Murmuring Shadows

Hamish Coleman, Wax and Wane. Installation view, Season, Tāmaki Makaurau, May 2023

You could be seated in a cinema. Pictures unfold within borders of darkness. They glow in implausible Technicolor, establishing shots for a movie with no name. Perhaps you are contemplating a different kind of transparency: a handcoloured lantern slide projected within a dusty lecture theatre, a plastic slide held up against harsh daylight. Maybe you are leafing through a photograph album, its black paper pages forming a backdrop for a collection of family snaps. Or you could be looking out the window of a gloomy room, on to an Albertian world summoned into being by the hand of the artist.

Can you hear the whisper of the wind?

The work of Hamish Coleman might at first appear clear-cut. Although he has a keen interest in formal abstraction, which often manifests in his paintings as blocks and screens of colour, his mode is broadly representational. The core subjects of his works tend to be recognisable, taking in human figures, rural and urban landscapes, architectural elements, and utilitarian devices. These days, the pictures derive from videos Coleman himself creates. He makes the recordings with relative casualness. Angles and frames are not predetermined. Settings are not staged. The approach is intended to yield imagery that does not feel contrived or melodramatic. Stills are chosen for their visual appeal, then converted into drawings and paintings with meticulous care.

Wax and Wane, a collection of five paintings made this year, develops out of two bodies of footage. Bathed in Pink and the show’s title work, Wax and Wane, are from video of Coleman’s partner, the artist Emily Hartley-Skudder, shot in candlelight. The footage was made at their new home in Ōtepoti, to which they recently relocated from Te Whanganui-a-Tara, their base for the past decade. The other paintings in the show—As Days Get Dark, Shadows Lengthen, and Tag—are from recordings made during a visit to Coleman’s hometown, Hakatere Ashburton, in connection with On Returning (2021), his first solo exhibition at a public institution.

Coleman’s source material carries significance for him. He acknowledges that his work is, in part, an exploration of the intricacies of our memories and mental states, and particularly the ways in which these interact with our experiences of place. Occasionally, the titles of his paintings give subtle clues to personal associations. Tag, for instance, alludes to the game of the same name, which Coleman played as a child. However, his works are not baldly diaristic. They have no explicit agenda or narrative. Coleman is quite content to die a metaphorical death as their author. Indeed, he prefers his paintings to be framed in obscurity and inflected by mystery.

The paintings themselves frequently emphasise their openness, their status as departure points for flights of interpretive fancy. Bathed in Pink, for example, uses cropping to obfuscate the identity of the human subject. The image is distanced from portraiture and made more universal. At the same time, a sense of intimacy is retained, even intensified. As Days Get Dark—which focuses on a woman seen from behind—does something similar. The total absence of a face provokes our curiosity. We wonder where the figure’s gaze falls and what she is thinking about. The work also enacts a game of ‘follow the leader’, engaging us as would-be visitors to the painted world, rather than mere onlookers.

