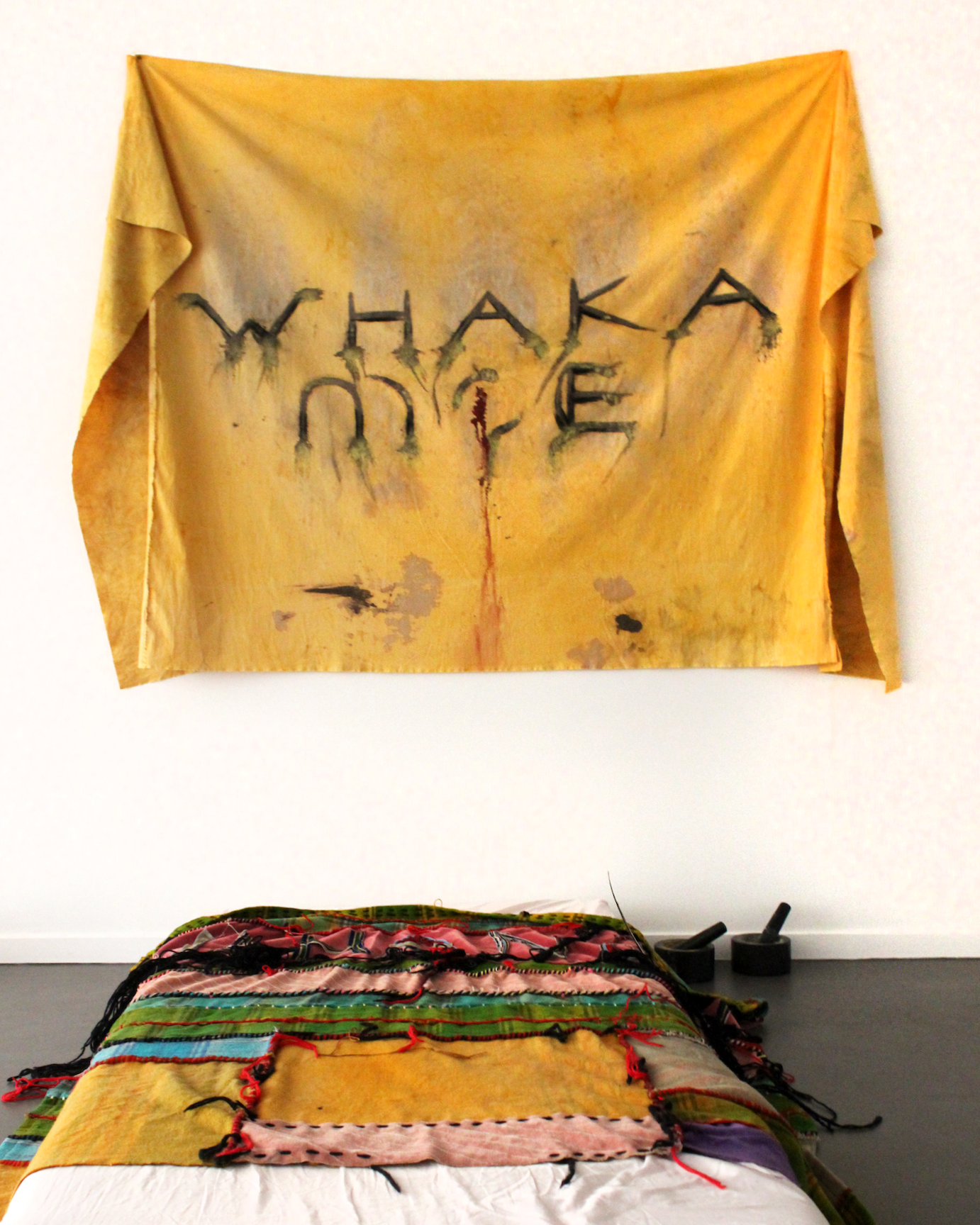

I wanted the whare to be warm and I wanted it to be tactile. I wanted those walls to come out so people could sit in them, like you do in a whare; you stroke the walls, you feel enveloped. I still wanted that sense of movement although there were no carvings. John and I both come from the North and because colonisation and missionary relationships with Māori up North happened so quickly, a lot of our carvings were lost, taken down, thrown in the swamps, and so the enduring relationship there is that a lot of our whare don’t have carvings at all, all they have is photographs. So, it was really apt for John and I to both be from up North and for that to be a representation of how our pou are adorned. And then there’s things like the colour, [when we first showed the exhibition] in Australia the colour was slightly different to Aotearoa.

