die pretty

This text was originally commissioned by Parasite and has been edited by The Art Paper.

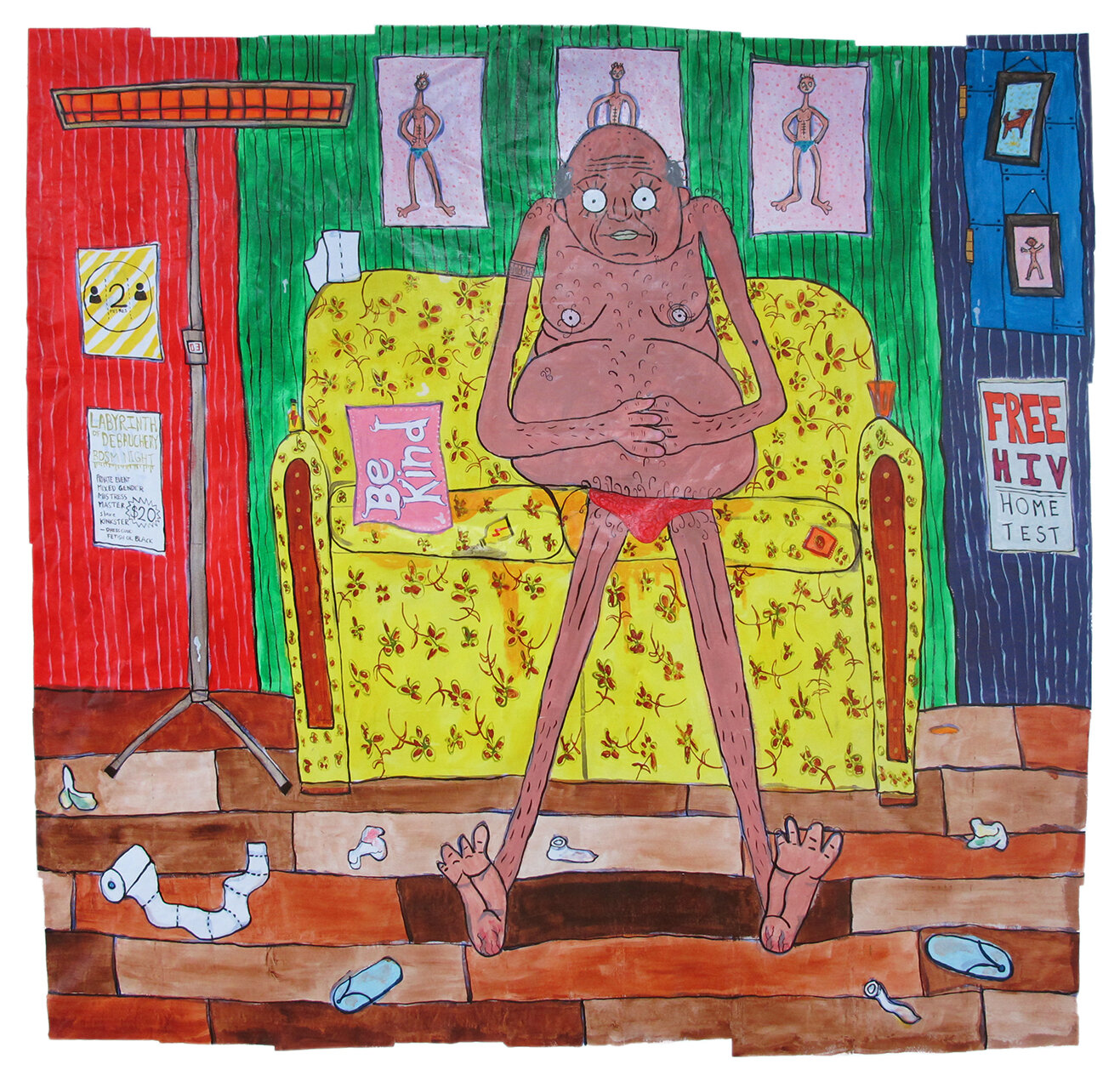

Nayan Patel, Party Boy, 2020, mixed media. Courtesy of the artist and Parasite

One morning, the summer before last, we woke to find someone curled up in the carport next to our bikes. They had let themselves through the gate and taken shelter like a hedgehog under their own sweatshirt.

