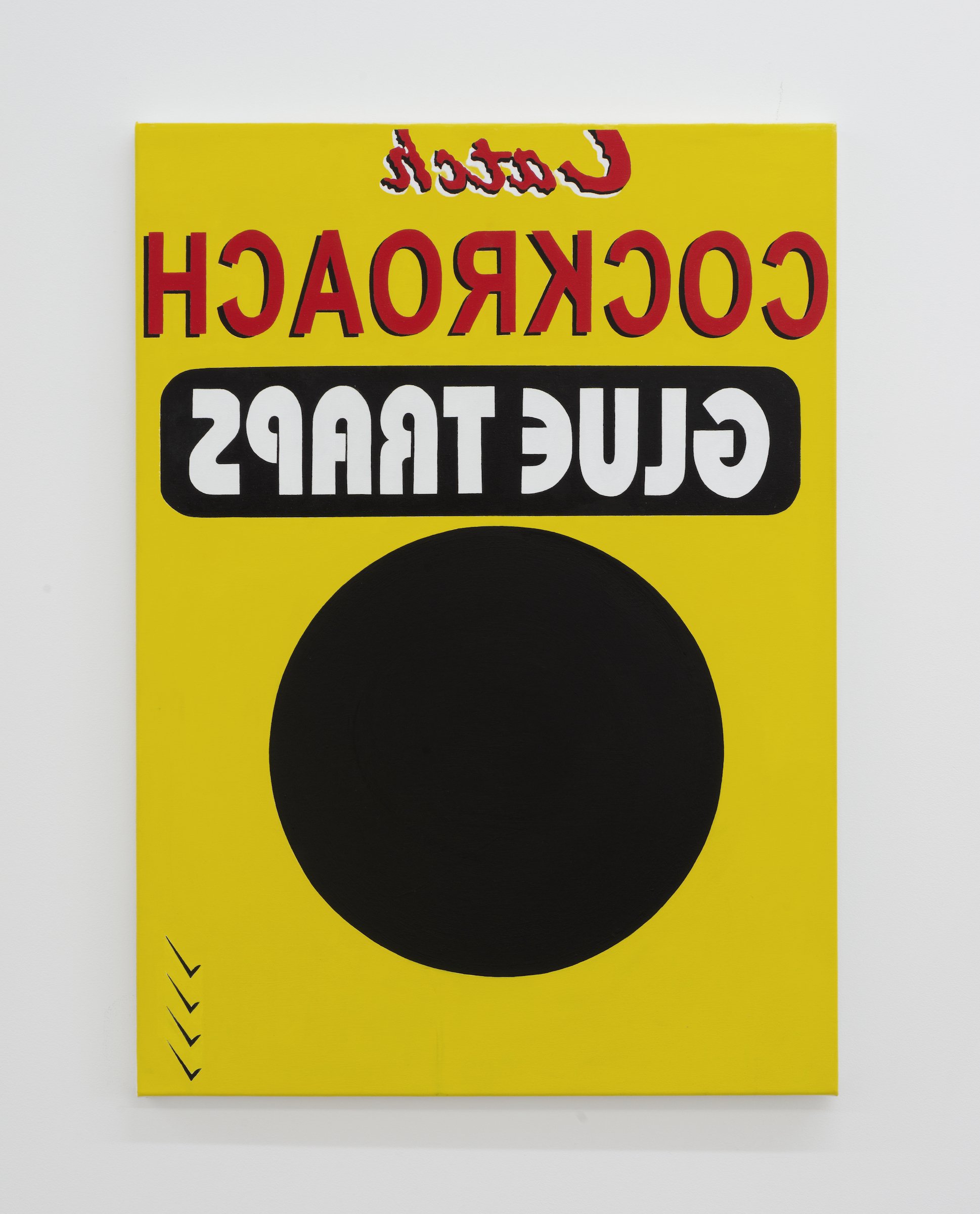

ARCHIVE: scratched flowers

Lucinda Bennett on Emma McIntyre’s The blue of it, commissioned by Hopkinson Mossman on the occasion of the exhibition (28–30 June 2019).

