Weighted Yet Free: Marlee McMahon's Heavy Kite

Francis McWhannell on Marlee McMahon's latest series of artworks, currently on view at Visions.

This text has been independently selected by The Art Paper and published as part of our "Collected Essays" series, courtesy of Visions.

Marlee McMahon, Heavy Kite. Installation view, Visions, August 2021. Photo: Sam Hartnett

A heavy kite is a complex construction.

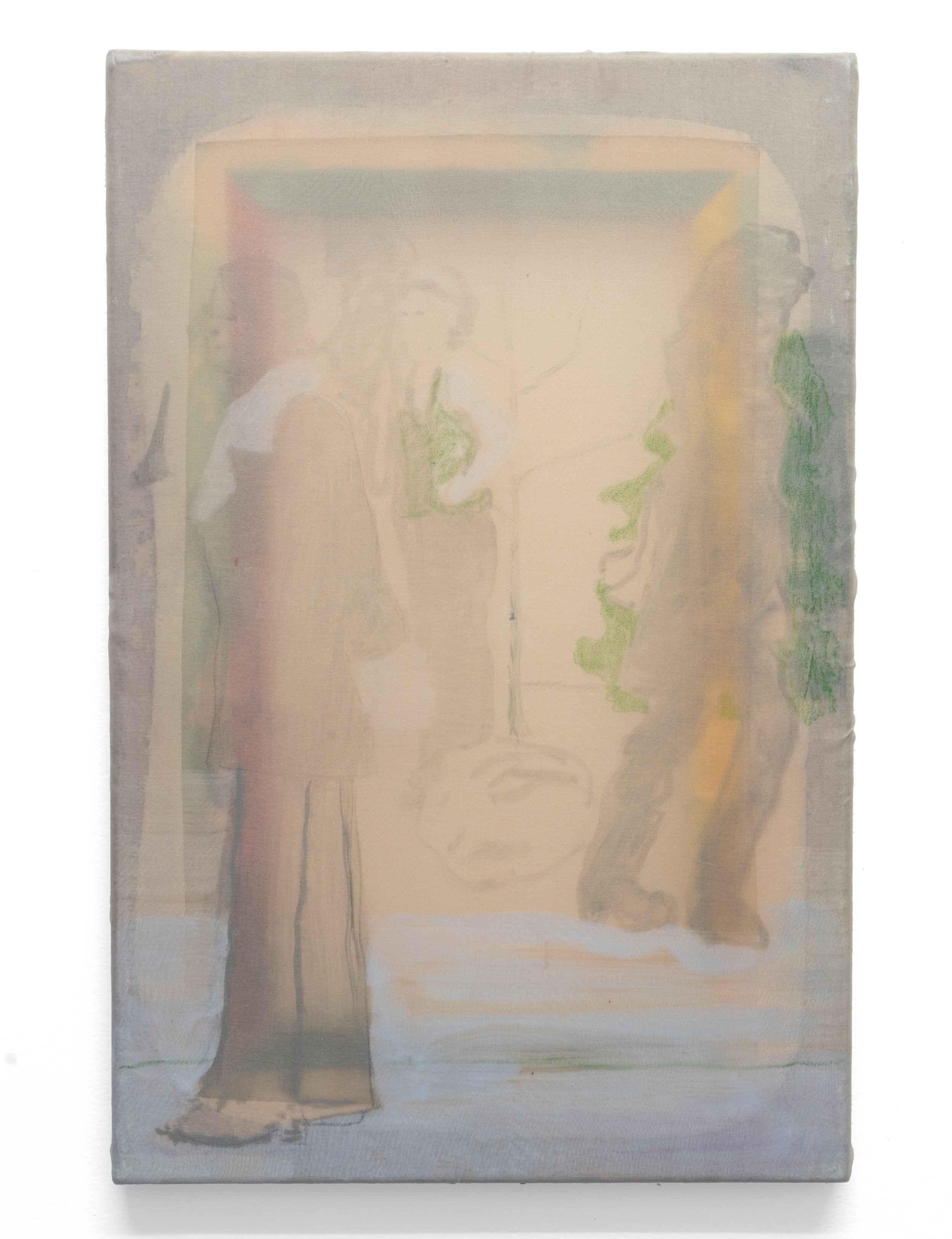

There is a warmth and softness to Marlee McMahon’s Heavy Kite, a consequence of materials and methods as much as colour. The artist speaks of wanting to shift her practice, not radically (the graphic strength associated with earlier works persists), but meaningfully. She has utilised more curves, opted for oil paint over acrylic, and moved away from masking tape, which limits her ability to consider a work as a whole and can encourage retreat into familiar compositional strategies. She speaks of wanting to ‘reground painting’, to create opportunities for greater experimentation and spontaneity. Forms in one of the first works made for the show, Paper Slide, derive from a paper collage. McMahon moved the structure about the canvas, feeling for pictorial rightness. The resulting painting captures something of the delicacy of paper. There is a sense, too, that the elements remain unfixed. One almost wants to reach out and push them around.