When the unfamiliar, body-shaped lump came into focus as an actual body, the punch of wariness took a while to fade—even after L. had borrowed the neighbour’s car and given the badly hungover tourist a lift back to the van he’d lost his way to in the night.

The life-size figures featured in Nayan Patel’s Still Life are simply constructed, but nonetheless life-like out of the corner of your eye. They trip a reflex to clock a stranger’s presence.

One, Party Boy, sits on the street by the gallery door, its slumped posture ambiguous between comfortable repose and wasted resignation. Arriving into the alcohol-amplified shuffle of the opening, my double-take registers the possibility that someone’s not OK. Would I step in if they were real? The work lets me off the hook, keeping its place for the next viewer, like a prank prop or decoy.

Starting upstairs, there’s another body behind me, face covered this time by a long black wig. Its title, The Gift, suggests a feint of generosity. A Trojan horse? The obligation bound up in accepting something from someone? Or something about the performance of talent? The trick of the eye could be a deception.

A third and last dummy dangles, as if broken-backed, from a chain umbilicus at the top of the stairs. An acrobat angel or victim of a violent accident, Free Falling twists Party Boy’s pun on suffering and bliss into something more flamboyant. Like a Guy Fawkes guy, it’s an effigy that’s part comic, part horror.

In another respect, these sculptures resemble mannequins: The artist presents a custom-made black cloak in Rain Poncho, shoes peeking out from under the hem. Swing tags are visible in the handbag or desktop conglomerations of the Mind Map collages on the walls; and Sentient Shopper’s carry bag is also fashion retail residue, its Robert-Gober, detached-but-shoe-shod lower leg a kind of jokeshop prêt-à-porter.

Like the selfie-stick and smashed stemware elsewhere in the exhibition—and like the readymade security device Convex Mirror installed realistically at the end of the hang—the three bodies are part of a refracted spectrum of references to seeing yourself and being seen, to surveillance and escape.

They have followed me around since. Their black ensemble shows up in the catering company’s provide-your-own uniform, as well as the designer’s studied, no-look look; minimum wage, zero hour, or paparazzi-ready incognito. The outfit is camouflage for being out in low light, basic Goth; or the rap-listening, anti-Bush-voting masses in the video for Eminem’s “Mosh.” The specific garments, the sweatshirt and pants, are the restaurant owner in black-lettered-on-black Balenciaga on High Street; and the bearded rough sleeper cadging smokes outside the Nelson Street bottle store.

Also, crucially, the hoodie is entangled with the 'racialised other'. It is Trayvon Martin’s, and David Hammons’ In the Hood (1993).

