The photo, a girl

Bridget Riggir-Cuddy on Ann Shelton’s recent presentation REDUX at Envy6011—originally commissioned by Envy6011 on the occasion of the exhibition.

Ann Shelton, Petrol Station, K Road, 1995–2003, 33.5 x 28.4 x 45 cm, framed, edition of 6 + 2AP. Courtesy of the artist and Envy6011

At fourteen I became fond of the ‘Nirvana section’ in our family library. A teen at the time of Cobain’s death, my eldest sister’s collection of the band’s publications and ephemera remained interspersed in the shelves of photo albums, Plunket books, and high school art projects. Mostly photo books, reading wasn’t required to gather what these publications lamented. Facsimile pages of Cobain’s personal journal leant understanding to the shared style of published fan letters. All perforated, my favourite was both book and bedroom poster collection. Belonging was a tear-away. I had accessed something authentic and feeling, becoming their adherent—looking like them, looking at them.

Ann Shelton’s 1997 photobook Redeye operated similarly in the Elam Library. A semblance of artistic being more attainable than romantic, it was easy to fashion ourselves in its pages. In its likeness to the magazines and music videos we were so versed in sourcing, and to our lives as they played out at art school and on K’ Road in our early 20s; the book was assurance. With the early lives of authority figures looking a lot like our own—outfits, openings, parties—all became a vital part of what would be our own myth.

*

A set of ethical tensions has persisted alongside the photographic image since its advent. Evolving with technology, media, and the social-political current, these problems remain stable at their core. Preeminent to this is the photograph’s ability to capture ‘the real.’ Photographic spectatorship, ever willing to overlook the context of the image’s production and platform, regularly obscures photography’s ability to in fact produce ‘the real.’

A creation story of those in galleries, books, and lecture theatres, we verified Redeye and made it our own. With the look and behaviour of Auckland artists, in 2014 we recorded mostly through Instagram. Documenting our early artistic lives in the automatic though somewhat temporary archive of social media, our images and relation to them would never be as Shelton’s.

The dominant subjective qualities of the photograph and its companion mediums, increasingly commonplace, were brought into heavy questioning by the feminisms of the 1970s. The effort of analysing and disrupting the ‘male gaze’ as a pervasive social structure was also met with the encoding of a ‘female gaze.’ So Shelton put herself behind and in front of the camera. Subjects not of a white-cis- hetero-male desire or experience were documented for the record, while the formal qualities of a distinctly female visual and narrative storytelling were devised to counter its usual role as spectacle to male protagonists and audiences.

There were also those who clowned, costumed, and camped the male gaze and their own bodies as its object; reproducing it through satire to weaken the default nature of its codes and their use in women’s advertising. Then, a kind of ‘gaze positivity,’ where male desirability was reclaimed as something acceptable to one's own image and its circulation. These strategic frames for the photographic image contended by ’70s feminisms and the history of desirability as a women’s marketing tool unfold much differently on social media today.

The nine photographs selected from Shelton’s mid 1990s – early 2000s portfolio for REDUX throw into relief today’s culture of image making and viewing. With the artist herself the subject of each, these photographs take on familiar narrative and purpose. These are documents of the artist’s look—her outfit, makeup, attitude—before, during, after, a night out. Imposing conventions and behaviours from our photographic current onto the visual field, we make these images selfies.

Popularised in the 2000s, the selfie allowed media personalities to cut out the middleman of the paparazzi, and provide fans with instant self-authored images via social media. Designed to ‘serve face’ the selfie is characteristically unconcerned with image quality, composition, or background noise. Made a convention through the proliferation of new media technologies and their cultural byproducts (such as Instagram and the Influencer), the selfie has overcome the categorical method of its name. Technically professional photos or those taken by others, are now also selfies; a sensibility that grows as everyday photo-taking aims more and more for the highly shareable self-image.