A heavy kite takes time to ascend.

Other works took cues from a series of small oil paintings—themselves exercises in improvisation—produced by McMahon during a lockdown earlier this year. A motif from such a study appears in Slots. Picked out in red, it has been used as a sort of tile; copies frame and seem to overlap the dark central rectangle. McMahon’s process is deliberate, her compositions the result of both intuition and calculation. She outlines and adjusts. Quick decisions are refined, enough to stabilise, not enough to stultify. Edges are demarcated with a fine brush. Planes of colour are carefully developed. Days of drying time are allowed, so that the hand-hewn forms will be maximally clean and consistent. Some are ultimately painted out. Their contours remain visible through the upper layers, like pentimenti ghosting pictures by ‘old masters’, like veins swelling beneath skin.

A heavy kite dances among the clouds.

McMahon speaks of wishing to create work that is weighted yet free. Her paintings are often imbued with a sense of movement. Forms appear to slip and slide over one another, an effect intensified by passages that suggest perforation or transparency. At times, the action implied is subtle or gradual. In Look Up, for instance, the left-hand portion gently expands, compressing its near-twin on the right. Some works are more dynamic, even tending in the direction of op art. Slivers of yellow and green in Piano seem to explode and rotate like spokes. Faulty Zip is marked by thrusting and spreading forms, akin to beams of light split by a prism. There is a cinematic quality to several of the paintings, the elements evoking transitions between scenes or experimental animations by the likes of Oskar Fischinger.

A heavy kite whistles in the wind.

The emphasis on flat geometric shapes in Heavy Kite inevitably call to mind mid-century hard-edge painting. There are also connections with earlier aesthetic movements—such as constructivism, futurism, and suprematism—in terms of both paint-handling and style. A number of works possess a distinct musicality, particularly Glass House and Score, which include elements suggestive of portions of instruments or musical notes. McMahon points to a parallel with posters used to advertise performances of jazz music. In the past, she has actively embraced the form of the poster, creating works featuring blocks that might be given over to text. With the exception of Slots, the works in Heavy Kite include no such space. The pictures are quite consumed by the bold abstract forms; words would struggle to be noticed.

A heavy kite can lift you up.

Although no text appears in Heavy Kite, paintings like Neck Dip and Score include forms reminiscent of fragments or stylised versions of letters. There is a sense that McMahon’s works are tied to some sort of sign system, pictorial if not verbal. Faulty Zip and Stop Over share points of similarity with flags or elements of the same. Ultimately, however, no message is retrievable. McMahon’s images are not in reality linguistic. Nor are they underpinned by a discoverable logic. No neat set of rules explains their colours, their forms, or the ways these come together. And yet, because the family resemblance between paintings is so strong, it is difficult to shake the sense that a unifying explanation could be found, if only one could spend enough time puzzling. The works captivate, and the longer one looks, the more complex they become. The kite pulls harder on the tether, testing one’s ability to stay planted to the ground.

Marlee McMahon, Piano, 2021, oil on canvas, 75.6 x 66 cm. Photo: Sam Hartnett

Marlee McMahon, Slots, 2021, oil on canvas, 75.6 x 66 cm. Photo: Sam Hartnett

Marlee McMahon, Score, 2021, oil on canvas, 76.5 x 66 cm. Photo: Sam Hartnett

Marlee McMahon, Paper Slide (detail), 2021, oil on canvas, 72.5 x 64 cm. Photo: Sam Hartnett

Marlee McMahon, Stop Over, 2021, oil on canvas, 75.6 x 66 cm. Photo: Sam Hartnett

Marlee McMahon, Look Up, 2021, oil on canvas, 66 x 76.5 cm. Photo: Sam Hartnett

Marlee McMahon, Faulty Zip (detail), 2021, oil on canvas, 75.6 x 66 cm. Photo: Sam Hartnett