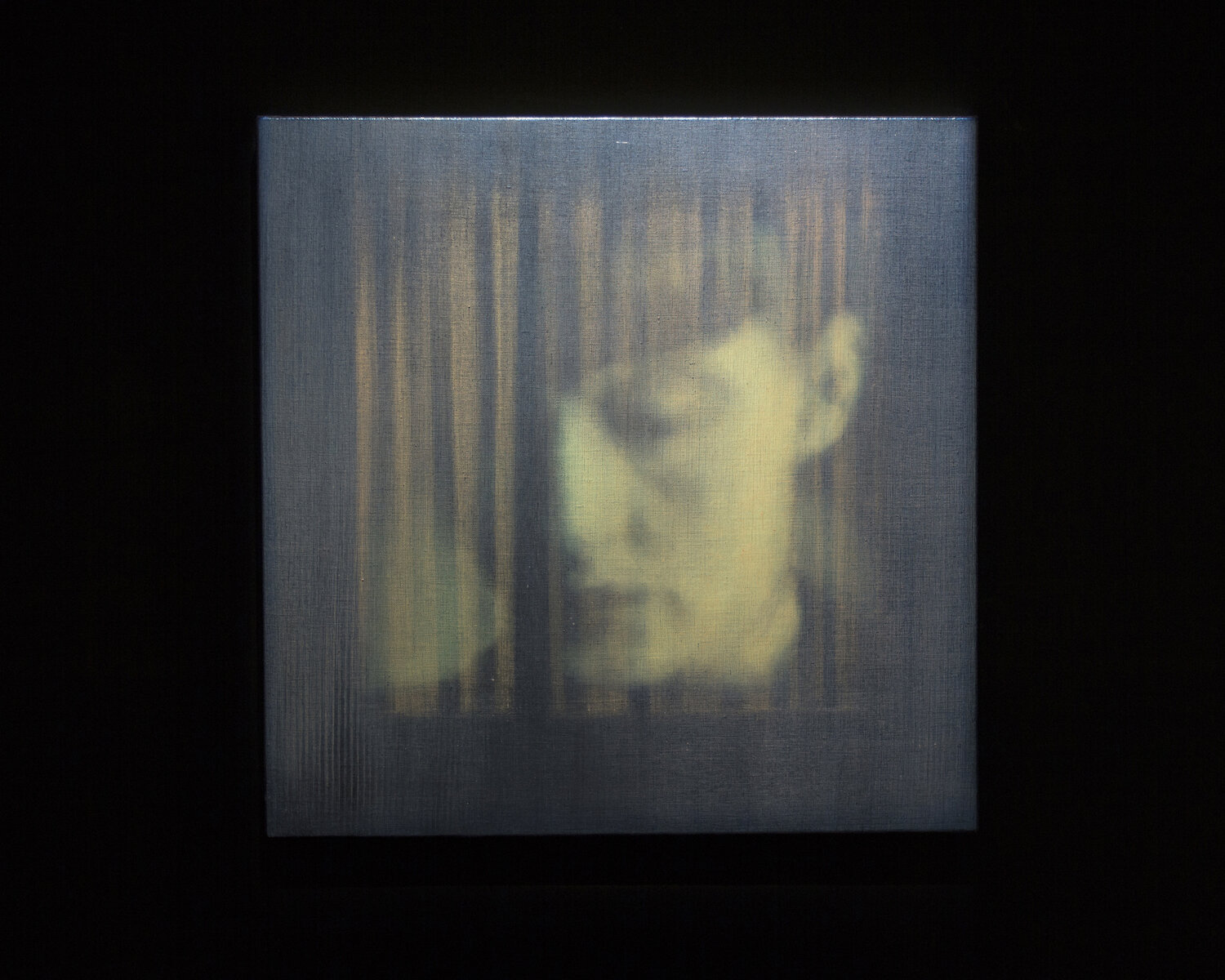

Hamish Coleman, Tag, 2023, oil on linen, 40 x 40 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Season

The locations of the paintings in Wax and Wane are purposely kept unclear. As Days Get Dark and Tag might strike a familiar chord for those who know Hakatere. However, the environments depicted are not exclusive to the area. Analogous scenes can be found all around New Zealand. In fact, the works are not obviously situated in this country at all, not least due to the presence of trees that appear to be introduced, as opposed to native. It is not difficult to imagine viewers from other parts of the world projecting their own places of origin on to the pictures. Furthermore, the vaguely European nature of the environments recalls the extent to which Aotearoa has been reshaped by colonial hands.

Shadows Lengthen is ambiguous in setting and subject. Centring on an avian entity, it evokes Gary Baigent’s well-known photograph Pigeon, Parnell, Auckland (1965)—showing a pigeon suspended above a busy railway yard—and the bird paintings of Don Binney. The work depicts not a real animal but an agricultural decoy, an artificial bird of prey patrolling the cropland to frighten away other birds. The decoy is outlined against a shimmering, peacock-blue sky. To the right is the faintly discernible form of an arm and cable from which it swings. Learning the true nature of the flying object only increases the intrigue. The painting remains beguiling as an image and takes on new significance as a reflection on land ownership and use.

As the exhibition title suggests, the works in Wax and Wane are united by an interest in light and shadow. Some feature cast shadows, others forms in silhouette. Coleman adopts techniques used by the ‘Old Masters’ to convey light effects, such as chiaroscuro and sfumato. His images generally feel realistic, yet physicality is often deduced by the viewer as much as it is delineated by the artist. For instance, we read massed foliage in the light dotting the central tree in Tag. Our perception of Coleman’s pictures is coloured in no small part by our familiarity with photographic imagery. Conversant with the language of still photography, we interpret the soft focus of Bathed in Pink as an artefact of low lighting and know the hazy treetops in As Days Get Dark to be wind-blown.

Coleman’s practice wears its affinity for lens-based art on its sleeve. Inevitably, any painter of the present day is working amid a vast ocean of photography. Photographic images, still and moving, are omnipresent, documenting and shaping our perceptions of ourselves, our family and friends, and an ever-expanding cast of individuals whom we know predominantly via camera work. Coleman offers a two-way response. In sympathy with artists like Gerhard Richter and John Ward Knox, he produces works that share properties with photographs and do things that photographs usually do not. He exploits our deep connection to lens-based images and our appetite for works of art that press beyond photographic space—and especially digital photographic space.

Hamish Coleman, Wax and Wane, 2023, oil on linen, 140 x 120 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Season

Those interested in the history of photography might detect in Coleman’s work allusions to earlier traditions. Atmospheric blur and shadow are hallmarks of pictorialism, a movement that rose to prominence in the early twentieth century. Popular among members of ‘camera clubs’, it sought to play up painterly effects in order to reposition photography as an artistic and expressive—as well as documentary and utilitarian—medium. The near-monochromatic nature of Bathed in Pink and Wax and Wane recalls earlier paintings by Coleman evoking black and white, or sepia, photographs. Here, however, the limited palette can largely be explained by the fact that the source footage was shot in candlelight, which supressed chromatic range.