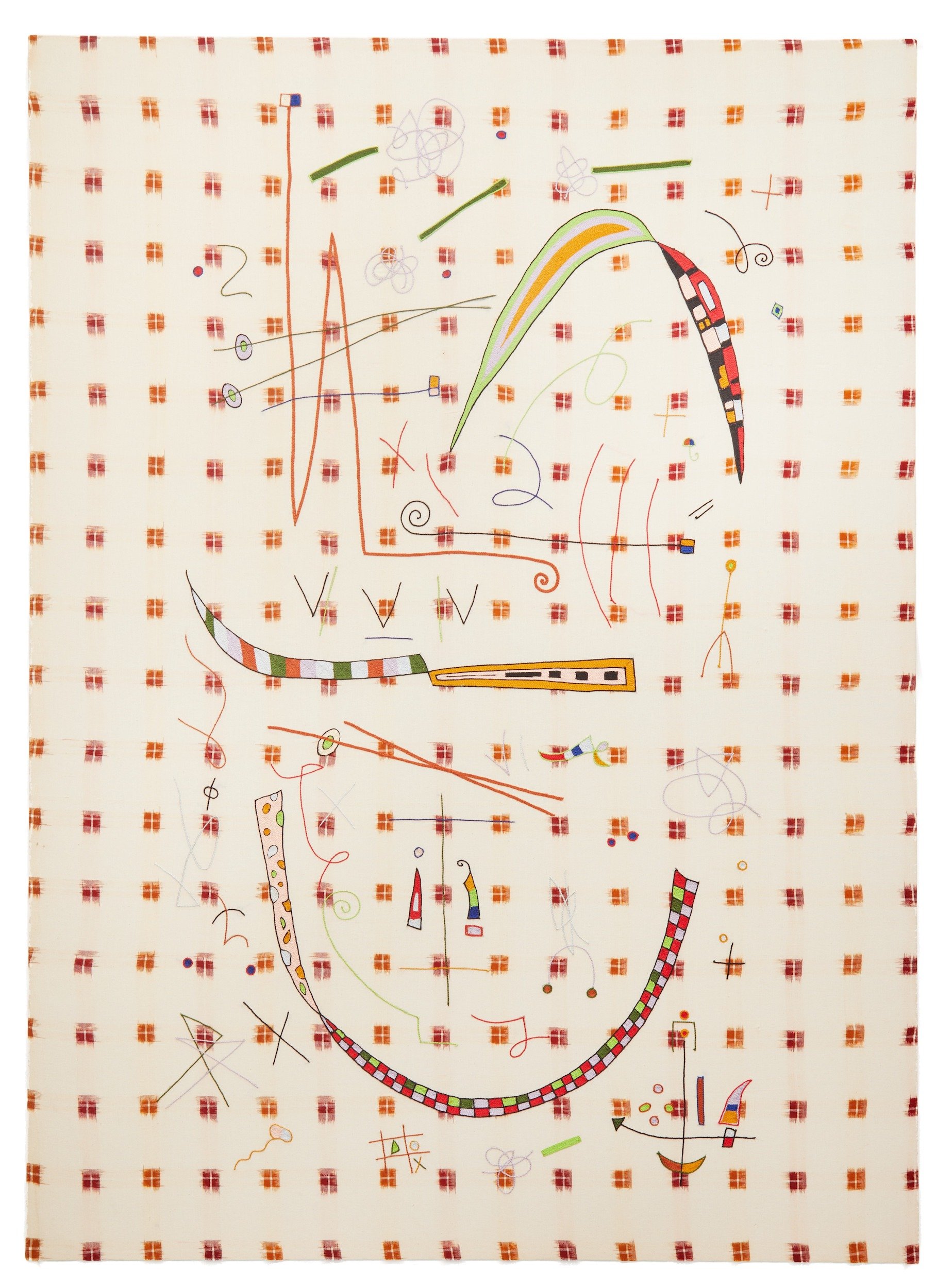

Still Life is not a portrait, but does suggest a social position. Party Boy seems to inhabit a lifestyle forged between extremes, where you can follow haute couture online, and party glamorously with accessories from LookSharp. The Mind Map works are a diary of quick-hit intensities: music videos, vapes, sweets, and the glitter of shattered safety glass. These high-glycemic-index pleasures are constructed with equally temporary fixes: laser printing, sellotape, hot glue, and spray paint.

The connotations of the short-term bring to mind Andy Warhol’s quip about Coke, that the president and the bum are both drinking the same thing: “All the Cokes are the same and all the Cokes are good.” What might be in question is the value in acting towards the longer term.

This is its lasting effect of the work for me, that it holds me with the impasse between a subjective moment and structuring conditions, as unresolvable in the show as it can seem in the world.

Nayan Patel, Free Falling, 2020, mixed media. Courtesy of the artist and Parasite