If I’m not mistaken it was a kind of orange colour?

Exactly. That was inspired by my friend Sarah Hudson who is a part of the Mata Aho Collective and is one of the wahine behind the Instagram account @kauae_raro who are doing all this research into traditional Māori pigments. I used one of their images and pigments as a reference. I chose that colour in particular because it felt fitting for the clay red earth colour Australia is associated with. It wasn’t to be cliché but it was more to be contextually correct. When coming back home, I wanted the colour to change because we’re in a different context. I wanted to soften it a little bit. Plus, I have this low-key desire to paint a wharenui pink someday because I just think that’s kind of amazing. We use colour to denote place—it's not corny, it's not trendy, it's not any of that—it's an expression of the whenua. The tone we’ve used in the gallery is intended to reflect this shift from Australia to Aotearoa New Zealand. And I never wanted the spaces to be white. Because a lot of John’s photographs are black and white, I wanted them to have a bit of contrast and texture again. It keeps coming back to texture for me.

In line with that, I wanted to ask how your approach shifted from Sydney to Auckland, the relationship between community and locale and how that plays into the exhibition?

In Sydney we were sitting amongst lots of other artists and there were lots of things going on. The element that has stayed exactly the same—just slightly different timber—is the table and the bench seats. Most people think that we’ve just bought these in from somewhere but I designed that table and chairs.

The table comes back to that first meeting with John, sitting around his lightbox and looking at images. It was an act of sharing, and I wanted to bring this association into a whare. I designed this oversized table to feel like lots and lots of people could sit and gather and spend time. And it's actually done its job. People normally do the loop and they leave, they don’t ever just sit; but every time I talk to the Objectspace team they say they’ve never had people stay in the gallery so long. And I think that is because the room has so many opportunities to sit and dwell.

Even the carpet, the amount of people who messaged me and said, ‘I’m lying down in your exhibition.’ And I’m like, ‘good, that’s the point!’ But you never get people going to a gallery and lying down, it’s just not a thing. Even if you have to lie down to view something, you do it and then you get back up. I really wanted it to feel homely. Which is why there is carpet. It gives that added softness and balances out the sound in the room which can be really bouncy and quite tinny sounding. I wanted the space to feel like you could have long conversations or even sleep in there.

John Miller and Elisapeta Hinemoa Heta, Pouwātū: Active Presence. Installation view, Objectspace, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, March 2021. Courtesy of Objectspace. Photo: Samuel Hartnett

It’s so beautiful to hear you speak about your curation of the space because every aspect is considered. It's not haphazard, it's intentional—constantly harking back to place and space and the people entering the exhibition.

So even, for example, the main threshold in the big opening wall, above that is two photographs of fresh water springs that John took about 35 odd years ago. When you walk into a wharenui, you always walk under the lintel and under the figure of a woman. That is deliberately to whakanoa, to cleanse, to denote the shift from outside to inside. Therefore, those two images of water are there to cleanse, to change your mindset. The taking off of the shoes is more about those images than it is about the carpet.

The images on the back wall represent this really beautiful balance between the old forest and really powerful moments. You’ve got this big forceful energy and big quiet energy. The whole room is meant to constantly balance itself. Everything is a negotiation of the spiritual and physical connection. I’m a nerd for all of that [laughs]. But I think that’s why the show feels very Māori because every tiny detail has been approached through that lens: how might you balance the space, how might you think of tapu, how might you consider how people are going to feel in this room, or how you want their mentality to change when they come in. I’ve only been in a few gallery spaces that are asking you to think in that way.

