Art Criticism: An essay in eight parts

Fergus Porteous on Shiraz Sadikeen, Ends; Coastal Signs, 15 September - 22 October 2022.

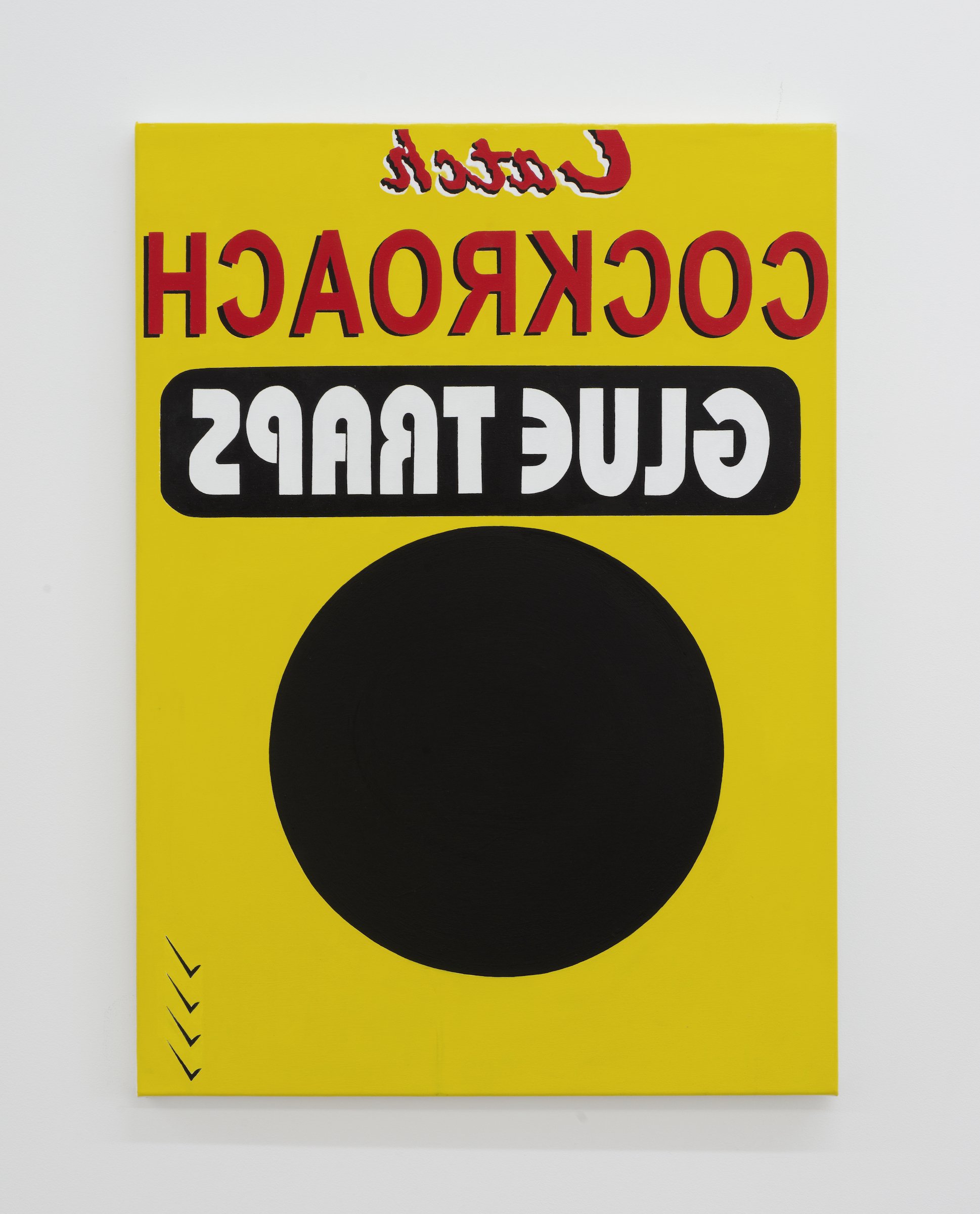

Shiraz Sadikeen, Glue Traps, 2022, acrylic on canvas, 83 x 58.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Coastal Signs. Photo: Alex North

