A Field of Joy: Energy, Hyperobjects and Artefacts

Sarah Smuts-Kennedy speaks to gallerist Dan du Bern on the occasion of her new exhibition Joy Field at Sumer, Tauranga—discussing her approach as an artist, what inspires her, and how she believes art can best function in the world at this specific point in time.

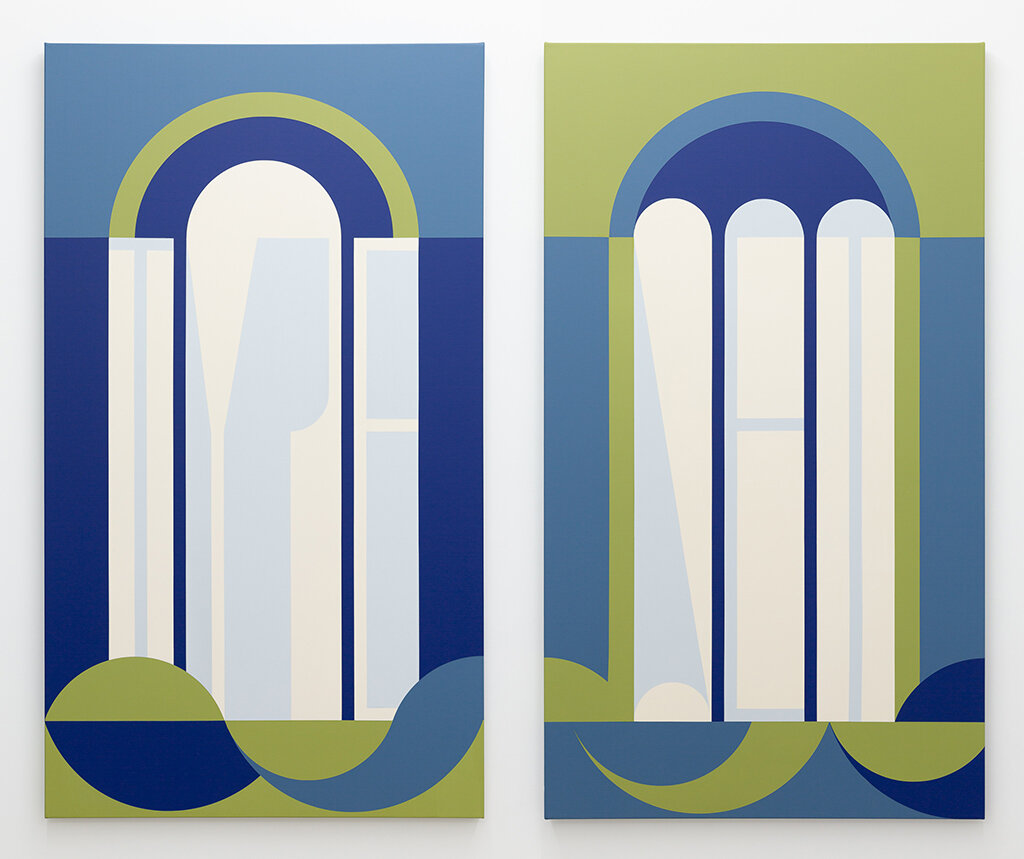

Sarah Smuts-Kennedy, Joy Field – June 23rd, Sun Studio, 2021, soft pastel on smooth cotton rag 640 gsm, brass, 52.4 x 106.7 x 2.5 cm each panel; 152.4 x 340.4 x 2.5 cm overall. Courtesy of the artist and Sumer

“Joy Field...refers to my interest in Timothy Morton’s concept of hyperobjects: objects that are so massively distributed in time and space as to transcend spatiotemporal specificity. He uses this idea to explore concepts such as global warming, however I co-opt this term to describe my desire to create artefacts that might populate the atmosphere to create an alternative hyperobject of balance and harmony—a joy field. The atmosphere is the largest thing we live within, and it is full of information. Immaterial information in the form of thought forms and frequencies from radio, satellites, to Wi-Fi and material information in the form of chemistry and biology. Rain and snow, by the way, is triggered by a microbial process. These things impact on the way an atmosphere feels to all living beings.”