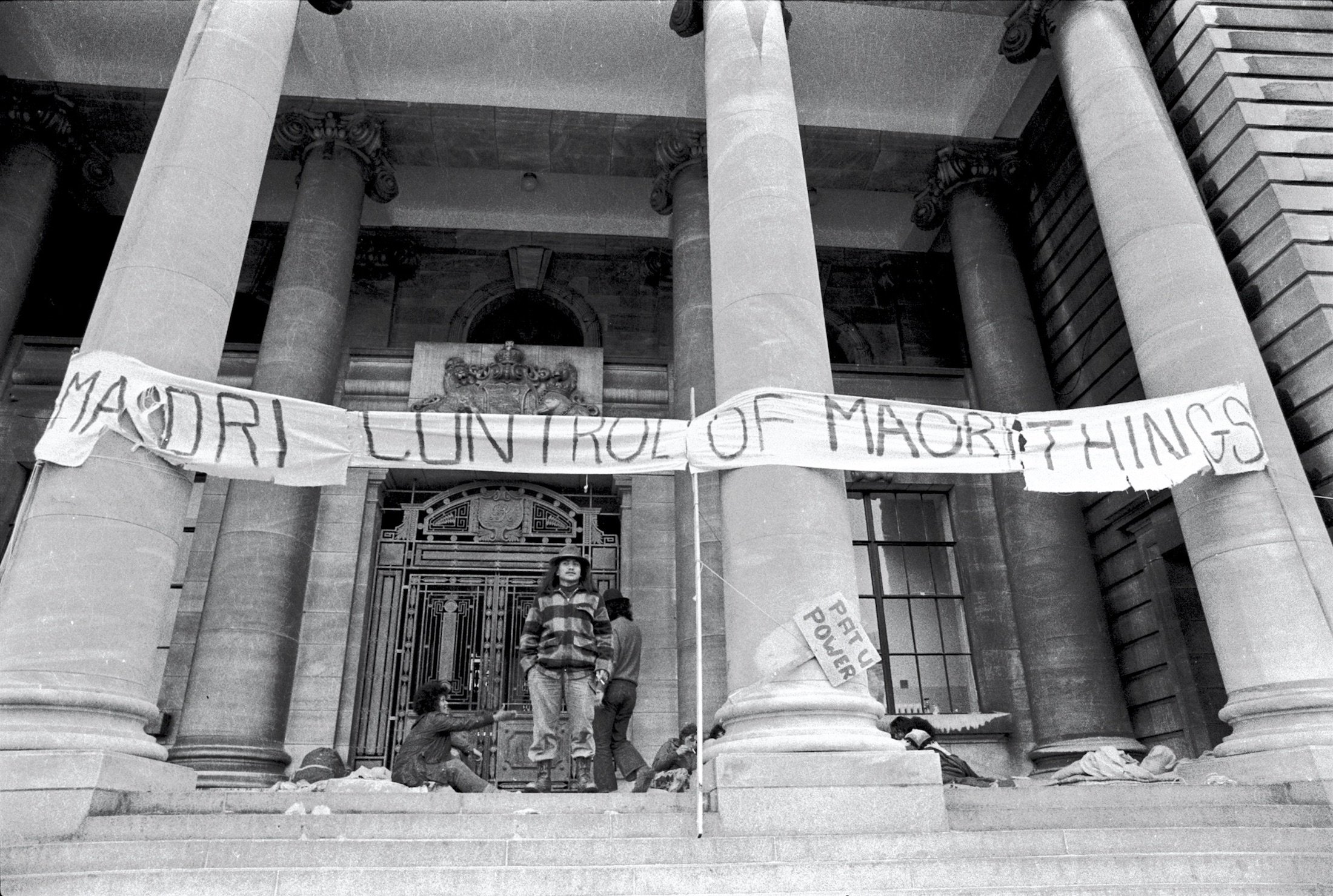

In relation to that I wanted to touch on your speech at the exhibition opening where you spoke about the notion of ‘Māori control over Māori things’ which I know is a statement in one of the photographs. How important do you think it is that Māori have sovereignty within creative spaces, that Māori have control?

Massively. Control is a tough word as people might think of dictatorship or authoritarianism, but I’m thinking of it from the perspective of mana and sovereignty. Really, it’s about agency, the total stripping of agency from Māori, and rebuilding that agency. I can’t underscore it enough. It’s majorly important. And even in the way that Objectspace were able to facilitate mine and John’s ability to do what we needed to do inside that space was the most perfect example of how you can give Māori agency without it being a song and dance. It’s implicitly a part of what the gallery is trying to do every single day and they are not trying to seek kudos for it. That’s why John and I feel so comfortable there. And it's not just about the space physically but it's also about the fact that they, as hosts, as kaitiaki of that space, gave so much support and comfort and aroha that it’s an easy task, it’s easy to work with them.

John Miller, Tame Iti (Tūhoe) at Ngā Tamatoa ‘Tent Embassy’ occupation. Parliament’s grounds, Wellington, 1972. Courtesy of the artist

And do you think that comes a lot down to Objectspace’s approach as well as yours and Johns coming into it—it’s as much a responsibility of the institution as it is the artists or curator?

