We chat to Claudia Kogachi

The artist discusses the evolution of her practice, rug-making, and painting the people closest to you — in the context of her exhibition It is what it is, through 10 April at Jhana Millers, Wellington.

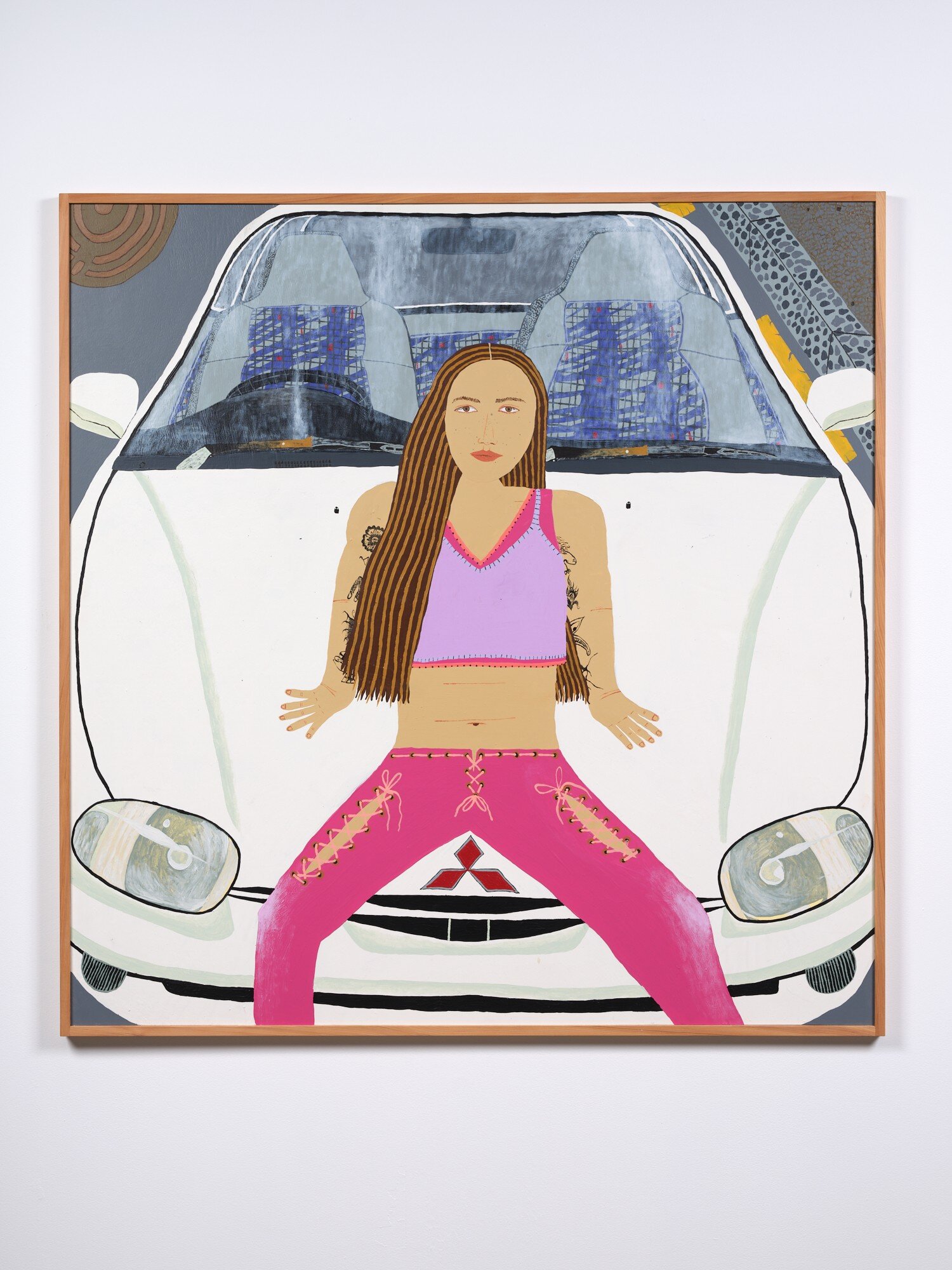

Claudia Kogachi, It is what it is. Installation view, Jhana Millers, Wellington, March 2021

Claudia Kogachi, The one with the cockroaches (diptych), 2021, acrylic on canvas, 65 x 65 cm each

Becky Hemus: Your current exhibition, It is what it is, opened on Friday at Jhana Millers. Can you tell us about the title?

Claudia Kogachi: It is what it is stems from the idea of getting on with things, or a ‘shit happens’ sort of vibe. In the last 6 months, I’ve been thinking a lot about relationships — relationships in the work field, personal relationships, friendships, and my relationship with myself.

‘It is what it is’ is one of those sayings that can be so annoyingly true, but hard to follow. I recently discovered my first white hair which happened to be white at the root and brown by the ends. I stared at this piece of evidence for what seemed like a long time. I was stressed at first, though I realised that stress was probably what caused the hair to go white in the first place. So I thought to myself, ‘It is what it is’.

The exhibition consists of seven paintings, all depicting you, at times with your partner Jordi. Are there any works that have an interesting backstory or source imagery?

The paintings featuring my partner Jordi were a significant decision, as it is the first time I’ve painted anyone outside of my immediate family. This decision also prompted the choice to ditch the blue skin colour for this series. The one with the cockroaches is an image depicting Jordi and I playing backgammon — a game we have picked up in the last 6 months because of the recent lockdown. Backgammon is now a game we play religiously together and seemed suitable to be the scene of play to introduce Jordi into my work.

