Print archive: The void and its parody: Thinking alongside Robert Jahnke’s Whenua kore, by Carl Mika

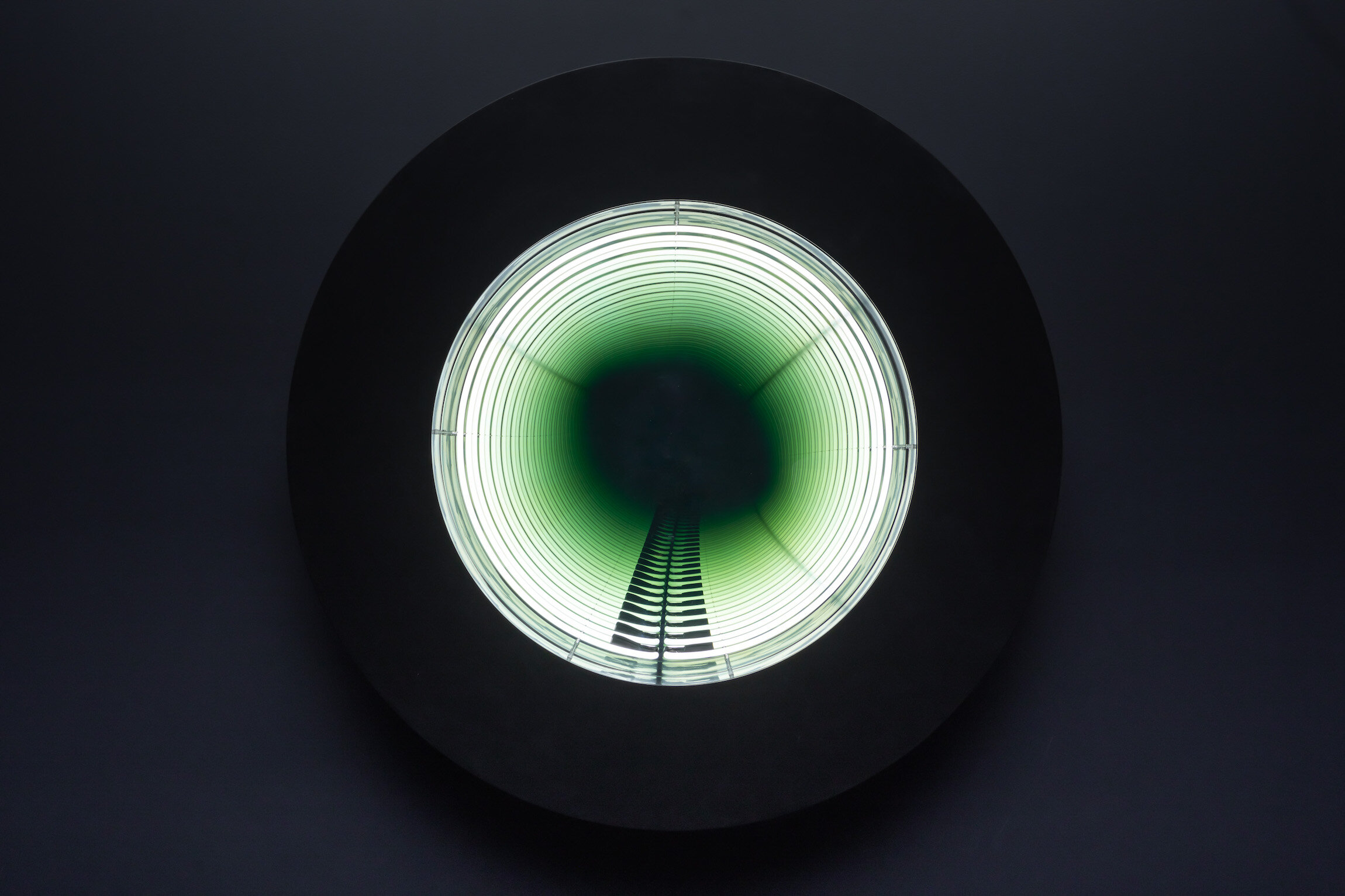

Robert Jahnke, Whenua kore, 2019, lacquer, mild steel, powder coated aluminium, neon, mirror pane, mirror, laminated glass, toughened glass and electrical components, 25 x 153.5 x 153.5 cm. Chartwell Collection, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, purchased 2019. Courtesy of Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki

Robert Janhke’s sculpture Whenua kore (2019) discloses significant possibilities for mātauranga Māori thought, raising the question of how Te Kore, or nothingness, impinges on our everyday activities. Here I will consider the potential of the void from a mātauranga Māori perspective, an approach that goes beyond simply describing Jahnke’s work. I will suggest that mātauranga Māori provides a specific octave to think and talk through Jahnke's Whenua kore, whilst putting forward parody as a device for reinterpretation and considering how the Māori academic writer is positioned in relation to the register.