— Sarah Smuts-Kennedy

Dan du Bern: Kia ora Sarah, can I firstly say that we’re so excited to finally be able to show your new exhibition Joy Field here at Sumer. It’s been a little while since we first visited you at Mahurangi, and discussed the possibility of showing the work here. I understand it’s been a full year for you—what with the birth of your grandson, your social initiative For The Love of Bees, and of course, the garden. It must feel good to be able to shift attention back to your studio practice again.

Sarah Smuts-Kennedy, Joy Field – June 23rd, Sun Studio, 2021, soft pastel on smooth cotton rag 640 gsm, brass, 152.4 x 106.7 x 2.5 cm each panel; 152.4 x 340.4 x 2.5 cm overall. Courtesy of the artist and Sumer

Sarah Smuts-Kennedy: Yes it really does. Since completing my studio in May of last year, I have been able to bring my attention back to parts of my practice that are enabled by having an intentional and dedicated space. As a result I have found myself diving very deeply into the process of mark-making; exploring the power of line, pattern, colour, rhythm and what occurs between these various parts as they emerge into dynamic relationships through the systems I use.

Perhaps I should start by asking how you would describe the works that visitors will see in Joy Field—what are these works to you?

The works hover between painting and drawing. They are dry media works on paper, held by brass bars that allow them to float off the wall or in space. I like the tension and awareness this suspension offers, pointing to the fundamental relationship we experience on earth between the forces of gravity and levity. I think of these artifacts as constructed fields of energy. Dynamic subtle circuits that are in perpetual and subtle motion.

I relate to the expression of materials through their material and immaterial qualities. I love the quality of the paper I use. It is a beautiful open organic substrate that draws towards itself and absorbs energy. Whereas the pigment pastels are a combination of different colours that are an expression of diverse chemical compounds that have come from across the planet, which behave in wildly unique ways.

In the past I have worked with lines that were more readily accepted as conduits for energy, such as copper wire that had been electroplated in silver, gold and nickel. These wire lines were inserted into plaster board, sometimes with crushed crystals or nuggets of brass, copper or silver. It was perhaps slightly more plausible to accept these were functioning as subtle circuits where the form, relationships and densities of these lines were harnessing subtle energy from the wider field, directing it, and giving it a new expression within a frame.

I came to think that the newer drawings were doing a similar thing. Each mark being a manifestation of energy that is harnessed by me, and its own complex chemistry and geological history. I relate to each mark as having its own material and immaterial expression. The drawing/painting framework allows me to compose a dynamic living relationship between these forces and expressions.

Through the process of materialising these marks, thresholds are crossed, where a thing becomes more than the sum of its parts. It is not something I can manage though mind. It is something that occurs through surrendering to the process. By focusing on being, rather than doing.

Ever since I encountered certain paintings that left an enduring and beautiful impact on me, I have longed to mark-make in a way that might emerge a multi-dimensional force from a two-dimensional plane. Where this thing, that is more than the sum of its parts, has transcended time and space; moved from the plane where it is held in perpetuity, and into the field of which my body is a part. These works affected me in tangible and non-language ways, which were experienced in a more than bodily form. They made my heart rate change, my biochemistry altered. And I can still evoke these effects by simply recalling these paintings in my mind.

What is the power of a drawing/painting? Of lines, patterns, colours, and rhythms? It is mysterious to me. It is a language I want to know. But my deeper question is, is this a language that can affect the field itself in the same way a vibrant living system such as my syntropic garden at Maunga Kereru does?

Sarah Smuts-Kennedy, Joy Field – Breath Together Now – Karmic Pattern – 15th March, Sun Studio, 2021, soft pastel on smooth cotton rag 640 gsm, brass, 152.4 x 106.7 x 2.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Sumer

Sarah Smuts-Kennedy, Joy Field – Journey home through the wilderness, Karmic Pattern – April 2nd Sun Studio, 2021, soft pastel on smooth cotton rag 640 gsm, brass, 152.4 x 106.7 x 2.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Sumer

We’ve spoken of the holistic view you take—on how your art practice fits into a larger scheme of things. That you do not differentiate between those things you make or do within your studio practice and those other creative enterprises within your life, be they social projects, your permaculture garden, or something else.