Nayan Patel, Mind Map, 2020, mixed media. Courtesy of the artist and Parasite

Nayan Patel, Mind Map, 2020, mixed media. Courtesy of the artist and Parasite

Nayan Patel, Rain Poncho, 2020, mixed media. Courtesy of the artist and Parasite

Nayan Patel, Mind Map, 2020, mixed media. Courtesy of the artist and Parasite

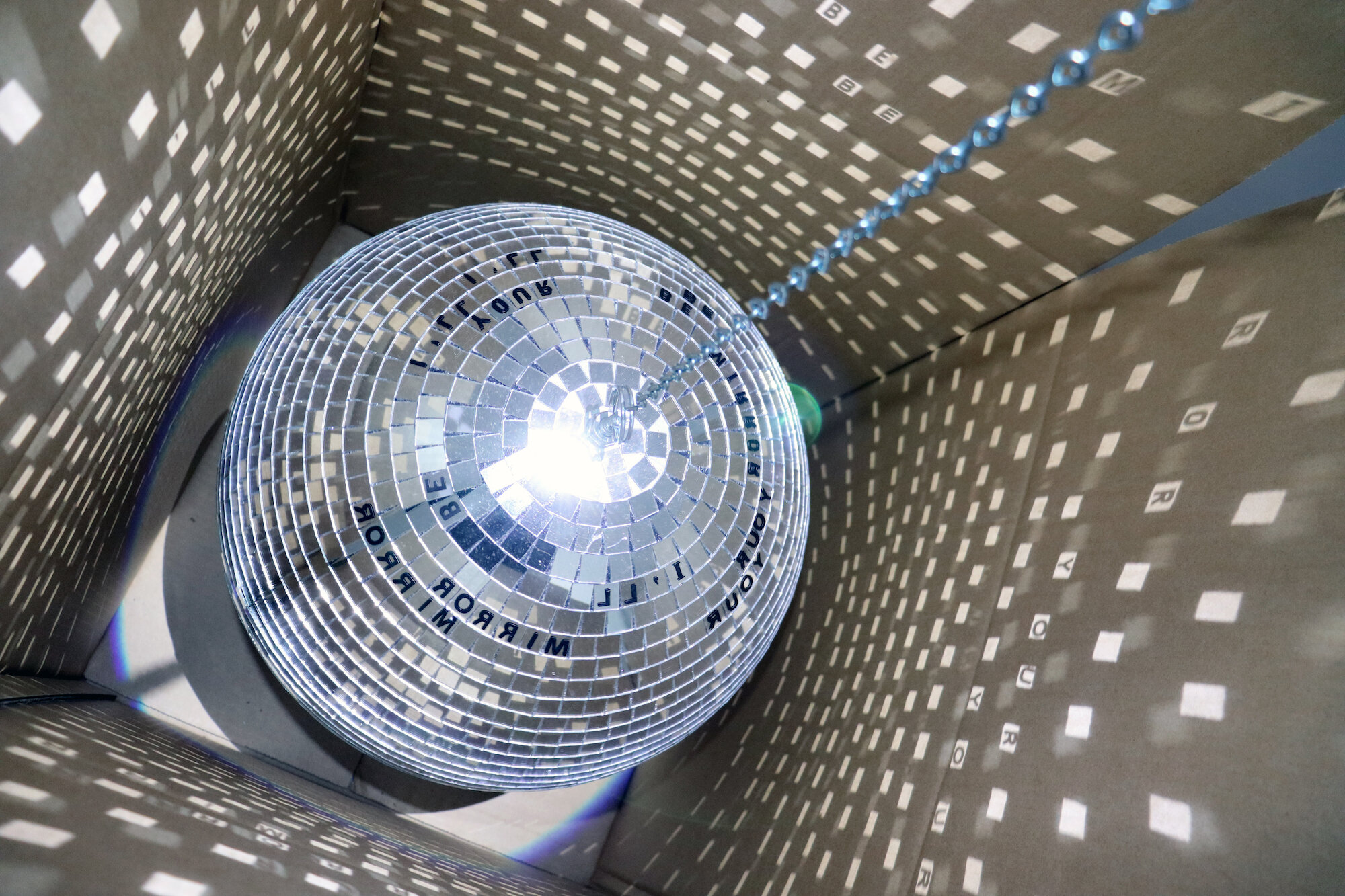

Nayan Patel, Convex Mirror, 2020, mixed media. Courtesy of the artist and Parasite

Nayan Patel, Still Life. Installation view, Parasite, October 2020. Courtesy of the artist and Parasite

Nayan Patel, Free Falling, 2020, mixed media. Courtesy of the artist and Parasite

Nayan Patel, Still Life. Installation view, Parasite, October 2020. Courtesy of the artist and Parasite

Nayan Patel, The Gift, 2020, mixed media. Courtesy of the artist and Parasite

Still Life ran at Parasite, Tāmaki Makaurau, 16 October – 14 November 2020

Julia Craig on Owen Connors’ egg tempera paintings.