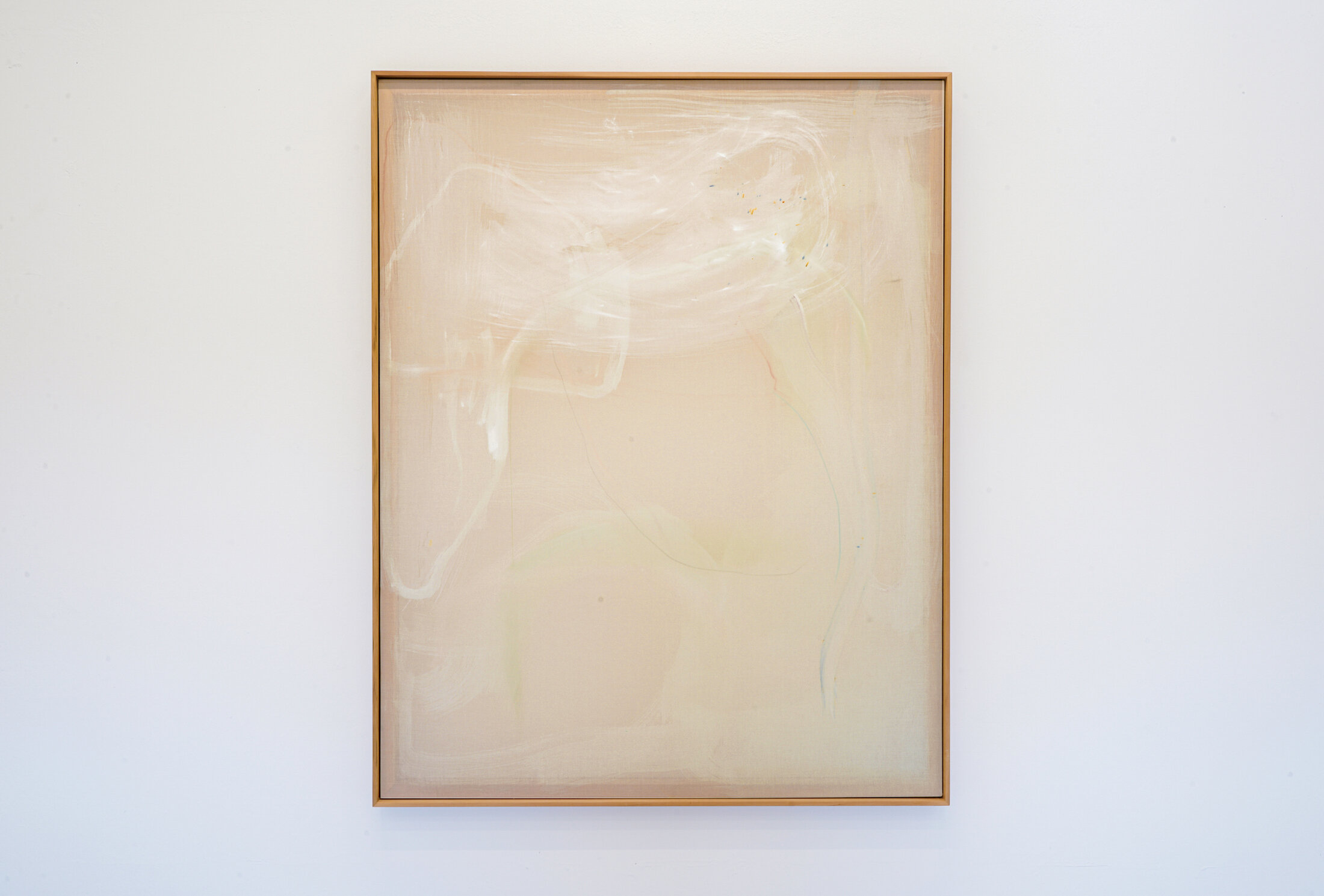

Emma McIntyre, S., 2019, oil and flashe on linen, 40 x 50 cm

1. Suppose I were to begin by saying that the paintings are too beautiful. A compliment wreathed in thorns. Beautiful is beautiful. Too beautiful is too much of a good thing. When something is too beautiful, we are suspicious.

2. If paintings were baths, these would be skin-warm and scented with lilac, filled with rose petals and cream. Only once you have stripped bare and lowered yourself into the water do you feel the silky layer of silt at the base of the tub. It’s only when the milky flower water begins to swirl that you notice the scum, a thin grey film of old soap and someone else’s oil congealing at the edges.

3. They are beautiful because they are made of vivid, petal colours blossoming over dark ground (flowers grow from dirt), a roseate glow.