Many years ago I assisted Tina Barton when she began work on Billy Apple’s biography. I was required to go into the artist’s storage unit and help make sense of his archive. It was a huge undertaking. The space was considerable, and there were dozens of filing cabinets and many filing boxes within. All were full of all sorts of ephemera, as well as his collection of racing cars and motorbikes, and their various requisite spare parts. There was just so much stuff, some of which seemed only tenuously relevant to the things he had exhibited. Yet to both Billy and Tina they were all crucial parts of a larger whole; for Billy held the view that everything he did was art.

I don’t think that you consider your work in quite the same way that Billy did. Billy was a proponent of the Pop and Conceptual Art movements, and thus his attitude was one that revolved around the commodity, use-value and status of the artwork; or rather, as he put it, “the given as an art-political statement.”

Irrespective of differences, I do find it very interesting when artists, such as yourself, or Billy, actively seek to call into question the commonly held view that the two are clearly delineated—what should be considered art, and what is life. For me, not everything in life should be considered art, but anything in life has the potential to be art. And by this I am not wishing to say the term ‘art’ should be used as some qualitative descriptor as it so often regrettably is: designating something as exceptional, in terms of its beauty, elegance or sophistication. No, my meaning is rather that a thing may be considered art should an artist deem it so. What is salient here is the action, which must be invoked.

I was wondering if you could speak to this? And perhaps you would prefer to speak instead to some of the philosophical or theoretical principles that inform your practice—how you situate what you make or do?

Over a decade ago Judy Miller suggested to me that my gardening and the studio practices might not be two distinct projects but instead one singular enquiry. As I reflected on this I began to see how the questions and insights in one part of my research were present in all others including the project called my life. The tendency to perceive things as separate and to create areas of specialist knowledge is a critical driver of the systemic problems we face as a culture right now.

I have been trying to unpack this tendency towards a siloing of ideas and things, for it stands in contradiction with how I perceive holistic dynamic natural systems. The tendency towards specialisation, separation of knowledge and practices is inherently disabling. It clouds our capacity to perceive ourselves and the things we share space with, as a whole system. Viewing the activities I engage in as one project has been an empowering way to re-centre myself in life where I am able to come to know my part within a larger functioning system.

The title of the body of work I have been emerging since 2020 is called Joy Field. It refers to my interest in Timothy Morton’s concept of hyperobjects: objects that are so massively distributed in time and space as to transcend spatiotemporal specificity. He uses this idea to explore concepts such as global warming, however I co-opt this term to describe my desire to create artefacts that might populate the atmosphere to create an alternative hyperobject of balance and harmony—a joy field. The atmosphere is the largest thing we live within, and it is full of information. Immaterial information in the form of thought forms and frequencies from radio, satellites, to Wi-Fi and material information in the form of chemistry and biology. Rain and snow, by the way, is triggered by a microbial process. These things impact on the way an atmosphere feels to all living beings. For example it is easy to feel the vibe of a room full of people who hold hostility towards you, or conversely, one occupied by people that hold a space of respect and love for you. You can train yourself to feel, sense or anticipate the quality of their force field before you even enter the room.

People often express the desire to sleep when they arrive at a beach, or within nature, after having spent time in an urban environment full of pollutants and density of Wi-Fi and other radio waves. Our bodies, hearts and minds are reading and responding to the vibrations of the spaces we are in all the time. Simultaneously we are collectively putting vibrations into our common space through our thought forms and feelings—the objects we make or the processes we engage through the activities we are involved in. We are both receivers and broadcasters of information, being sculpted in our collective atmosphere 24/7 in multi-dimensional forms across time and space. My practice is a system for being conscious of how and what I contribute to this time and space. The project I am giving attention to at the moment is to seed and manifest a field of joy—a space that supports and nurtures life.