Only one of these photographs appears as if taken by the artist herself, yet we know these are self-portraits. They are her setup, concept, practice. The scene of each emulates qualities of a studio environment. Standing against flat-coloured backgrounds sourced through happenstance, the subject is lit by a halo of artificial light from the camera’s red-eye-giving flash—albeit for the ready-made halo found in the backlit Mobil Gas logo. The artist has positioned herself, handing to friends instruction and her Olympus Mju snapshot camera. Shelton replicated her photographic style and method through others photographing herself.

Treating herself to these makeshift ‘shoots’ the artist went about recording her ordinary as if it were anything but, almost as we do today. Misplacing the codes of fashion and music photography to her everyday, the artist burlesqued the frames of fame and the photograph as its producer. As Giovanni Intra put it: Of course it all amounts to the same thing: that glamour is a regime perpetrated by photography.(1) Shelton's turn of the century self-portraits purposefully and playfully replicated the authority of the photographic image.

In her ongoing enquiry into the photographic image as a device of self-agency and authorship, Shelton practices photographing a self in others, scenes, and objects. Leading us purposefully to the more limited idea of the self as contained in the body and the photograph of it, the selection of self-portraits for REDUX frames the artist's fundamental questions of the photograph to the regime of the selfie.

In today’s context, though the authority of image-making has transferred from mass media to the self- publishing social media user, greater power dynamics remain reproduced in this aestheticization of everyday life. Riffing on Tiqqun’s Theory of The Young-Girl as ‘capitalism’s ultimate form of living merchandise,’(2) Hannah Black maps the happening of women’s online self-image-making online in Further Materials Toward a Theory of the Hot Babe:

Today the “authentic” self of ideology requires a surplus made up of selves that are not perceived as “authentic”—among them is the Hot Babe.... Once, only the professional Hot Babe adorned all major media outlets; now social media makes of everyone a Hot Babe, should they be willing. What is private, secret, is not the detail of the life but the disappearance at its core.(3)

For REDUX Shelton maintains her previous title of Foucoult’s 1982 seminal Technologies of the Self to contextualize the photograph as a tool in the social construct of the individual. In the regime of the selfie, how does the photograph, never so writhe with life, contribute to the individual as it is socially required? Exaggerated in presence, though reduced in substance entirely—as Black would have it.

As Shelton’s self-portraits malleate to our current context to become selfies, more than the fundamental trickiness of the photographic medium itself, I think of its trickiness to the ‘girl.’

*

Back in the Elam Library Redeye held the myth and collected hopes for the life of the ‘artist girl.’ Whatever the alternative, grunge or art scene, we find our ourselves models in the record.

Sharing Shelton’s desire to live as an artist, we lived by replicating her images of it. The artist’s self- portrait can, after all, affirm her purpose, place, even make her real.

Ann Shelton, At home, K Road, 1995–2003, 33.5 x 28.4 x 45 cm, framed, edition of 6 + 2AP. Courtesy of the artist and Envy6011

Ann Shelton, Before the Hero party, K Road, 1995–2003, 33.5 x 28.4 x 45 cm, framed, edition of 6 + 2AP. Courtesy of the artist and Envy6011

Ann Shelton, London Nightclub, 1995–2003, 33.5 x 28.4 x 45 cm, framed, edition of 6 + 2AP. Courtesy of the artist and Envy6011

Ann Shelton, Verona, 1995–2003, 33.5 x 28.4 x 45 cm, framed, edition of 6 + 2AP. Courtesy of the artist and Envy6011

Ann Shelton, Monica magazine shoot, Teststrip, K Road, 1995–2003, 33.5 x 28.4 x 45 cm, framed, edition of 6 + 2AP. Courtesy of the artist and Envy6011

Ann Shelton, Verona restroom, 1995–2003, 33.5 x 28.4 x 45 cm, framed, edition of 6 + 2AP. Courtesy of the artist and Envy6011

Ann Shelton, At home, K Road, 1995–2003, 33.5 x 28.4 x 45 cm, framed, edition of 6 + 2AP. Courtesy of the artist and Envy6011

