In Conversation with Wong Ping

Sam Gaskin spoke to animation artist Wong Ping over Zoom about Fables 1 and Fables 2—on show through 29 May at Gus Fisher Gallery, Tāmaki Makaurau (Auckland)—and making art in Hong Kong under increasing political pressure from Beijing.

Wong Ping, Wong Ping's Fables 2, 2019. Installation view, happiness is only real when shared, Gus Fisher Gallery, March 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong/Shanghai; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York/Los Angeles. Photo: Sam Hartnett

Sam Gaskin: You have some intriguing bios posted around the internet. On Vimeo you’re “a comedian based in Hong Kong.” On Instagram you’re a “devout atheist,” “optimistic pessimist,” “weekend vegetarian,” and “silent neighbour.” And in an introduction to Fables on IMDB, it says, “Wong Ping urinates twice before gently pressing your head down with his right foot, giving you a closer look at your own reflection in his urine.” Which is the real Wong Ping?

Wong Ping: My style of writing is to reflect something, like a mirror. I’m not going to tell anyone anything, but reflect norms through my observations. And for the one on Vimeo, I feel more and more my writing process is like a comedian’s set. On stage they make hundreds of jokes that are maybe unrelated, but they have a line to wrap it up. I feel like my videos are the same — they’re a combination of everything I’ve been through over months, like a diary. The Instagram one is just a laugh. A weekend vegetarian sounds ridiculous but it’s not a harsh judgment, I’m just laughing at these things — I have friends who are only vegetarians on a Tuesday or a Wednesday.

You’ve said, “I hope Wong Ping's Fables can one day replace Aesop's Fables in the library.” What’s wrong with Aesop’s Fables?

They’re not practical now, for the contemporary time. I’m not sure they’re dishonest, but they’re too pure. It’s in an ideal world, a utopia. Let’s say a story tells you to treat your parents well, you should see them every day, spend more time. Of course that’s nice, but in the world it’s not practical. We have limited time, we live separately, we have friends and partners so we have to sacrifice or divide our time.

“When we talk about freedom, the artist should have the choice to say, ‘oh I want to openly discuss this’, or, ‘I want to make an abstract work.’ When people talk about making work in mainland China, I feel their frustration.”

Fables often appear light-hearted, but they often use animals as stand-ins for humans, as a tool to teach us the 'right' way to behave. But in your stories, the animals are already doing very human things, they start businesses, they go to jail, and so on.

A huge number of fables use animals as a metaphor, and I just copied the same formula. It gives me more freedom to do things that are terribly wrong, where people would normally have more empathy. It’s a way to cheat. These days people can be so sensitive, and a creator can self-censor. I’m thinking how far can I take this? If I can say really mean things, really terrible things using animals, and people still feel nothing, I would feel weird. The concept is wrong because I’m still a human writing it. Sometimes I try to test that line.

Before using animals, I already took advantage of animation. When I explain my own deep secrets or desires or fetishes in an animation, people don’t take it seriously. They don’t trust that it’s about me, they don’t believe it. I enjoy that ambiguity. It gives me space to push the script.

Wong Ping, Wong Ping's Fables 2, 2019. Installation view, Gus Fisher Gallery, happiness is only real when shared, March 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong/Shanghai; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York/Los Angeles. Photo: Sam Hartnett.

Are you ever disappointed people don’t react more strongly to your work?

Before I showed in art spaces, I only showed my work on the internet. I enjoyed their interpretation, [although] the comments could be really harsh because they had no background, no anticipation. They would say mean things, like I must have been sexually abused by my parents in the past. Nowadays, when people see the work in an art space they have certain expectations. If terrible things or weird things show in an art space, well that’s art.

But your videos are not so far removed from real events. You saw an old man throwing away his pristine collection of Japanese porn VHS tapes, and that inspired Dear, can I give you a hand? (2018), for instance. Another influence was the passing of a 2019 extradition law, after a 19-year-old man killed his 20-year-old girlfriend in a Taipei hotel and packed her body in a suitcase. The event was as violent and tragic as anything in your work, like the brother’s murder in ‘Judge Bunny’, one of the stories in Fables 2.

When I talk about seeing an old man throwing away VHS tapes of pornography, I immediately had a scene in my head. I dug deeper, [thought of] images, social issues, desires, and so on But when I try to explore these, I feel like many people, [even] friends of mine, feel it’s just bullshit, nonsense. They say, ‘let’s talk about something real or more practical, like where to eat.’ Sometimes people bypass the ideas behind things. People would see the murder and think it’s a typical murder case on the surface, but I think there’s hundreds of things to explore and dig deeper, even if it [turns out to be] nonsense.