You used the word ‘emerging’ to describe your works’ creation in the studio; the more commonly used adjective is ‘making.’ Would you care to explain the difference and why you elect to use the former?

I prefer ‘emerging’ because the process suggests that the work already exists. What I do is allow it to find form in this dimension in this space/time. Think of it like a seed. The seed already has all the information within it, but it requires certain conditions for it to be able to express itself. External conditions and the information held within the seed coalesce, allowing it to become a plant—a plant that can go through many phases, that may produce leaves, flowers, and, one hopes, further seeds. Together they determine the quality and potential of the expression of the plant in this space/time, its contribution to the place it grows and the quality of its subsequent seed, which will find form in another space/time. The seed's expression is most often observed by us as a material thing, but some believe that there is an immaterial form also, that we can train ourselves to sense if we slow down and listen from another place within us. When we access this, another way of knowing emerges out of the fog. I feel it acutely under the canopy of an ancient tree, or now in my own garden. I see my grandchild respond to it as we walk around the property. In certain places where I have given it attention and it has emerged from behind the veil, he lights up and begins to squeal with delight. This potential is always there, but can only come into our attention when we actively choose to merge with it.

I once read British musician and composer Brain Eno refer to his process of composing music as him giving form to the music that already exists, which he could hear through his inner ear. This is also how I feel when I intentionally, and with precise attention, bring works into the world. It is why I think of my works as collaborations. I am doing them beyond our material understanding of self, or of process. The work is about creating the outer and inner conditions to coalesce so that form might emerge. It is important to me to expand my awareness of this process as it helps me to access the place within me that is able to bring the thing into being that is useful for our time. I don’t do this alone, I do this with and as part of the All.

Sarah Smuts-Kennedy, Joy Field. Installation view, Sumer, Tauranga, October 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Sumer

Within our materialistic society, as informed by capitalism, there is often the assumption that art primarily resides within the confines of a financially-based system, as a commodity. An artwork being just another object for consumption. A thing one can single out—to have, acquire, make their own. We don’t always think of art in the manner I feel it is most often intended by artists with integrity: as a philosophical proposition, or perhaps as in your case, a divining rod to a spiritual dimension. That is, unless we allow ourselves to actually engage with a specific work, the literal thing; and have the ability to quiet our prejudicial mind.

A while back I listened to an interview with British-American gallerist Maureen Paley, she spoke of art as being magical. I love this idea—that an artwork is not just another thing, but rather is something which is manifestly strange, mysterious, or mystical. And with this comes the understanding of art too as the domain of deep-thinkers, dreamers, and strident non-conformists.

In our past conversations you had also spoken about how our understanding of art must go beyond the belief that it exists solely within the confines of capitalism. I recently shared with you a quote by the late David Graeber; one that Adam Curtis had used to bookend his new documentary series, Can’t Get You of My Head (2021). We both agreed that it was right on the mark:

“The ultimate, hidden truth of the world is that it is something that we make, and could just as easily make differently.”

My interest remains centred around the creative act itself. The powerful choice humans have to choose to use their energy to create their experience, rather than to react to their experience. I have been engaged in a research project for decades that has been concerned with exploring the mechanism of creation as a strategy for restoring balance to living systems of which I am a part. How we perceive the world is largely determined by the stories we give attention to. Our seeing and listening is a determining factor in what we experience as real. And by this I mean the act of seeing and listening in an expanded sense. By shifting the 'c' within 'reaction’ to the front, you make ‘creation’—this is a symbolically important shift in how we can begin to experience the world we inhabit. Being able to create rather than react is aided by our capacity to imagine an alternative perspective before experiencing it. The imagination then becomes our critical tool in the possibility of transformation. The imagination is what gives us access to experiencing life not just from our heads but also from our hearts. It gives us agency to perceive beyond the material world to experience the material world in relationship to and within the immaterial qualities that give rise to concepts such as wonder, joy, bliss, love, harmony, trust and beauty. And when these qualities are abundant then life occurs as generous and fear finds it hard to get attention.