4. In Patrick Süskind’s Perfume, the protagonist concocts a scent to disguise himself as human amongst humans. At the base of this perfume is dirt and excrement, an acrid awful musk without which Grenouille’s concoction would fool no one. The book ends when he walks into the fish market where he was born and douses himself in another perfume of his own creation. While wearing just a dab, Grenouille was pardoned from his own execution, offered adoption by the wealthy father of his murder victim. The whole town is incited to participate in a mass orgy around the base of the empty gallows. Now in the fish market, christened with the whole phial, people are overcome with desire. Carnal possession will no longer do and so the crowd tears him apart, consumes him.

5. To be in excess of beauty might be to transform into something else entirely. Emma McIntyre’s paintings seem caught mid-transformation – into what, I cannot say.

6. Emma’s is as much a process of taking away as laying down, washing as much as painting. Look closely and the canvas is like cracked agate, oil paint split by solvent to form something like a mineral seam. Sometimes she uses a wooden tool like a wand, with a pliable rubber tip, carving curves through clouds of paint. As if colour could be further revealed by scratching.

7. What these scratches do reveal is bodies, especially my body before them, and the artists body, and the space between us. The length of her arm, the dance of painting. Where my body fits into the grid, traces the curves, drifts forward and back.

8. Serum paintings caught and jarred in frilled frames.

9. In the real world, albeit the world of Sicily in the mid 17th century, a real woman named Giulia Tofana concocted a tincture she called Acqua Tofana and claimed was cosmetic. Somehow, the people most interested in her product were women in miserable arranged marriages, and somehow, the husbands of these women tended to die shortly after purchase. It’s estimated that over 600 men died from unwittingly ingesting Acqua Tofana. That something procured to make a woman look more lovely could kill the man who did not deserve her.

10. It is believed that Giulia Tofana was executed for her efforts, taking the recipe for her elixir to the grave – for while all historic accounts of Acqua Tofana stress its potency and undetectablity, the strength and certainty of her poison have proven impossible to replicate today.

11. When I visit Emma in her studio, I bring us both coffees with cream. I keep thinking of the line we drank coffee with so much cream we tasted only cream but I can’t remember where it is from. Later that night, I’m re-reading an essay I love, having recommended it and felt the urge to revisit it myself. And there amongst the pages is the line about coffee with so much cream, except it is a quote from a poem by the writer’s ex-boyfriend. When I type it into Google and the only result is the essay, I feel smug on behalf of the writer. His line leads back to her response, her defence of sweetener and cream: how can I express my faith that there is something profound in the single note of honey itself?

12. For all their beauty and brightness, these are serious paintings, earnest paintings. They wobble like a voice that has something to lose. A person can be sweet and still have something worthwhile to say.

13. An alternative title for this show was Bedroom Paintings. I gasped when Emma told me this, because that is a category of paintings I instinctively gravitate towards. A bedroom painting is a painting you can collapse into. It’s a special painting you choose to live with, one that will hold your attention even when beauty fades.

14. I suppose I am compelled by the way they blink out at me, coloured not by one pigment but by darkness glimpsed behind so many washes of gossamer colour, beyond a cellophane curtain, a thousand light years away. The stars we see shine from the past. The painting we see is an accumulation, a duration.

15. I don’t want to describe them as flat because they are so full – and yet. Perhaps the best way to describe them is as a night sky full of stars but no moon. With no one focal point, your eyes scan the heavens, rove from pattern to constellation. The canvas is boundless, woven with secrets.

16. “The notion that art is the mirror of nature is one that appeals only in periods of scepticism. Art does not imitate nature, it imitates a creation, sometimes to propose an alternative world, sometimes simply to amplify, to confirm, to make social the brief hope offered by nature.” (John Berger)

17. Maybe I’m just sick of pink and lavender and clouds and daisies being one-dimensional. It’s a relief to fall into something, to fall away from cynicism, towards poetry.

Emma McIntyre, F., 2019, oil, flashe, netting on linen, 30 x 25 cm

Installation view, Emma McIntyre The blue of it, Hopkinson Mossman, June 2019

Emma McIntyre, B., 2019, oil and flashe on linen, 40 x 50 cm

Emma McIntyre, N., 2019, oil and flashe on linen, 25 x 30 cm

Emma McIntyre, P., 2019, oil and flashe on linen, 60 x 45 cm

Emma McIntyre, I. (detail), 2019, oil and flashe on linen, 180 x 240 cm

Bridget Riggir-Cuddy on Rea Burton and Meg Porteous, Birds; Neon Parc City, Naarm, 21 October - 19 November 2022.