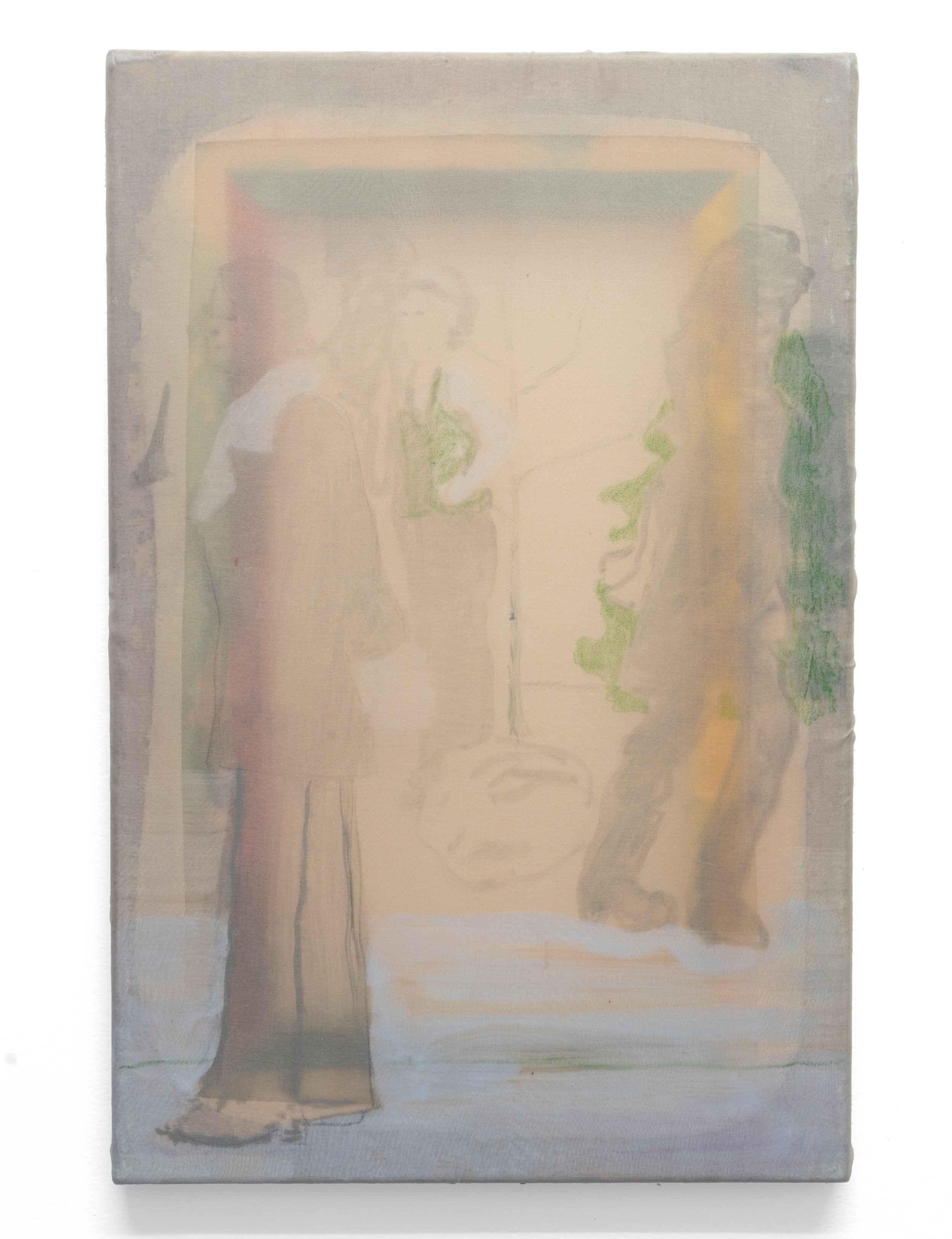

Installation view, Ann Shelton, REDUX, Envy6011, October 2021

Fergus Porteous on Rangi White’s Whakapapa Plasticus; Grace, 29 February – 30 March 2024.