The creative potential of mātauranga Māori thinking is still in the making—Te Kore, “The Great Nothingness” (among other stages of creation), brings us to reflect on our narratives and contexts. (1) Seen in this light, Te Kore is not simply a deceased relative, an ancient ancestor who happened to leave a legacy of light. It lives on independently and fundamentally as a ground that founds the existence of all things—the orientation of rock, plant, human, mountain, and even coronaviruses, towards and within the world. Specifically for the human, each entity is embedded, and has its own way of being, in-the-world. Te Kore demands contemplation and open-ended conversation, infusing everything and structuring the parameters of thought, and thus speech.

Māori academic Moana Nepia outlines the influence of Te Kore thus:

As eternity, Te Kore articulates space into which we may speak and move, or be denied opportunities to express ourselves. Moments of calamity, or uncertainty when all seems disconnected, and unsuitable must be overcome if a creative journey is to fulfill its purpose. The creative process, like a journey, may also have abrupt halts. (2)

Any mātauranga Māori thinking, then, would be speculative rather than definitive, leading us open to moments of uncertainty. This vulnerability is a potential aspect of Whenua kore. The title of the artwork is “a parody on a term most associated with the epi-centre of intense activity or change,” a locus of disaster. (3) Whenua kore could be interpreted as ‘Ground Zero’, signifying destructive change where land has been taken from Māori.

The term also creates parody by establishing another ground that cements the realms and horizons of possible thought and utterance. Jahnke has, perhaps, utilised parody to reflect a Māori way of representing a phenomenon, rather than relying on the “centrality of ‘analysis’ and importance of detachment.” (4) Here, a certain onto-epistemology is at work—both a contemplation of Māori caricature or satire, and consideration of both physical and emotional abyss.

Whenua kore may, alongside loss of land, also be about the loss of Māori thought, or at least the forcible suppression of it. In other words, Whenua kore attends to ‘ground zero,’ the destruction of Māori perception, knowledge and thought. In making this claim, I am being deliberately creative, but for some support I draw on both Royal’s idea that whenua triggers Māori thought, (5) and also Greenwood & Wilson’s conclusion that “ka tu te ihiihi/ka tu te wanawana/ki runga i te whenua e takoto nei, e takoto nei”/“... the land surrounding us/proclaims its wonder.” (6)

Taking these ideas further, I say that there is essentially no difference between whenua and whakaaro, or thought-that-unifies. Whenua, as is well-known among Māori, is both land and placenta, but through its deep relationship with ‘Papa’ it manifests as an entity that provokes us, gives rise to our problematic assertions, and then encourages us to undo them. Whenua in this instance would be one way of referring to the substance of whakaaro, of thought (or un-thought), and in that way whenua nourishes our thinking. In our colonised realities, though, we are no longer allowed to follow that line of thought, or even reflect on the possibility that whenua and whakaaro are, in fact, one.

Let us now address the parody that Whenua kore is equated with. In Māori settings, parody takes place all the time; yet, in academia, parody is permitted only if made self- conscious, only with great unease (presumably for fear it is not ‘nice’, not neat and tidy, not adhering to that conventional logic mentioned earlier). Parody, whether through destabilising an original statement, behaviour, or image, is essentially taking something off. Although Jahnke’s use of the term is a form of parody, Whenua kore is also a way of parodying, arranging the world as a profound loss of thought—and if that is true then Whenua kore becomes an approach, or method for thinking. Whether we would want the suppression of Māori thought—a ghastly, traumatic event—to form the framework for our thinking is up for some discussion, but we can conceive of it this way: Whenua kore has the potential to not only refer to that loss, but also to a spectrum of thought that puts itself into decline, or makes itself absent. It might, for instance, privilege a style of thinking that sets something up as true, then simply takes it off—parodies it—resulting in the loss that Jahnke refers to.

In returning to Te Kore more broadly, we can speculate on its relationship to thinking in this way: Te Kore, along with other ancient phenomena in the Māori world, presents a thing in the world—such as a human being—by laying the ground of its existence. That thing, in turn, presents Te Kore through its entrenchment in-the-world. A rock has its own way of being at one with the world, as does the human. For the human, contemplation is a mode of a person’s being-in-the-world. And contemplation, as we have seen, has its depths in Te Kore. A contemplative device is a destructive and creative parody.