1. Introductory remarks

Shiraz said we’re deluded if we think art is going to effectuate some kind of positive social change. I probably shouldn’t quote him out of context, and when he’s been drinking, but he’s right. His second show at Coastal Signs, Ends,(1) might appear as esoteric and repetitious as any of his previous. Twenty works, comprising six large paintings, various readymade objects that include components from a deconstructed clock, a dollar coin filled with bone wax, and yet more of his grimaces cast in resin. A number of the works are reappropriated from previous shows, a comment on repetition and stagnation in art and culture generally, of uroboric lethargy. And for the first time, a self-portrait, though not in name.

For the longest time I’ve been complaining that I don’t see enough of Shiraz in his work.(2) The art community shouts me down when I bang this drum. “You don’t know anything about art,” they say. “Go back to your books: with your unreliable narrators, your grammar, etymology and narratology. Finish your novel.” Well, I refuse. To explicate Shiraz’s tight chiasmic puzzles is, to my mind, unnecessary, and plays into his hand. Don’t pull the threads. Instead I’ll evaluate the artworks on the level of form, for its strategic use of devices like narrative voice, point of view, delayed disclosure, reader response. What I have to say about his work is neither difficult nor contentious; the only merit I should like to claim for it is that of being true, at least in parts.

2. Clocks

Clocks have long been my favourite symbolic object. Shiraz and I met at the turn of the millennium as boys on the cusp of puberty. My initial attraction to him was, I suppose, fringed with envy for his close friendship with another boy, Zaryd Wilson. I recall deciding quite consciously that we were destined to be old friends, Shiraz and I, so I prevailed upon the two wherever possible. He and Zaryd lived along the walk home from intermediate which became the predicate for our budding relationship. I confess feeling left out in the beginning: I was lanky and stooped from an early growth spurt, and their diminutive pairing didn’t accommodate my loping gait. Eventually Zaryd fell away, and Shiraz and I remained close during high school through our affiliation with the art department where my mother was a teacher.

3. Glue traps

The centrepiece (3) of his show is a faithful rendering, in paint, of the packaging for a glue trap for cockroaches, but inverted so that the image faces away from the viewer. He does this a lot, the reverse image. Someone suggested that it’s a nod to right-to-left text in Islam but I’m not sure. I discovered the same product at a dollar store on Albert Street and in comparing the parent to its reproduction found several differences that affect my interpretation. (4) The piece introduces a kind of leitmotif: the black circle, seen also in the clock face. A monadic dot. Eschewing the latent Islamic allusions, I asked him what he thought the circle meant. He suggested that to construe the image the right way up would be to implicate the viewer, or perhaps the artist, within it. He described the circle as black, though he could have said blank. I may have misheard.

What people find frustrating about him, I venture, is this ambivalence he appears to have to art and the art world in general. I’ve heard people describe this silence as an affectation, that he’s aping some artist paradigm, but they’re wrong. Shiraz doesn’t ape, all the more infuriating to his critics. I recall when he first began to forgo the expectations of polite society. After university he moved to Melbourne and lived with his parents in the suburbs and worked a supermarket job. From what I gather, he spoke to no one. Took on a type of defiant silence. Thought deeply. When he returned to New Zealand it was with a confidence in himself as a shadow, a ghost, with a sense of abandonment and disregard. I’m mythologising, but this was the noticeable effect: he no longer pursued small-talk and would sit in protracted silence with no qualm, quite disconcerting for new acquaintances. People fall silent when he does speak. He’ll say things like: “the human being is still time’s carcass” (5) and we nod as if we understand.

