Dreamy Era

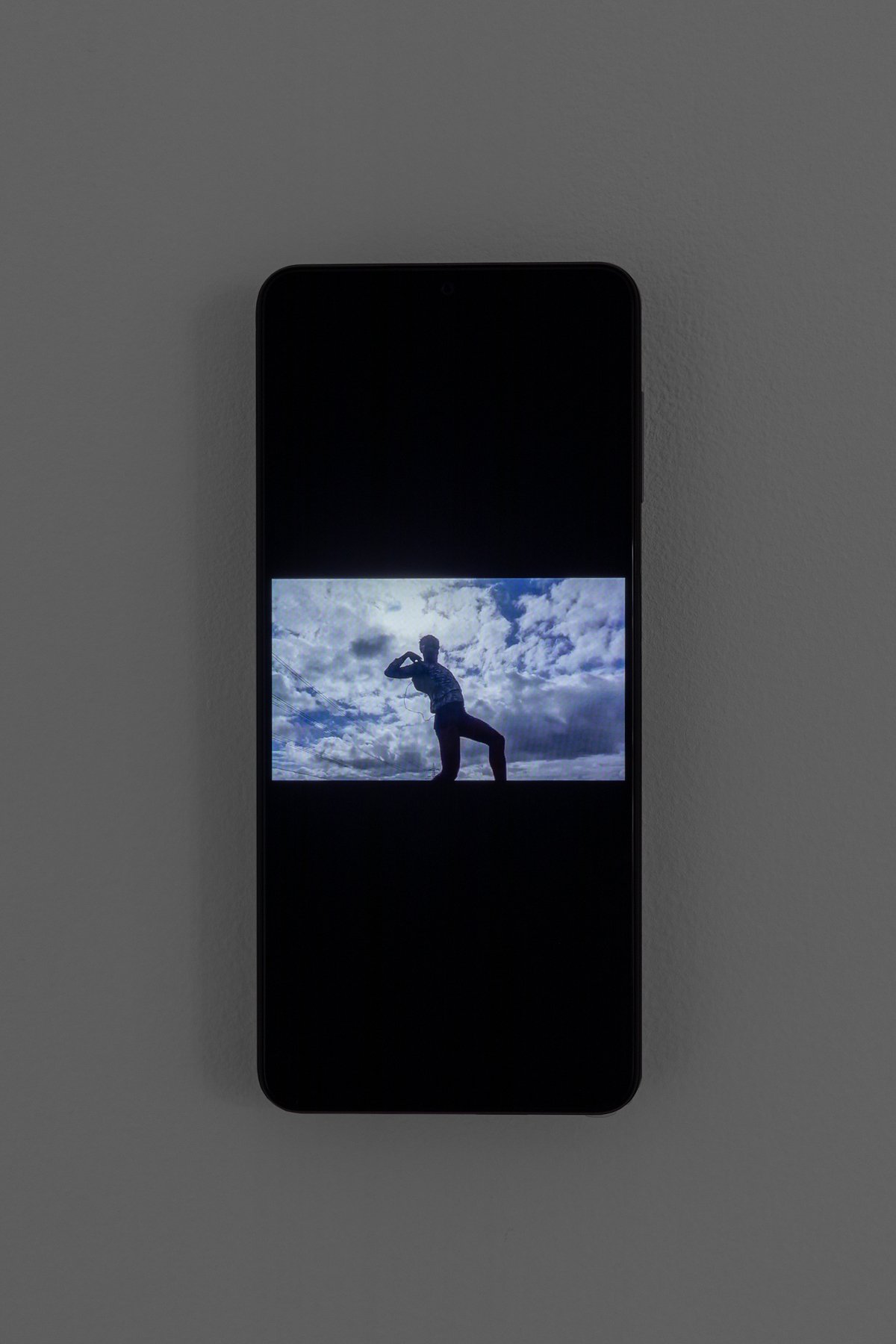

Moya Lawson on Sione Monū’s Volver—originally commissioned by Robert Heald on the occasion of the exhibition. Sione Monū, Vape, 2018, digital video, 59 sec

A couple of weeks ago, Sione Tuívailala Monū made an Instagram-story tribute to their recently retired iPhone X:

Thank u iPhone X for 5 years of laughs and tears and art and sex I downloaded so much of my joy n trauma n memories into u I’m so grateful. Ur part of a long line of banged up but ever loyal mobile devices that made me into the leīti* I am today so thank u babes xx

In the photo, the phone lies like a pietà in Monū’s hand, its glass skin smashed. It’s been through the wars.

Volver presents seventy-eight videos split across ten Samsung A22s. Like its Spanish translation, Volver returns. The compilations on each phone have been selected by Monū, and span five years between 2015 and 2019. Made amid the flux of regular travel between Tāmaki-Makaurau, Sydney, Melbourne and Canberra, the exhibition captures the beginnings of Monū’s now distinct filmic language.