Capitalism works against these fundamentally abundant energies, slowly creating space for the opposite reflection to emerge, which is found in the thought forms of scarcity and fear. Most of the things emerging at the moment in the world are driven by these negative thought forms. I am not inspired by what these forms give rise to. So I spend a lot of time working with and within nature where I find easy access again to the syntropic qualities which give rise to the forms that do inspire me to live and call me into being.

The choice to create is my political act. The blessing is that it is also a spiritual act. It has given rise to my own spiritual nature—giving me access back into the wider field from which I came and will once again return. Being present to this while I am still in a physical form gives me access to the joy of being alive, to the gift of life itself. The drawings ground this learning, and doing them creates muscle memory of working with and within the field; wherein I get to experience myself as part of an infinite system whose natural state of being is to give rise to life.

Working within the natural system of chaos and order, I use the modality of contemporary art to learn how to trust myself, and trust living. By creating a system for surrendering to a process where I become a conduit for emerging things that have a life force that rises naturally; when chaos and order are given space to exist in balance. We all have access to emerging this force of life. It is our natural state of being to give rise to it. Our access to it is gifted to us via our imaginations, connected to our hearts, employing the discipline of using stories that evoke faith in our ability to emerge the goodness of things.

In past conversations you have used the word ‘service’ in reference to your practice. You spoke of the artist’s work as an offering, and this being driven by generosity, rather than something which is more self-serving, ego-driven or solipsistic.

I have been applying this act of service as an underlying principle within my practice since completing my MFA in 2012. In 2016, I used my residency at McCahon House as an opportunity to explore the potential of this approach over an extended period. Here, I focused on being in service to Kauri trees suffering from dieback, in relationship to the energetic legacy of Colin McCahon’s work The Wake (1958). Three times a day I would perform a Sanskrit fire procedure that I was told was beneficial to trees. After two weeks I had enough ash to paint one tree with an ash, clay and ghee poultice. Over three months I painted a total of seven trees. I gave my attention to being the best tool I could be to these trees; including fasting, changing what I ate, being in silence, limiting my computer time to a bare minimum. I gave attention to listening inwards towards the field and outwards into the natural world and waited to see what emerged. Eventually this gave rise to new bodies of work including the emergence of a drawing practice with the series called The Sound of Drawing; of which, coincidentally, Laurence Simmons likened to McCahon’s Fog Drawings (1973), a body of work that I was not aware of.

By locating one’s practice in a place of service to other, it offers a focused purpose for making work. It allows one to think of their work functioning as would-be tools. And by its very nature, it sets up a flow of energy from self back into the whole. Service to other is inherently service to yourself also, yet with an awareness of yourself as part of the All. It enables you to slip into the expanded flow of things, where synchronicities occur. It helps you get out of the whitewater where you can feel like you are dysregulated, or out of sync with the world. Certainly, you can move mountains in this place by doing what it takes, but it will take energy from you and can leave you depleted, with a sense of being alone. In contrast, when you choose to move into the flow of things, you receive energy through being in action. This shifts the rationale and experience of emerging work in a radical way and gives you access to a sense of being deeply connected to all that is.

As I start a new body of work I ask the question: “what is the most useful thing to do next?” Sometimes I use a pendulum to assist me in the decision making as it helps me access answers from the expanded pool of knowledge. By surrendering to this process I get to observe the outcomes as they come into view. I get the benefit of learning how to live by emerging them. But they are made for others. They are made as a contribution to the field of energy we are all immersed in. They are tools made with the intention of being part of regenerating balance.

Sarah Smuts-Kennedy, Joy Field – Good Feelings Yellow #2 – January 25th, Sun Studio, 2021, soft pastel on smooth cotton rag 640 gsm, brass, 152.4 x 106.7 x 2.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Sumer

Sarah Smuts-Kennedy, Joy Field, Sumer, 2 October – 6 November 2021

Related: Joy Field exhibition listing on The Art Paper

Gallerist Dan du Bern of Sumer on Hikalu Clarke’s current exhibition at the gallery.