Shiraz claims to not remember, but glue traps were my Granny’s preferred means of pest control. (6) She hung them from the ceiling of the kitchen where they blew about in the hot Waikato wind like party streamers—yellowing strips of glue paper covered in flies. Granny and I fought terribly about their use in the beginning. I was incredulous as to their efficacy, relying entirely on the random chance that flies would alight there, but the longer I lived on the farm the more rational it seemed. An inexorable proliferation of flies foments venomous anger, and I found myself looking forward to the mornings before work when I leaned against the kitchen sink, watching the newly caught flies await starvation while I finished my porridge.

4. Debates on art

Which leads back into my main point. It was perhaps four months ago that I first drunkenly debated Shiraz about his choice, as an artist, to remain, as it were, invisible. A problem, I argued somewhat inarticulately, that evinced a neglect for the narrative potential of his work; specifically, in the relationship of the work to its implied author. I’d been repeating this sentiment a lot and not just to Shiraz, but I’m as yet unsure whether it was a genuine feeling or a kind of flailing because I don’t know much about art. I guess I’m wedded to a literary frame. Maybe I was being antagonistic. Or maybe I was trying to get him to admit he’s not a very emotionally available person. In any case it was mean-spirited of me, but I can speak to him like this because we share such a deep and loving familiarity. He would cringe at this sentiment and I know he thinks I’m a fool but I don’t care. Friendship is when you see another’s flaws and accept them anyway. I’ll happily be his fool, no matter to me.

5. Uberrima fides

I visited Shiraz in his studio in August where I first saw the painting Lifetable, in which the eponymous table has been flipped so the viewer looks through the numbers as if through a window. Life tables, also known as mortality tables, are produced by Statistics NZ and used by actuaries to calculate premiums for life insurance. (7) I asked him to explain the work, which he seldom does. If you push him too far he withdraws—a cat-like quality. He only ever moves slowly, speaks with a laconic drawl. He dresses in black. Long sleeves, trousers. For the most part his body remains invisible, apart from his face and his slender, slightly veinous hands. It’s hard to describe his unknowability without slipping into whimsy over his whorls of jet black hair that fall lank and glossy on either side of his shapely face. He’s an objectively beautiful person by anyone’s measure.

Left alone in the studio, I stared at Lifetable until the reversed Arabic numerals appeared to detach themselves from the white background and become shimmers of lilac, gold and brown. Walter Benjamin said there is no document of civilisation which is not at the same time a document of barbarism, no truer than in the accounting of labour, debt and human capital. I have been known to make the argument that good art is always fundamentally about death, but I’ve revised that to the assertion that good art is always aniconistic. (8) For a long time I thought Shiraz eschewed aniconism—his work relies on explicit signifiers, operating like an index, a codex—but that’s misdirection. All his meaning is right there in the surface, and he often says interpretation only ever goes beyond the given in order to return to it. (9)

6. Anxiety

Henri Bergson described comedy as watching a room full of dancers with your ears blocked—the comedy of repeated meaningless actions, of grey routine. Shiraz is often repeating himself, but that’s the point, because, as he put it: so is the thing he’s supposed to be sublimating. A popular work in his previous show (replicated for Ends) was a pink photocopy of the cover of the Beach Boys’ album Surf’s Up, a painterly rendition of The End of the Trail, a sculpture depicting a weary American Indian hanging limp as his weary horse comes to the edge of the Pacific Ocean. One local critic posited that the work might have been an attempt at self-portraiture; (10) based (I assume) on the erroneous assumption that Shiraz is Indian: he’s Sri Lankan. Perhaps such mis-recognitions are inevitable. It’s been noted that Checkhov’s play The Cherry Orchard has two loaded firearms that are not fired—so too, perhaps, Shiraz’s work contains actions never completed or never even commenced.