All of the videos were shot and edited on smartphones. They are no more than a minute long, some are as short as ten seconds. Their pace varies. Some burst with theatricality, others unfold slowly, like a dream. Monū pushes the smartphone quality beyond what it’s used to. The videos can feel lo-fi but incorporate sophisticated filming techniques. Images might slip into a second of pixellation, triggered by a sunburst or movement, while being part of a polished composition of story-board shots.

Filmed in homes, workplaces, and family functions, museums, parks and malls, bus stops and laundromats, Monū is rarely in the same place twice. They move placidly through these scenes, complemented by ambient noise, casual conversations, trilling Spanish guitar, alternative R&B or mournful violins. Family and friends feature as blasé extras or giggling collaborators—and give the impression that they’re used to it.

Monū directs, shoots and stars in all of their videos. Usually they’re before the camera, but sometimes they’re rustling behind it. They are the central, connecting subject of their work. Doe-eyed and acting unawares, Monū performs an ad-lib, whimsical story-telling about their life and the people and places that form it. It’s an intensive labour of love, which is made plain across the sheer number of videos in Volver.

Perhaps unwittingly, Monū’s video practice emerges from a range of technological and cultural shifts of the last decade. In 2010, Apple introduced the first front-facing camera in the iPhone 4. This seemingly benign development would transform the way we looked at ourselves. In simple technical terms, you could see yourself in your screen as you took your photograph and could compose and focus it perfectly. The murky, over exposed bathroom selfie was now a thing of history.

Three years later, Monū gravitated to Instagram’s newly introduced video feature, which allowed users to post videos at a maximum of one minute in length. At the time this was restrictive for most people who struggled to condense their experiences into sixty seconds. For Monū, however, it offered a window of opportunity. Post by post, they began to explore what they could capture and share within these parameters, often turning to the people around them as their muses. They built characters and invented narratives for themselves and their collaborators, conflating documentary and make-believe.

On their Instagram (@sione_has_doubts), Monū’s posts often arrived amid a succession of white squares—which would disrupt and confuse your Instagram feed but also caused you to click through and look. On their profile, these squares created negative space around the images, as if the posts were mounted on a white wall. Scrolling down would connect posts to earlier ones, like adjoining rooms. Sometimes these arrangements were overlaid with scribbles, emojis and drawings, connecting across the squares like a site specific installation. The IG as white cube.

The mounted phones thus reference where you’d usually encounter this kind of work by Monū, in a palm-sized screen. By 2019, Monū’s online following had expanded beyond their immediate friends and family. People who didn’t even know them (like me) were drawn to the eclectic and entertaining way

Monū shared their world(s), and many related to them too. Monū constantly twists the weak divides between what art is and what it apparently is not, plucking at these questions with an entertaining nonchalance. They co-opt and reinvent Instagram’s restrictive aesthetics, making portraits borne of the entangled relationships we’ve formed with our smartphones, social media, and image making.

In June 2021, The New Yorker reported that “We All Have ‘Main-Character Energy’ Now”—after our release from being cooped up and collectivised (against our will) by the pandemic. (1) “Main-Character Energy” describes someone who acts like they’re the main character of the story which is their life. It’s been used as both an insult and a call to action: on the one hand, embodying the apparent narcissism of our social-media age; on the other, insisting we lead our lives more meaningfully. As one viral TikTok voice-over says, “You have to start romanticising your life. You have to start thinking of yourself as the main character. ’Cause if you don’t, life will continue to pass you by.” (2)

Monū’s videos predate this term by several years, but they certainly epitomise its energy. Their head tilts out the window of a car in Caution (2019) under a full-face reflective visor which shudders in the wind. Monū and two friends are framed, pensive, against Constable-esque clouds in Canberra Tourist (2018). In Mangere bridge rain (2017) Monū leans back against the railing, head back, resigned to the weather’s pathetic fallacy. While they’re certainly playful, there’s nothing cynical or mocking about any of these gestures. Alongside the stagecraft, Monū’s videos are punctuated by deeply intimate, moving and ecstatic moments, too. They’re honest and uncompromising.

Sione Monū, Clones, 2016, digital video, 45 sec

Sione Monū, Doppelgänger, 2016, digital video, 28 sec

Sometimes, however, Monū convolutes their role at the centre of their video practice. They frequently peer at their appearance in mirrors with existential melodrama. In three videos, Doppelgänger (2015), Doppelgänger (2016) and Clones (2016), they appear in double: bumping into each other as bemused strangers in a bus stop; unhitching the safety lock on the other in a wheelchair; confronting a third clone in their back garden. Other videos verge further into absurdity, where crude animations of snakes and butterflies seem to interrupt Monū’s enacted routines. Unsettling the waters of Narcissus’s pool, they take a sidelong glance at the very individualism which informs them.