Te Kore, in conjunction with other timeless phenomena in te ao Māori, gives things their existence and outward purpose. Te Kore presents Whenua kore both as a sculpture and an abstraction, which in turn presents Te Kore through its power to parody. In a note that sat alongside the artwork at Paulnache, the writer refers to the illusion that mirrors create, encouraging people “to physically engage with the sculpture, to sit, or move around the neon on the cylindrical platform and even walk over the illuminated neon drum; over the epi-entre or the bullseye that marks an area of land in which Māori have zero interest; the land on which the sculpture is located.”7 Yet such engagement is always going to be tentative as one enters the realm of Te Kore, which will only satirise the idea that the human self is sovereign. The human onlooker feels vulnerable as they gaze into the abyss, where the circular drum of mirrors creates the illusion of a void. In Whenua kore, Te Kore has, in effect, provided the ground of existence for mirror, human self, thought-as- unifier (whakaaro), and endless possibility to come together. All these things will, in turn, present Te Kore, and so it continues.

Te Kore provides mātauranga Māori with various registers or frequencies as much as a body of knowledge. Where speculative art and poetics exist, te reo o mātauranga Māori seems to flourish also. Can mātauranga Māori as an octave take centre stage in our academic work, though? Jahnke’s work demonstrates that the void—immediately invoked by a mirror with seemingly endless, shallow reflections of darkness—is present in everything. It demonstrates that Te Kore can never be sidelined, even when we are trying to be coolly eloquent. The infinity of the mirror and the permanence of Te Kore both teach us that we need to think beyond the rational, and that we should prepare to be ‘sent up.’

Te Kore moderates the world of clarity, commonly known as Te Ao Marama. When we go to act, we are invited by Te Kore to emphasise what is absent, summoning our lack of confidence or fallibility. Te Kore is not to be done away with easily; it simply reveals an underlying angst. It exposes the jugular that our logical certainty rests on. In a sense, it casts aside our own certainty and invites us to participate in the abyssal Ground Zero of existence.

Footnotes:

(1) “Robert Jahnke: Ata tuarua,” Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki. aucklandartgallery.com/explore-art-and- ideas/artwork/26905/ (accessed 7 February 2021).

(2) Moana Nepia, Te Kore: Exploring the Māori concept of void, PhD thesis, Auckland University

of Technology, 2012, 70.

(3) “Prof. Robert Jahnke, James Ormsby at the Auckland Art Fair,” Paulnache, April 2019. paulnache.com/aaf2019 (accessed 12 January 2021).

(4) Cohen, M. 1999 101 Philosophy Problems: Second Edition, London and New York: Routledge.

(5) Te Ahukaramū Charles Royal, “Whenua—how the land was shaped,” Te Ara: the Encyclopedia

of New Zealand, accessed 18 January 2021. teara.govt.nz/en/whenua-how-the-land-was-shaped

(6)Arnold Manaaki Wilson and Janinka Greenwood, Te mauri pakeaka: A journey into the third space (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2006), 89.

(7) “Prof. Robert Jahnke, James Ormsby at the Auckland Art Fair,” Paulnache.

Writer biography: Carl Mika is from Tuhourangi and is an associate professor in the Division of Education, University of Waikato, New Zealand. Previously, he worked as a criminal and Treaty of Waitangi lawyer, librarian, and research contracts manager. He now works almost entirely in the area of Māori thought/philosophy, with a particular focus on its revitalisation within a colonised reality. Committed to investigating indigenous notions of holism, Carl is currently working on the Māori concepts of nothingness and darkness in response to an Enlightenment focus on clarity, and is speculating on how they can form the backdrop of academic expression. He is interested in current debates on crossovers between Māori thought/ philosophy, education and science. He is Director of Centre for Global Studies, University of Waikato and adjunct professor of RMIT.

This article appears in The Art Paper Issue 00. Please buy or subscribe to read more.

(limited edition brochure)

Issue 00 celebrates artists who live or exhibit within Tāmaki Makaurau (Auckland), Aotearoa (New Zealand). Produced in conjunction with the Auckland Art Fair 2021, published by Index.

Featured artists: Conor Clarke, Owen Connors, Millie Dow, Ayesha Green, Priscilla Rose Howe, Robert Jahnke, Claudia Jowitt, Robyn Kahukiwa, Yona Lee, Zina Swanson, Kalisolaite ‘Uhila.

Contributors: Dan Arps, Julia Craig, Erin Griffey, Susan te Kahurangi King, Shamima Lone, Victoria McAdam, Robyn Maree Pickens, Meg Porteous, Lachlan Taylor, George Watson, Victoria Wynne-Jones.

Specs: 56 pages, 23 x 26 cm (folded vertically)

Julia Craig on Owen Connors’ egg tempera paintings.