Absolutely. It's the product of every single staff member. Everyone is very generous and approachable and affable and there’s always a sense of accessibility in that space. Institutions or organisations talk about manaakitanga (hospitality) or kaitiakitanga (guardianship) but Objectspace don’t need to, they do it. It sounds a bit corny to say that but it’s very true. There’s a very humble nature about that place. They are genuinely using their platform for the artist, not for themselves as a place that houses artists. I think there are other galleries that do that in various ways, each grappling with their own cultural and political landscape. So, you're right, it is the confluence and coming together of me and John and the Objectspace team. It was also apparent in the curation of all the other artists in the space. To have that many Māori artists in the space, they’ve never had that before. And it wasn’t like, ‘oh we’re going to plug Māori artists,’ it just kind of happened. And this again was a great example of the implicit nature of doing things rather than forcing them to happen.

John Miller and Elisapeta Hinemoa Heta, Pouwātū: Active Presence. Installation view, Objectspace, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, March 2021. Courtesy of Objectspace. Photo: Samuel Hartnett

You are also an artist yourself, does that have an influence on your creative process? As you say, you don’t want to say you're a curator, but does your artistic side, or perhaps your architectural background, inspire your approach to curation?

It’s funny, you know. I think I’m an artist when I’m inside a gallery and then I’m an architect when I’m outside of it. For whatever reason this has been the only time I’ve been referred to as an architect inside a gallery. I don’t personally have a different approach to art or architecture, it’s just that the medium and the budget changes significantly between art forms [laughs].

I was really nervous the whole time, if I’m honest, that my desire to look and function in a particular way was not going to balance with John’s work. I kept saying ‘oh it’s not about me, I’m just trying to house John’s work appropriately.’ And that was definitely the case in Sydney but when we came home that shifted, I felt more like I was John’s equal. In Sydney I was focused on being subservient to John’s mahi but I realised that when you’re thinking about minimising yourself like that you’re not thinking about the mana of your work and its contribution to the whole picture. So, to answer, ‘are you an artist in the space?’, I was almost trying to be invisible in Sydney. But coming home, I think I got to be a bit more true to my sensibilities whether that be in art or architecture. I think they both sort of folded in.

I get a bit frustrated with the distinction between art and architecture. If you think of a wharenui in a traditional artistic sense, our tohunga whakairo were artists. So, I’m getting closer and closer to this idea that art and architecture are the same thing. The thread I draw is that architecture is about storytelling through form and the physicalisation of people and place. It’s a confluence of past and future, just like art. That’s the curvy line I draw between my art and architectural practice.

My last question for you is: what’s next?

I constantly have a million ideas, which is a bit of a problem for me [laughs]. I’m being a bit mindful of my time this year. I’m trying to make it so that I could actually call myself an architect, which is basically like doing another master’s. I’m also receiving my moko kauae in a few weeks. I’ve got a lot of big life things, big milestones happening this year. I am the kind of person that tends to overwork so this year is about those things.

At Jasmax we’re doing some really big projects, including projects with Parihaka, projects with the Ministry of Justice; really hard-hitting stuff that’s quite intense. What is important for me about those projects is creating better outcomes for Māori. And that’s the thing that is really profound about my work in architecture, I get to have an influence in a way that is really, hopefully, impactful. Art is really beautiful because it has an immediate impact and you get to do it in a much shorter time frame but it doesn’t always necessarily have that same static-ness, it can come and go, particularly with what I do.

But that is the most significant part of Pouwātū. Because of the sheer gravity of John’s photographs, it's probably been my first time doing something that’s genuinely having an impact on the Māori community. The exhibition has brought more Māori into a space they wouldn’t usually come into, to experience photographs that they usually would not have otherwise seen. The amount of people that have come in that have said ‘I was there that day’ or ‘my mum is in that photo’ or ‘I never knew about this.’ It has been just such a privilege to be able to house that sort of thing. That’s the goal if ever there was one.

The above interview is based on a conversation that took place between Heta and O'Riley on 24 April 2021.

Robbie Handcock speaks to Wai Ching Chan and Tessa Ma’auga about their current collaborative exhibition Kāpuia ngā aho 單絲不綫 at The Physics Room, Christchurch.