If there is a self-portrait in Ends, it is Guts; a primitive scribble of a defecating worm, apparently afflicted by severe intestinal anxiety. The worm’s distress is overtly comic, but I’d argue that it doesn’t exclude pathos. Tragedy proper is only ever got at through comedy. In one manner of speaking there would seem to be a little of Shiraz hidden in the painting of the worm, but in another manner of speaking there is no worm at all, only shapes on a canvas.

7. On magic

So if you’ve been paying attention, you’ll know there is no ‘putting yourself in’ except by trickery and illusion. ‘Show don’t tell’ is the doctrine of literary workshops everywhere, which begs the question: how does one show anything with words? There is only telling. Shiraz never tells, especially when there are people listening, and nobody asks an artist, or a magician, to explain his tricks. (11) When we were sixteen he told me to read about the practice of fractional reserve banking, where banks use debt and leverage to literally conjure value out of thin air. If there’s any magic apparent in his work it’s in a one dollar coin, drilled out and filled with bone wax, gallerised and conceptually priced at $2,000. I tried to argue that his most recent show is democratic in the sense that all of his meaning is immanent, highly available given appropriate engagement, but I’ve had to eat those words, because trying to explain what he’s doing to anyone without an arts degree draws blank looks and incredulity. His work desires and directs its own critical interpretation as a kind of catechism, a shibboleth for the cultural class. I hear his show is selling well. The key to proper misdirection is that the audience is unaware of it.

8. End

The evening before Ends opened we went for a walk in the Hunua Ranges. The air is clearer up here, I said. Shiraz agreed.

We were starving by the time we got back to the car. We drove home down Ponga Road with the sun a red strip along the horizon and the city twinkling into the distant blackness.

Like a painting, I said, and Shiraz nodded. He lightly drummed a beat on his legs. What shall we get for dinner? I asked.

Hmm, he said. I really feel like a pie.

The air rushed against the windows.

You don’t look like a pie, I said.

Footnotes:

[1] I won’t disambiguate the various available meanings of the title here, however, I will say my preferred interpretation is an unusual though not entirely unconventional usage, as a verb in third person present meant to indicate termination of some continuum, or, as an utterance constative of the phrase: ‘this ends now’. I maintain that it would have been better with a ‘z’.

[2] I arrived at this idea after a specific episode in March: From the windows of my apartment, on the corner of Anzac Ave and Beach Road, I have a panoptic survey of the street below, and it was on a cool morning that I spotted the artist in question, Shiraz Sadikeen, walking toward the city on the opposite footpath. The shadow of his torso, head, and arms trailed behind him like a cat, starkly projected onto the white hoardings of a construction site beyond. I swung my casement window open wide and waited to see if he would look up and see me. He didn’t, and nor did I truly expect him to. He knows where I live but I suspect he pretends to forget. Poised to call his name, I was distracted by a hacking cough from the street below. I leaned out to see a bearded man shuffling slowly down the road in jandals. The man spotted a cigarette butt on the ground, picked it up, brushed it off and pocketed it, then took a few more steps into a rhombus of sunlight. As if in supplication he turned his palms out, threw back his head, tottered slightly, then smiled. I watched him for a moment then threw him a cigarette. The man’s head tracked it as it dropped past his face, and it landed on the road nearby. There was a long pause, then the man stooped to pick it up, placed it in his mouth, sought a lighter with knowing fingers from his jeans pocket, cupped his hands and lit it. He never looked up to question where it had come from, he just stood there smoking it in the sunlight. Remembering why I had been standing at the window in the first place I looked back to see if Shiraz had seen but the street was empty. He was already gone and the white hoardings of the construction site burned white in the morning sun.

[3] In the writer’s opinion.

[4] The four ticks in the bottom left of the frame are actually placed in satisfaction of the following advertorial claims: poison free, easy to use, safe, now baited. The black circle contains a photorealistic image of a cockroach, perhaps an explicit criticism of the art world, and by extension, you, the reader of this essay.

[5] Shiraz Sadikeen in conversation with the author, referencing Karl Marx, The Poverty of Philosophy (1847).