Marlee McMahon, Faulty Zip, 2021, oil on canvas, 75.6 x 66 cm. Photo: Sam Hartnett

Marlee McMahon, Glass House, 2021, oil on canvas, 75.6 x 66 cm. Photo: Sam Hartnett

Marlee McMahon, Heavy Kite. Installation view, Visions, August 2021. Photo: Sam Hartnett

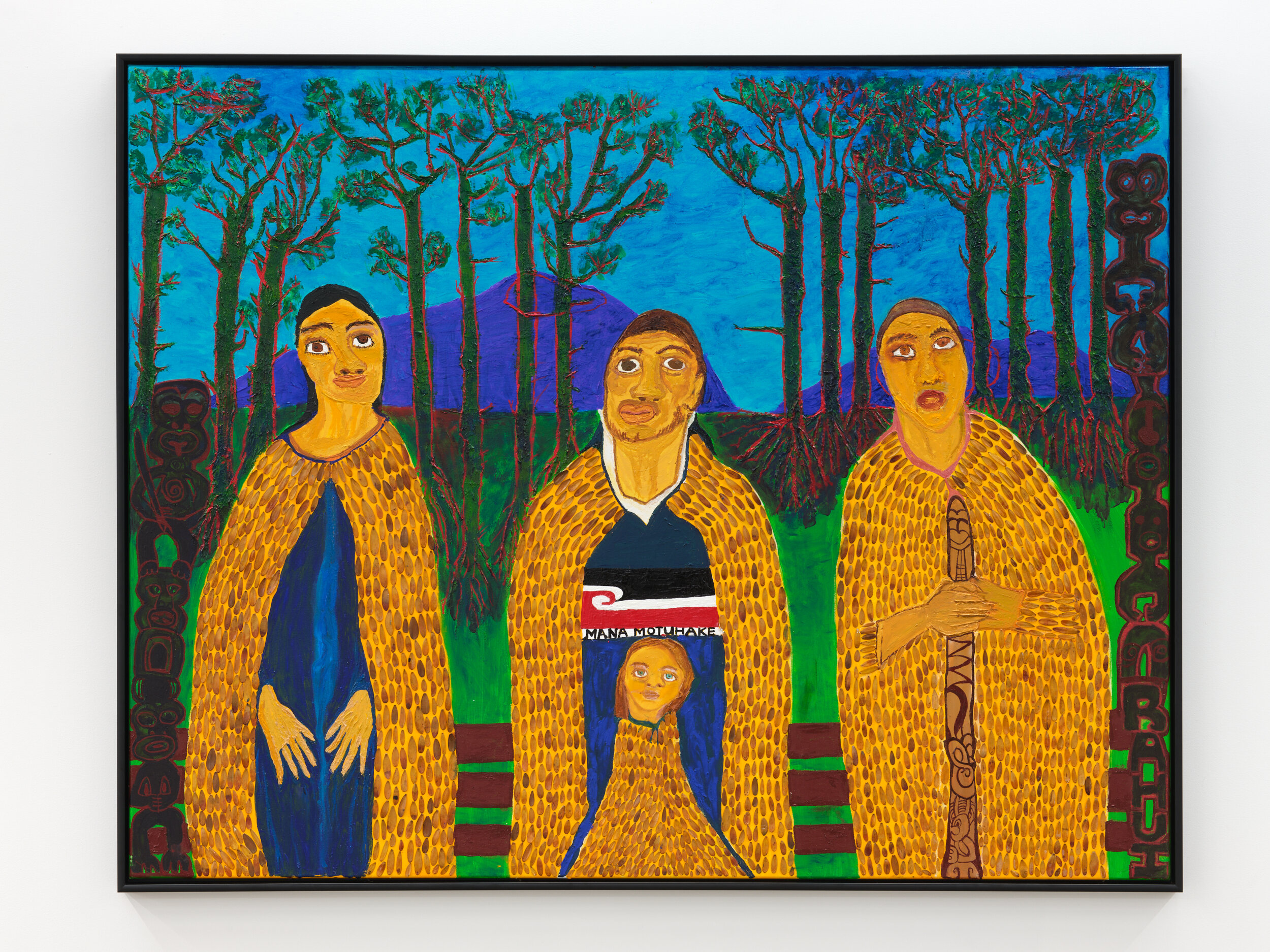

An essay by Sholto Buck on Nick Mullaly on the occasion of the artist’s exhibition at KAUKAU.