When people know my work, they sometimes talk more openly to me. With certain works, complete strangers would come up to me, talk [for] 30 seconds or one minute, and say, ‘I thought you would be more weird, or funnier.’ But they are strangers to me, and I’m not here to entertain.

Wong Ping, Wong Ping's Fables 1, 2018. Installation view, happiness is only real when shared, Gus Fisher Gallery, March 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong/Shanghai; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York/Los Angeles. Photo: Sam Hartnett.

Wong Ping, Wong Ping's Fables 1, 2018. Installation view, happiness is only real when shared, Gus Fisher Gallery, March 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong/Shanghai; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York/Los Angeles. Photo: Sam Hartnett

You have a very distinctive visual style, dominated by strong geometric shapes and bright colours. How did it come about?

First I learned Photoshop in school, where they taught us how to retouch people’s faces. Nowadays everyone knows how to do it on a cell phone — I had one semester to learn it! Then I picked up After Effects in my first day job [as a tool] for post-production for movies and dramas, nothing related to animation. One day at work, I opened Illustrator and found vector graphics. I found I could use whatever colour I wanted, and I used the software to move stuff in position, [for] scale and rotation. These basic skills are what I use in 90 percent of my work — a cocktail of unprofessionalism.

I took another class that talked about colours, for advertising. How Coca-Cola uses red on black or red on white, theories about colour combination. I found it ridiculous — why limit colour? That would be boring! I understand that in advertising it could be useful, but I thought we should be free to use colour as we choose. I quit the class after the first day.

Your video Stop Peeping (2014), about a man who makes popsicles from his neighbour’s sweat, is a story of sexual frustration and living too close to others in a small apartment. Is it important to you to communicate social problems in Hong Kong?

Social issues and politics, starting out, filled up at least 50 percent of my work, but I tried my best to balance it. Now, I don’t want to talk about [political] things. It’s not self-censorship; now in Hong Kong the situation is at the edge, or over the edge. Maybe I don’t have faith in art, but I don't feel like I need [art] to reflect or make a comment on [society]. It’s too late to use art to respond to that.

Nowadays in Hong Kong we need physical, more straightforward, power to fight back. With the internet [and] social media, everyone knows the situation sucks in Hong Kong. We are not the same anymore. Many of my friends moved out. It won’t be the same in the future. It will just get worse and worse.

Is it fair to say that Hong Kongers have less freedom of expression these days?

After the huge protests two years ago, when things changed extremely in Hong Kong, and also [after the passing of the] National Security Law, you could see the effect of censorship immediately. Tension and pressure are even stronger than in the mainland. Because [the law is] new, no one knows what’s going to happen.

It's still happening today. They interviewed a hip hop band in Hong Kong that addressed social or political issues. [Then] they replaced the TV department head [with someone new who] cancelled all these interviews because they said the songs have strong words. It feels like we're kids now. We have parents. We haven't felt that way for hundreds of years in Hong Kong.

One thing I look forward to is how galleries and institutions react, and how they show works in the future in Hong Kong.

They’ll have to be creative and resourceful, I guess.

Or they will just censor themselves.

Some artists go in a more abstract direction. Beijing-based artists Sun Yuan and Peng Yu made a powerful work called “Freedom” (2009), which sees a fire hose on full blast thrash around inside a cube; while their work Can’t Help Myself (2016) is a robotic arm programmed to repeatedly mop up a puddle of what looks like blood.

I like it, I like it. But when we talk about freedom, the artist should have the choice to say, ‘oh I want to openly discuss this’, or, ‘I want to make an abstract work.’ When people talk about making work in mainland China, I feel their frustration. When they make the work, they have to do nine or ten turns to address the thing. If the artist wants people to know what they’re talking about, after the nine-turn detour, maybe 90 percent of the audience won’t get it, or it has lost its spirit.

Have you seriously considered leaving and going somewhere else?

Maybe, maybe, maybe. In Hong Kong everyone is talking about that. Especially when the British government, Canadian government, Australian government, they’re giving us more choices through visas, to stay longer as citizens, or to work. Many of my friends already moved and gave up the Hong Kong space.

It’s so sad. Hong Kong has such a special and unique culture, and you feel it strongly coming from mainland China.

It’s crazy when you think in one year, everything was destroyed. Building it up takes hundreds of years, and now, it’s just collapsed. It’s too quick.