[6] Late in 2012 he came to stay with me on Granny’s farm, near Matamata, where I worked as a roofer. We climbed Wairere Falls and took MDMA; we sat beneath a rock wall, at the edge of the glistening stream. A natural dam created a pool beneath the branches of a native beech. We hung our legs over the bank and I could see the bottoms of his feet reflected in the whorling surface. And in the evening we walked to the back of the farm and threw clods of dirt into a large hole in the gathering darkness, all around the cows huffing and lowing in the dark. We listened to Beethoven and chain smoked cigarettes in the easy chairs by the window while Granny leafed through her Listener. I wouldn’t say we talked much, Shiraz and I. He was in what you might describe as a period of transition. We relaxed with typical rural pastimes: bought corn and asparagus from the honesty box and pet the bobby calves before they went to the works. We wore gumboots and smoked weed in the pine trees beside the raupō. It was nice to see a warmth in him again. Shiraz still seemed sad but he was also beyond it somehow, I imagined a sort of acceptance. Perhaps that’s my projection, though. He really just doesn’t talk that much.

[7] Under a contract for insurance a sum of money (a premium) is paid by the insured in exchange for the insurer assuming the risk of paying a larger sum upon a given contingency. In life insurance the contingency will be the duration of human life. Actuaries set premiums at a level sufficient to yield a profit and for this purpose they use life tables (also known as mortality tables) that express patterns of mortality within a population during a given time period.

[8] I’m using the word figuratively, obviously.

[9] Artist’s own words.

[10] John Hurrell, “Sadikeen at Coastal Signs,” Eyecontact, 15 July 2021, accessed 10 September 2022.

[11] Shiraz introduced me to the late magician Ricky Jay. Primarily a card-smith and sleight of hand artist, Jay’s shows were conversational and digressive, following a through-line that is ostensibly didactic, revealing tricks, while revealing nothing at all. In Ricky Jay and his 52 Assistants, Jay quotes Bernard Shaw: “Every profession is a conspiracy against the laity.”

Shiraz Sadikeen, Plume, 2022, acrylic on canvas, incense 20 x 25 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Coastal Signs. Photo: Alex North

Shiraz Sadikeen, Why I fight (communism), 2022, pamphlet, card, bone wax, 13.5 x 8 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Coastal Signs. Photo: Alex North

Shiraz Sadikeen, Succession, 2022, modified clock movement, washer, deadbolt, 6 x 6 x 2 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Coastal Signs. Photo: Alex North

Shiraz Sadikeen, Washer, 2022, dollar coin, bone wax, 2 x 2 x 0.2 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Coastal Signs. Photo: Alex North

Shiraz Sadikeen, Wageform, 2022, MDF, acrylic, matte medium, 20 x 24.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Coastal Signs. Photo: Alex North

Shiraz Sadikeen, Untitled, 2022, bone wax, wall dimensions vary, 3 x 11.5 cm overall. Courtesy of the artist and Coastal Signs. Photo: Alex North