Monū’s sense of self is better attributed to their life-long devotion of film. Volver is in fact the title of a Pedro Almodóvar film, one of Monū’s favourite directors. It sparked Monū’s love of film at a young age. Starring Penelope Cruz, Volver is a forceful exploration of maternal relationships. It brims with fiery Latin emotion, spirit and superstition—and Monū’s own films bear unmistakable similarities. But Monū doesn’t stop there, their references in Volver (the exhibition) also include Damien Chazelle’s La La Land, Park Chan-wook’s The Handmaiden, Charlie Kaufman’s Synedoche, New York, and Pride and Prejudice (the one with Keira Knightley, of course). The Internet and social media have no doubt helped build their expansive repertoire. Monū’s interpretations of film genre are like caricatures encapsulated in a minute—soap, Animé, experimental, mumblecore—establishing a mishmash vernacular for themselves.

Every new social platform signals a wave of new content to engage with, adding another element of intricacy to our interactions. Every new face filter or emoji release expands the lexicon we use to communicate. Our Instagram or Facebook or Twitter feeds form our own alternate universes, where current affairs, relationships and interests collide and mix. Language is personalised and layered, like text over filter over image. These worlds appear before us like dreamscapes, unpredictable and cryptic. Monū’s videos both draw from and live through these contexts, gleaning diverse inspirations, spurred on by the energy of globalised cinema. With roots put down on either side of the Tasman, and across the Pacific Ocean, they harness the malleability of their medium(s) to convey the complex conditions of living in diaspora. These expressions travel, too, finding connections across oceans. Monū’s videos encompass a viewpoint which is sovereign, networked and fluid.

Monū’s practice is therefore a journey of self-discovery as much as self expression. It is an ode to love, family and friendships. Their videos exist and unfold in their own universes and are often beyond our full comprehension. We’re absorbed by them anyway. Thinking back to the TikTok voice-over, perhaps Monū is answering the call of “romanticising your life.” They channel the elated feelings you have in the Uber home after sitting in a great film for a few hours, or how a new song can make your surroundings look like a movie set—suggesting that these states are full of creative potential. Monū proposes a way to look at the world differently, savour it, escape it, or indulge in its multiplicity.

Footnotes:

*a Tongan word to describe the third gender.

(1) Kyle Chayka, “We all have ‘Main Character Energy’ Now,” New Yorker, June 23 2021, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/infinite-scroll/we-all-have-main-character-energy-now.

(2) Ashley Ward, (@ashlaward) “A Moment Apart – ODESZA,” May 27 2020, https://www.tiktok.com/music/A-Moment-Apart-ODESZA-6831269889798441733.

Sione Monū, Home, 2019, digital video, 59 sec

Sione Monū, Box hill hospital, 2019, digital video, 38 sec

Sione Monū, Recovery PART FOUR, Dildo, Factory, Gangz, Going thru it, Foggy glass, Home, 2016 – 2019, digital videos on Samsung Galaxy A22, 6 min 13 sec

Sione Monū, Gangz, 2017, digital video, 59 sec

Sione Monū, Recovery PART FIVE, Wharf, Box hill laundromat, Butter chicken, Nelly furtDO, Laundromat, Beach contemplation, 2016 – 2019, digital videos on Samsung Galaxy A22, 6 min 49 sec

Sione Monū, Recovery PART SIX, 2016, digital video, 1 min

Sione Monū, Recovery PART SEVEN, 2016, digital video, 53 sec

Sione Monū, Auckland museum, 2016, digital video, 52 sec

Sione Monū, Snickers pods, 2018, digital video, 57 sec

Sione Monū, Leitī, 2016, digital video, 1 min

Sione Monū, Auckland city night time, 2017, digital video, 1 min

Sione Monū, Tree, 2016, digital video, 29 secTree, 2016, digital video, 29 sec

Sione Monū, Auckland city night time, Lil sis, Box hill, Recovery PART SIX, Auckland city, Aunty Lisa, Mangere bridge rain, Box hill laundromat night time, Canberra tourist, 2016 – 2019, digital videos on Samsung Galaxy A22, 9 min 43 sec

Sione Monū, Snakes in the grass, 2018, digital video, 31 sec

Sione Monū, Volver. Installation view, Robert Heald, Wellington, April 2022

Sione Monū, Volver. Installation view, Robert Heald, Wellington, April 2022

Sione Monū, Volver. Installation view, Robert Heald, Wellington, April 2022

Julia Craig on Owen Connors’ egg tempera paintings.