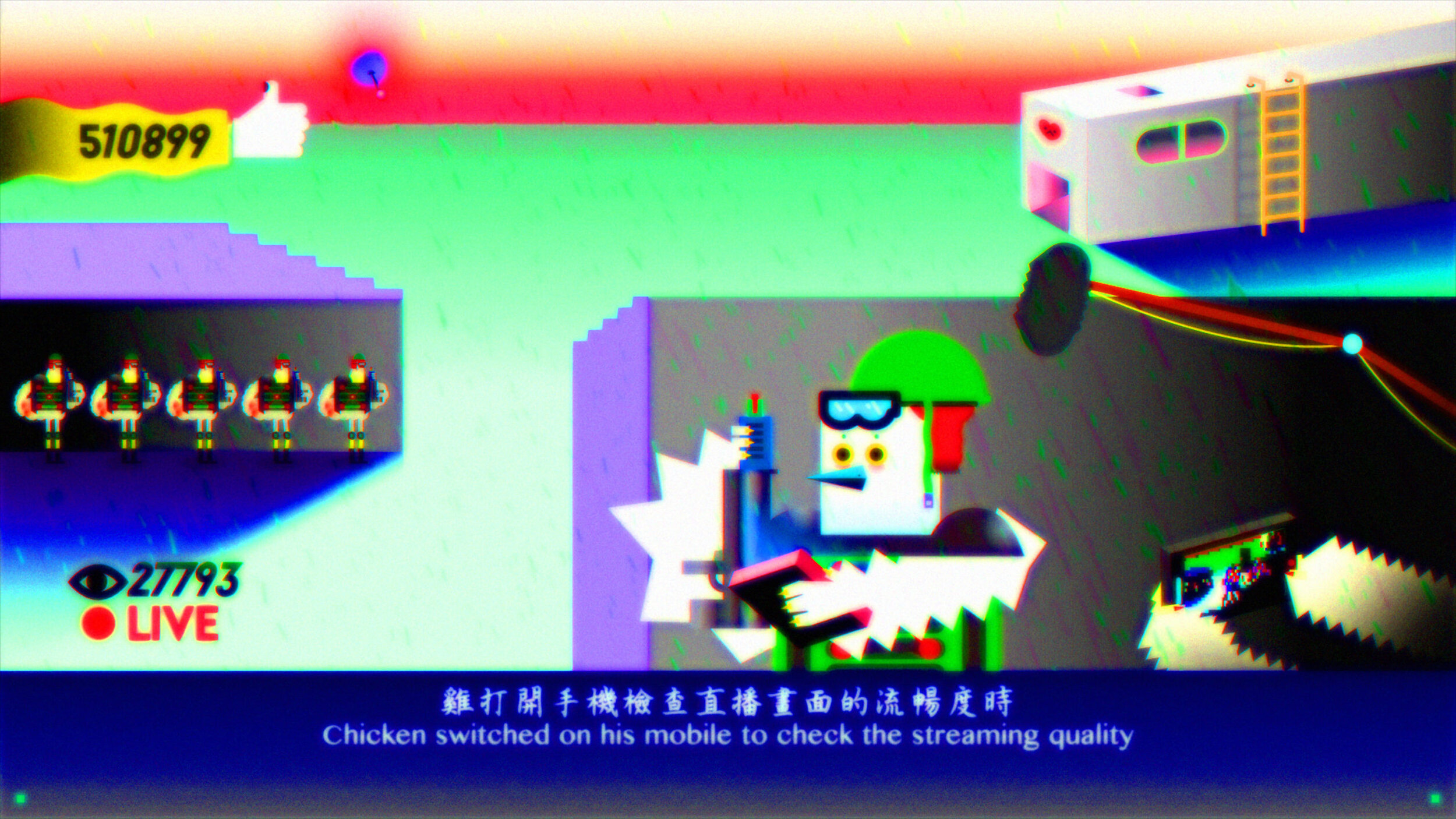

Wong Ping, video still from Wong Ping's Fables 2, 2019, single channel animation with sound, 13: 30 minutes. Courtesy of the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong/Shanghai; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York/Los Angeles

Wong Ping, video still from Wong Ping's Fables 1, 2018, single channel animation with sound, 13:30 minutes. Courtesy of the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong/Shanghai; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York/Los Angeles

Wong Ping, video still from Wong Ping's Fables 2, 2019, single channel animation with sound, 13:30 minutes. Courtesy of the artist and Edouard Malingue Gallery, Hong Kong/Shanghai; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York/Los Angeles

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Happiness is only real when shared, Gus Fisher, 13 February – 29 May 2021

Connie Brown on Simon Denny and Karamia Müller’s Creation Stories, Michael Lett, 6 August – 10 September 2022; and Gus Fisher Gallery, 6 August – 22 October 2022.