Kogachiworld

K. Emma Ng on Claudia Kogachi’s exhibition Heaven must be missing an angel at Jhana Millers—commissioned by Jhana Millers on the occasion of the exhibition.

Claudia Kogachi, Heaven must be missing an angel. Installation view, Jhana Millers, Wellington, April 2022

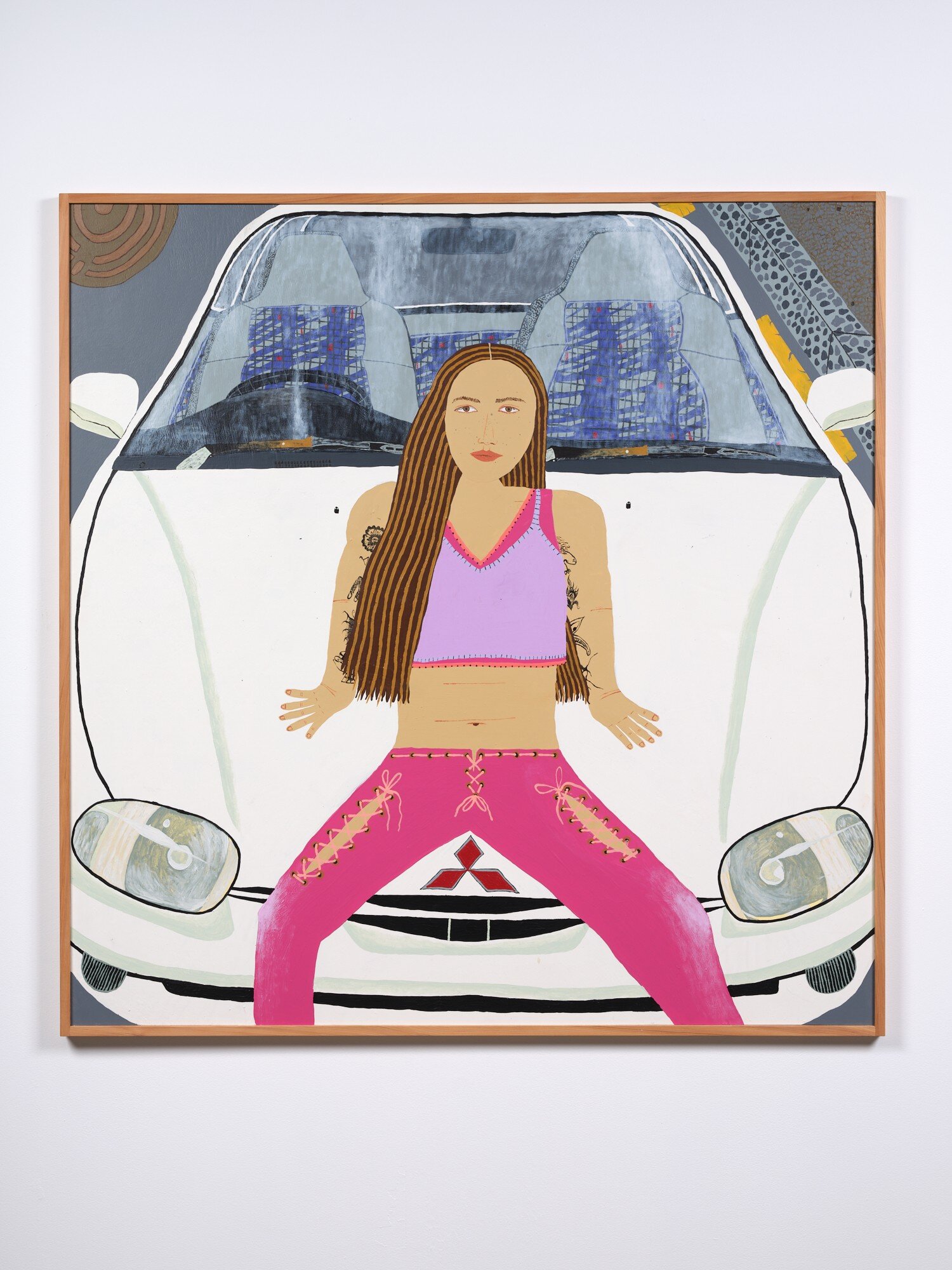

Claudia Kogachi, Kill Bill, 2022, acrylic on canvas, framed, 170 x 138 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Jhana Millers

Claudia Kogachi can’t resist inserting the people in her life into her paintings. This time, it’s her partner Josephine alongside her, in imagined moments from iconic movies. Together, they’re (two of) Charlie’s Angels; they’re Catwoman and Batwoman; they’re Uma Thurman and Lucy Liu in Kill Bill; they’re recreating the sexy pottery scene from Ghost; they’re together on a horse in Brokeback Mountain; and they’re Vin Diesel and Michelle Rodriguez in The Fast and the Furious.