For me, there's something really compelling about the two small carpet works, roach rug and mosquito rug. They’re about the size of a mini matt that you might keep shoes on, meaning that the image is small enough so that it would be recognisable on the floor, unlike a vast abstract painting. Do you see works like this as functional, or do you imagine them hung on the wall like a painting?

I’d like to think all of the rugs I make can be seen as functional, hence why I underlay them with a backing and overlock the edges for longevity. These rugs are small — much smaller than your average rug — so the idea of having it on the floor cracks me up. I find this funny not in a way that’s protective over the work, but from a practicality aspect. The actual image of the dead cockroach may not be very pleasing to some people, but it’s woven in a rug that takes away from its dirtiness and in my mind makes the dying insect cute?

You've been working with looming techniques, creating pictorial rugs with tufting guns, since the first lockdown in Aotearoa last year; and have stated that the process is reasonably similar to the way you paint, stretching the base material and then drawing on the outlines with crayon and filling the colours in from there. At the same time, the actual machine requires a different type of engagement. Is there a sense of respite when you're working on an exhibition, switching between two quite technically different mediums?

Absolutely! I’m so thrilled that the rugs have had such a positive response, however at the same time I get frustrated when the time taken to make the works isn’t appreciated. The guns themselves weigh roughly 3 kgs, which doesn’t sound like much, but when you’re spending roughly 60+ hours on each large rug the toll this can take on your body is intense. I remember after finishing the last series, my right arm was visibly larger and in more pain than my left. The guns have so much range and have allowed me to experiment with new materials and dimension, however it does restrict movement which can affect the overall work.

Painting acts as a breather from rug tufting. I find when I’m working between the two I engage differently with each process. For example, the rugs require a lot of patience and attention to detail, modes of working I’m not used to when it comes to painting. After making rugs for the past 6 months I noticed I’ve transferred these ways of working over to my paintings.

The frames add something really interesting to the artworks, the panels are set back within a flat, coloured profile. Were they made in your studio?

The frames are all made by Jordi, which was another reason why I decided to include images of him in the paintings. I suppose it’s a homage to his generous work towards my practice. Jordi made each frame by hand and did so while sharing my studio space as I painted.

The idea of working together for this show seemed appropriate as he has witnessed me trying to navigate the conflict and arguments that fuelled the ideas for this series — sometimes he too was a part of the dispute!

Your earlier works were about your (sometimes) sparring relationship with your mother, and the way that intimate family dynamics can become tangled, all-embracing and fraught. Is this something that is still present in your practice?

My mom surprised me by flying down to Wellington for the opening night and was very relieved and pleased to see she wasn’t featured in the works. At this moment in time, my mom and I are getting along well so I find no need to paint us in the same way as I have done in the past. That goes to say I may find myself painting us again one day...

There has also been a shift in the way that you depict your figures. In previous works, they are often incredibly stylised, with blue skin and bold outlines to create form. The clothing is kind of timeless, almost like costumes. Two women boxing in the living room wear slacks and suits, people on a rugby field wear jerseys and shorts. In this new series, the features are a lot finer, you have painted really specific hairstyles that resemble those worn by the actual people you are depicting. Cockroach (diptych) (2021) shows you and your partner Jordi playing backgammon. Your hair is in plaits, something that is quite distinctive about the way you sometimes dress, and you are sitting in jeans and a t-shirt. Is it because the subject matter is perhaps less personal, giving you more freedom to be present in a recognisable way?

This series is the most ‘realistic’ of my work. I’ve decided that the blue figures are reserved for my family, so when Jordi was brought into the mix the use of paint to depict our actual skin tone was discussed. I noticed I paid a lot of attention to detail when it came to paint Jordi and I think that choice is a representation of the adoration I have towards him.

One interesting thing that happened in the process of painting myself was that I couldn’t paint my face until the end. It came to the point where I had all of the work framed and painted, except the figures depicting myself had no face. Painting self-portraits with an anxious or frustrated look was surprisingly hard and confronting, almost like when I found that first white hair.

In the press release for It is what it is, the writer says: “Anxieties, like mosquitos, can keep one up at night.” Is this something you resonate with?

The bugs are code for the people in my life that I’ve wanted to cut out. They are also a metaphor for the stress and anxieties that have come out of conflicts and disputes with certain people in my life. The bugs are obviously causing me grief in the paintings and, like certain relationships, I am trying to get rid or squash them. Some of the attackers are present in scenes where the bugs are in the middle of causing me pain, i.e The one with the bluebottle jellyfish or The one with the head lice. These different stages of annoyance make me think of how sometimes you cannot always catch someone out on their bullshit early on.

“One interesting thing that happened in the process of painting myself was that I couldn't paint my face until the end. It came to the point where I had all of the work framed and painted, except the figures depicting myself had no face. Painting self-portraits with an anxious or frustrated look was surprisingly hard and confronting, almost like when I found that first white hair."

Claudia Kogachi, The one with the sand hoppers, 2021, acrylic on canvas, 140 x 88 cm

Claudia Kogachi, roach rug, 2021, tufted woollen rug, 25 x 25 cm

Claudia Kogachi, The one with the mosquitoes (diptych), 2021, acrylic on canvas, each 80 x 80 cm

Claudia Kogachi, The one with the flies, 2021, acrylic on canvas, 120 x 100 cm

Claudia Kogachi, The one with the blue bottle jellyfish, 2021, acrylic on canvas, 120 x 100 cm

We visited the opening of Kith and Kin on Friday 2 August at Season, featuring brunelle dias, Tony Guo, Levi Kereama, Claudia Kogachi, and Jacqueline Fahey.