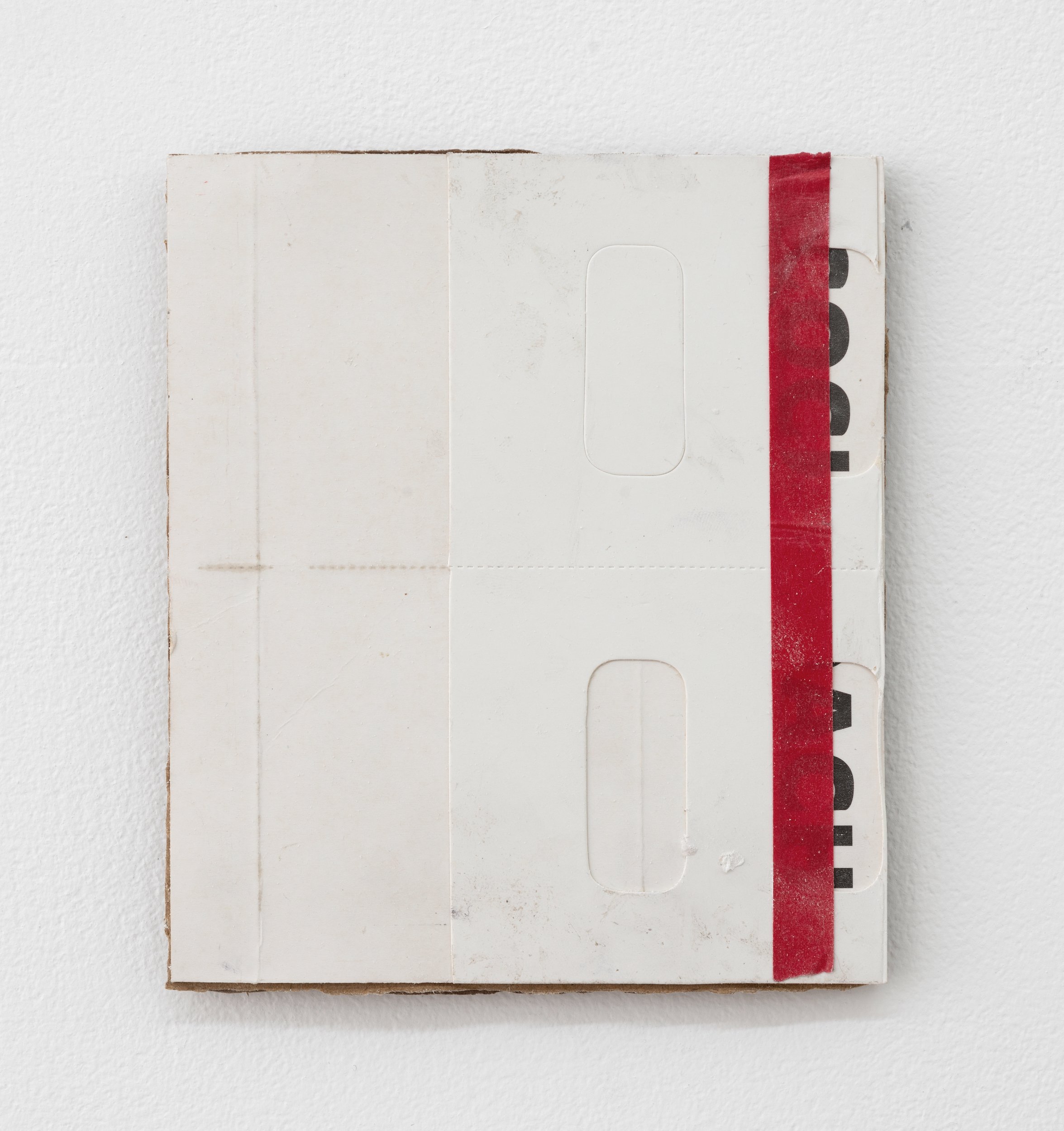

Shiraz Sadikeen, Catch Cockroach, 2022 cockroach traps, card, 13 x 15 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Coastal Signs. Photo: Alex North

Shiraz Sadikeen, Pits, 2022, six date pits, dimensions vary. Courtesy of the artist and Coastal Signs. Photo: Alex North

Shiraz Sadikeen, Geist (Ends), 2022, cast resin, bone wax, 9 x 7 x 1 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Coastal Signs. Photo: Alex North

Shiraz Sadikeen, White Spirits, 2022, acrylic on canvas, 83 x 58.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Coastal Signs. Photo: Alex North

Installation view, Shiraz Sadikeen, Ends, Coastal Signs, Tāmaki Makaurau, September 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Coastal Signs. Photo: Alex North

Fergus Porteous on Shiraz Sadikeen, Ends; Coastal Signs, 15 September - 22 October 2022.