The overall form of the same two works, a rectangle with its lower corners neatly removed, has diverse connotations. It suggests entities associated with photographic images—including shaped picture mats, mounting corners, and album pages sliced to enable the insertion of prints—and the ‘corner paintings’ of Colin McCahon and Milan Mrkusich. The canvases also call to mind abstractionists such as Gretchen Albrecht, Alberto García-Álvarez, Carmen Herrera, and Frank Stella. Like them, Coleman uses supports in non-standard shapes to emphasise the fundamental objecthood of his paintings. In numerous works, he pushes the boundaries of representation, creating solid borders around his central images, then quietly straying beyond them.

Coleman’s practice has long connected with Aotearoa art history. His use of soft shading evokes the work of Jude Rae, particularly her images of fabric from the 1990s. Many of his paintings echo conceptions of the ‘New Zealand gothic’, being marked by a faintly unsettling air—a curious combination of nostalgia and its opposite. Wax and Wane, with its fine paint layers and dark palette, speaks to gentler works by Tony Fomison. As Days Get Dark is in sympathy with photographs in the gothic tradition, such as Laurence Aberhart’s images of smalltown graveyards and monuments. It also recalls Rita Angus’s paintings of Bolton Street Cemetery from the late 1960s, and Robin White’s Concrete Angel works from the following decade.

Among the most striking aspects of Coleman’s works is his use of ‘interference pigments’, pigments that disrupt the waves of light that strike them. Made of titanium-coated mica particles, the pigments yield unusual and enchanting visual effects. Some change colour, depending on the angle at which they are viewed. Some shine like metals or sparkle like gemstones. Coleman typically sources the pigments from Australia and Japan. He is unusual in employing them in the production of oil paints; they are more often found in car paints, nail polishes, and other substances from outside the field of art-making. Mixing his own paints, Coleman is able to access a wider range of colours and effects than is available with over-the-counter products.

Each work in Wax and Wane begins with a dark ground, which goes on to form the frame around the central image. The approach is possible because interference pigments grow in intensity when they are applied over dark colours. In As Days Get Dark, the copper veil is noticeably stronger where it overlays the black cherry skin of the margin. Likewise, the crisp green rectangle in Wax and Wane is most legible at the top left, where it is offset over the border. Here, the interference layer disrupts our understanding of how the picture has been made, giving the impression that a printing process has been used. No such process is at play. As with all Coleman’s works, the reference image has been produced by camera then translated into paint strictly by hand.

The balancing of human and mechanical perspectives in Coleman’s practice yields works that are remarkably concise and remarkably convincing. No viewer will struggle to spot the ring on the hand in Wax and Wane, though it is described by little more than a highlight and answering shadow. A kindred economy can be found in Girl with a Pearl Earring (c.1665) by Johannes Vermeer, an artist who is understood to have made works under the influence of an optical device—namely, a version of the camera obscura. As Vermeer did, Coleman uses the camera to make light, rather than objects, his fundamental subject. He does not merely copy lens-based images but hones his vision in relation to them.

Hamish Coleman, Wax and Wane, 2023, oil on linen, 140 x 120 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Season

The verisimilitude of Coleman’s pictures makes them feel familiar, immediately. We sense that they are derived from a world we could wander through. We are equally convinced that their stories extend beyond their frames and frozen moments. Time only enhances the effect, for the longer we look at the works, the more complex they grow. Finer details, such as the lens-flare-like flash darting across the top left corner of Bathed in Pink, become more apparent. So do material properties and painterly gestures. Coleman’s borders reveal themselves to be brushy and sticky. Shadows fragment into strokes of dark purple, highlights into puddles of pearlescent cream. When the overall image inevitably re-emerges, it does so in a state of heightened tension.

Throughout, Coleman’s images remain suffused by a keen sense of poetry, a depth of feeling that overspills the bounds of formal sophistication or technical rigour. Images that might otherwise seem humdrum—a mechanical scarecrow, a tree in a field, an unidentified ear—become poignant and transcendent, expressions of both heartfelt connection and sober reflection. Coleman opens a space for contemplation, one that is restive and energised. As we move about his works, watching them flicker and shape-shift, we are made collaborators. Today, a hand reads as an emblem of benediction. Tomorrow, a shadow mocks the wing of an angel.

Can you hear the whisper of the wind?

There is no wind. Still, you hear it

Hamish Coleman, Shadows Lengthen, 2023, oil on linen, 40 x 40 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Season

Hamish Coleman, As Days Get Dark, 2023, oil on linen, 120 x 120 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Season

We visited the opening of Kith and Kin on Friday 2 August at Season, featuring brunelle dias, Tony Guo, Levi Kereama, Claudia Kogachi, and Jacqueline Fahey.