The series is a continuation of Claudia’s movie fantasies, which began with Self Portrait as Suki, exhibited at Artspace Aotearoa last year. In that painting, Claudia reclines on the hood of a car in the manner of Devon Aoki in 2 Fast 2 Furious. Along with Lucy Liu, Aoki was part of a miniscule pantheon of cool Asian girls on-screen in the 2000s. But already, I’m underselling the fun of Claudia’s work. Aoki and Claudia might have Japanese-ness in common, but it’s not so much about “seeing yourself represented on screen,” and instead about believing that you could be anyone—even Vin Diesel. After all, Vin Diesel is already a cartoon, so why shouldn’t Claudia paint herself in his place, complete with muscle tank and chains?

Claudia’s paintings hum with energy, with snappy colours and instinctive, wavering lines. But their most overwhelming quality is their embrace of Surface. As objects, these paintings are large, flat, and hard-edged. Paint is mostly applied without shading or modelling. The light is high-key. In Kogachiworld, no one ever casts a shadow.

Surface has been accused of all sorts of things—at worst, seen as a distracting denial of depth or reality. In The Society of the Spectacle (1967), Guy Debord wrote of a “flattened universe” that “obliterates the boundaries between self and world” as well as the “boundaries between true and false”. Claudia’s paintings don’t make us forget these boundaries, but they do play with them. They unzip a space between these zones of “self and world” and “true and false.” Each painting is like a twilight zone that exists somewhere between fact and fiction, somewhere between the self and the world at large.

Kogachiworld is a space for play. Play is a process that allows people to test and develop their sense of self in relation to the world around them. In the expansive plane of each of Claudia’s paintings is a whole little world to play in, where everyone—regardless of their hair, skin colour, sexual orientation, weak or strong physique—gets to be a protagonist.

There is a boundless sense of possibility that comes from casting yourself in your own art—turning yourself and your figures into hypersubjects. They are always in motion, identities continually evolving, always a step ahead of any attempt to fix them to one particular idea.

With this series, it’s tempting to compare Claudia to other artists who like to dress up, like Yvonne Todd or Cindy Sherman. All three have created distinctive worlds to play in, populated by ever-shifting hypersubjects—and all three delight in a bit of ugliness. It feels wrong to say that there’s some ugliness in Claudia’s paintings, because ultimately they’re so appealing, but it’s true—Claudia doesn’t shy away from ugliness. Think of her series where everyone is bothered by flies, mosquitoes, and roaches; or those gassy green fumes in her artworks about IBS; or her celebration of flawed human ego in her paintings about mother-daughter tension.

Speaking of emotional ugliness, sometimes it feels like the painter is on a bit of a power trip. She gets to imagine how a situation might play out, manipulate each figure like a marionette, and set their features to her will. Having the last word is the artist’s privilege. Josephine must be relieved that in this series she gets to share in loving gazes and kick some butt alongside Claudia.

But in Kogachiworld nothing is ever dire. More often, the emotions that wiggle their way through Claudia’s paintings tend to be mildy annoying, a little offputting, or maybe the hehe kind of funny. Even the romantic moments in this series have a gentle sweetness, like a fingertip tracing a heart in steam on the bathroom mirror.

Claudia treats life and fiction as equally malleable, bending the narrative truth of both towards each other until they meet. Her artworks are imaginary negotiations of real relationships and real feelings. And it is because they dabble in minor feelings that these artworks are so relatable.

So, give in to their charms, and allow yourself to pass through the Kogachiworld horizon. In Kogachiworld it’s neither day nor night. In Kogachiworld there’s no such thing as two- or three- dimensional. In Kogachiworld everything is real and everything is made-up. In Kogachiworld you are ageless. You can be your own hero... or antihero. Kogachiworld is for trying on new identities, and slipping them off again. In Kogachiworld you can be anyone you want.

Claudia Kogachi, Mr. & Mrs. Smith, 2022, acrylic on canvas, framed, 122.5 x 92.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Jhana Millers

Claudia Kogachi, Ghost, 2022, acrylic on canvas, framed, 122.5 x 92.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Jhana Millers

Claudia Kogachi, The Fast and the Furious, 2022, acrylic on canvas, framed, 170 x 138cm. Courtesy of the artist and Jhana Millers

Claudia Kogachi, Blue Crush, 2021, acrylic on plywood, framed, 122.5 x 123 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Jhana Millers

Claudia Kogachi, Brokeback Mountain, 2022, acrylic on canvas, framed, 170 x 138 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Jhana Millers

Claudia Kogachi, Charlie’s Angels, 2022, acrylic on canvas, framed, 170 x 138cm. Courtesy of the artist and Jhana Millers

We visited the opening of Kith and Kin on Friday 2 August at Season, featuring brunelle dias, Tony Guo, Levi Kereama, Claudia Kogachi, and Jacqueline Fahey.